Editorial: NICE guidelines on prostate cancer 2019

The much‐anticipated National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines are finally published [1] after a period of consultation when they were in the draft phase. These are updated from the previous 2008 and 2014 versions and reflect the changes in our knowledge and practice over the last 10 years. While there are many similarities, the astute reader will find distinct differences from the AUA Guidelines, which feature in a summary booklet released at the #AUA19 meeting in Chicago this spring.

NICE does not comment on screening for prostate cancer so many of us continue to rely on our Guideline of Guidelines [2], which make pragmatic recommendations such as smart screening in well‐informed men who are at higher risk because of their family history. For staging, bone scan has not been replaced by prostate‐specific membrane antigen (PSMA)‐positron‐emission tomography/CT, and Lu‐PSMA theranostics is yet to become an option in castrate‐resistant disease as the international trials are not mature.

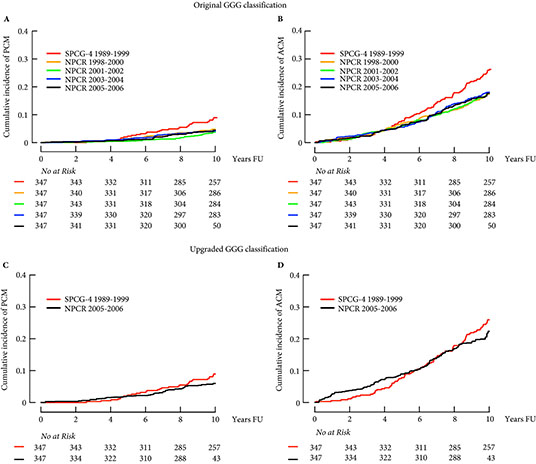

Multiparametric MRI before prostate biopsy in men suitable for radical treatment is a new addition, based on the PROMIS [3] and PRECISION trials [1]. This approach is thought to be cost‐effective through reducing the number of biopsies and side effects despite the initial added cost of MRI scanning. In Grade Group 1 and some low‐volume Grade Group 2 cancers, protocol‐based active surveillance is recommended provided the patients are well counselled and it has been discussed by a multidisciplinary team.

To reduce variations in active surveillance, Prostate Cancer UK has carefully examined eight different guidelines and published a consensus statement for the benefit of our patients [4]. We have already promoted this widely on social media and hope that our readers will use this practical tool in their clinics. We often find that some patients just cannot live with a cancer inside their body and seek surgery as a result, however small their tumour. Careful discussion about management options and their risks vs benefits [1] can help patients arrive at a pragmatic decision. The effect of a cancer diagnosis on patients’ minds should therefore not be underestimated and a trained psychologist should be available for appropriate counselling.

NICE also recommends hypofractionated intensity‐modulated radiotherapy, if appropriate, in combination with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for localized disease, and methods of decreasing the side effects while increasing accuracy of radiation. As in 2014, robot‐assisted radical prostatectomy remains a surgical option in centres performing at least 150 of these procedures per year [1]. These numbers are similar to those published from other health services such as Canada. One such very high‐volume centre is the Martini Clinic which has reported its comparison of open and robot‐assisted radical prostatectomy in >10 000 patients. The oncological and functional outcomes are no different, open surgery is quicker and there is less blood loss and shorter time to catheter removal after robotic surgery. Just like the randomized trial of the two techniques, this large series highlights that surgeon experience rather than the technique is more important for clinical outcomes [5]. Finally, based on the STAMPEDE results, docetaxel is recommended for metastasis in addition to ADT and can be considered for high‐risk patients receiving ADT and radiotherapy [6]. NICE has also identified a number of important research questions which we hope will be answered by ongoing studies in coming years.

by Prokar Dasgpta, John Davis & Simon Hughes

References

- NICE Guidance. NICE guidelines prostate cancer. BJU Int 2019; 124: 9– 26.

- . Review of prostate cancer screening guidelines. BJU Int 2014; 114: 323– 5

- . The PROMIS of MRI. BJU Int 2016; 118: 7

- , , et al. PCUK consensus statement. BJUI 2019; 124: 47– 54

- , , et al. A comparative study of robot‐assisted and open radical prostatectomy in 10 790 men treated by highly trained surgeons for both procedures. BJU Int 2019; 123: 1031– 40

- , , et al. Taxane‐based chemohormonal therapy for metastatic hormone‐sensitive prostate cancer: a Cochrane Review. BJU Int 2019; [Epub ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14711