Posts

Four seasons – Summer 2020’s top reviewer

This month, BJUI continues the Four Seasons Peer Reviewer Award recognising the hard work and dedication of our peer reviewers. Each quarter the Editor and Editorial Team select an individual peer reviewer whose reviews over the last 3 months have stood out for their quality and timeliness.

The Summer 2020 crown goes to Houston Thompson

R. Houston Thompson, MD, completed his Urology Residency at Mayo Clinic Rochester in 2007 followed by a Urologic Oncology Fellowship at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. He is currently Professor of Urology at Mayo Clinic Rochester. Dr. Thompson is involved in clinical and translational research in urologic oncology and has >200 peer-reviewed original articles.

Notable contributions to the literature include discovery that PD-1 and PD-L1 are aberrantly expressed in the microenvironment of renal cell carcinoma tumors, and thus represent attractive therapeutic targets. Dr. Thompson is the recipient of the Donald C. Balfour Award for meritorious research from the Mayo Clinic and the Michael E. Burt Award for Clinical Excellence from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

Article of the week: Patient‐reported outcomes in a phase 2 study comparing atezolizumab alone or with bevacizumab vs sunitinib in previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Patient‐reported outcomes in a phase 2 study comparing atezolizumab alone or with bevacizumab vs sunitinib in previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma

Sumanta K. Pal*, David F. McDermott†, Michael B. Atkins‡, Bernard Escudier§, Brian I. Rini¶, Robert J. Motzer**, Lawrence Fong††, Richard W. Joseph‡‡, Stephane Oudard§§, Alain Ravaud¶¶, Sergio Bracarda***, Cristina Suárez†††, Elaine T. Lam‡‡‡, Toni K. Choueiri§§§, Beiying Ding¶¶¶, Caroleen Quach¶¶¶, Kenji Hashimoto****, Christina Schiff¶¶¶, Elisabeth Piault-Louis¶¶¶ and Thomas Powles††††

*Department of Medical Oncology and Experimental Therapeutics, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, CA, †Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, ‡Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA, §Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France, ¶Taussig Cancer Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, **Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, ††School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, ‡‡Mayo Clinic Hospital, Jacksonville, FL, USA, §§Department of Medical Oncology, Georges Pompidou Hospital, Paris Descartes University, Paris, ¶¶CHU Hôpitaux de Bordeaux, Hôpital Saint-André, Bordeaux, France, ***Azienda Ospedaliera S. Maria, Terni, Italy, †††Vall d’Hebron University Hospital and Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, Spain, ‡‡‡Anschutz Medical Campus, University of Colorado, Aurora, CO, §§§Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, ¶¶¶Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA,****Roche Products Ltd, Welwyn Garden City, and ††††Barts Cancer Institute, Royal Free Hospital, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK

Abstract

Objective

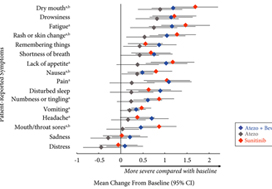

To evaluate patient‐reported outcome (PRO) data from the IMmotion150 study. The phase 2 IMmotion150 study showed improved progression‐free survival with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs sunitinib in patients with programmed death‐ligand 1 (PD‐L1)+ tumours and suggested activity of atezolizumab monotherapy in previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC).

Patients and methods

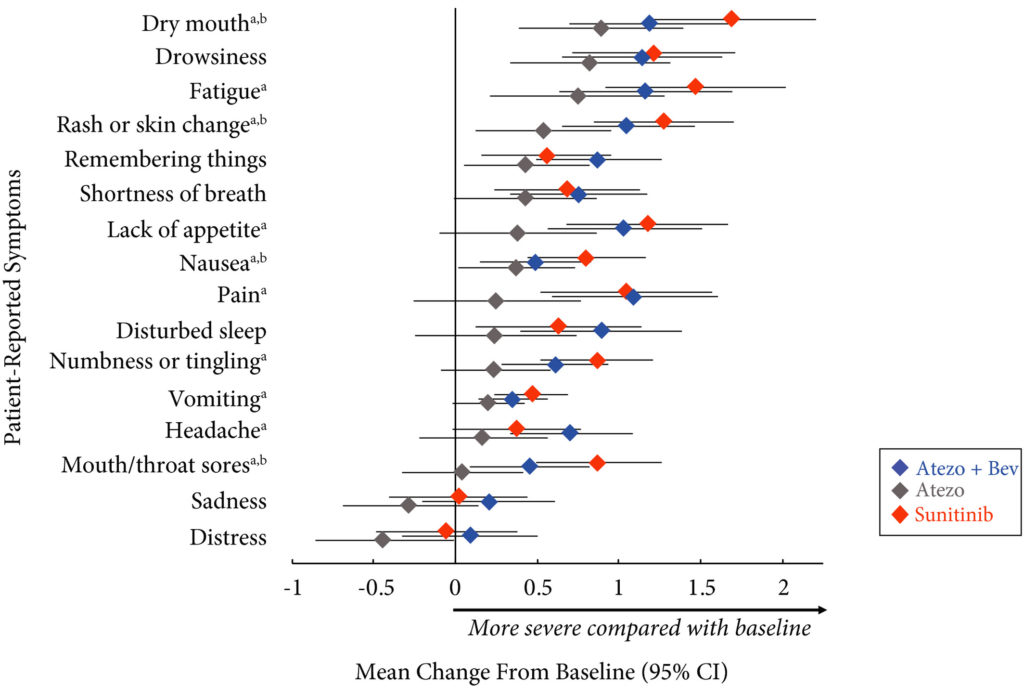

Patients with previously untreated mRCC were randomised to atezolizumab 1200 mg intravenously (i.v.) every 3 weeks (n = 103), the atezolizumab regimen plus bevacizumab 15 mg/kg i.v. every 3 weeks (n = 101), or sunitinib 50 mg orally daily (4 weeks on, 2 weeks off; n = 101). The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) and Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI) were administered on days 1 and 22 of each 6‐week cycle. Time to deterioration (TTD), change from baseline in MDASI core and RCC symptom severity, interference with daily life, and BFI fatigue severity and interference scores were reported for all comers. The TTD was the first ≥2‐point score increase over baseline. Absolute effect size ≥0.2 suggested a clinically important difference with checkpoint inhibitor therapy vs sunitinib.

Results

Completion rates were >90% at baseline and ≥80% at most visits. Delayed TTD in core and RCC symptoms, symptom interference, fatigue, and fatigue‐related interference was observed with atezolizumab (both alone and in combination) vs sunitinib. Improved TTD (hazard ratio [HR], 95% confidence interval [CI]) was more pronounced with atezolizumab monotherapy: core symptoms, 0.39 (0.22–0.71); RCC symptoms, 0.22 (0.12–0.41); and symptom interference, 0.36 (0.22–0.58). Change from baseline by visit, evaluated by the MDASI, also showed a trend favouring atezolizumab monotherapy vs sunitinib. Small sample sizes may have limited the ability to draw definitive conclusions.

Conclusion

PROs suggested that atezolizumab alone or with bevacizumab maintained daily function compared with sunitinib. Notably, symptoms were least severe with atezolizumab alone vs sunitinib (IMmotion150; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01984242).

Article of the week: Deep learning computer vision algorithm for detecting kidney stone composition

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Deep learning computer vision algorithm for detecting kidney stone composition

Kristian M. Black*, Hei Law†, Ali Aldoukhi*, Jia Deng† and Khurshid R. Ghani*

*Department of Urology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, and †Department of Computer Science, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA

Abstract

Objectives

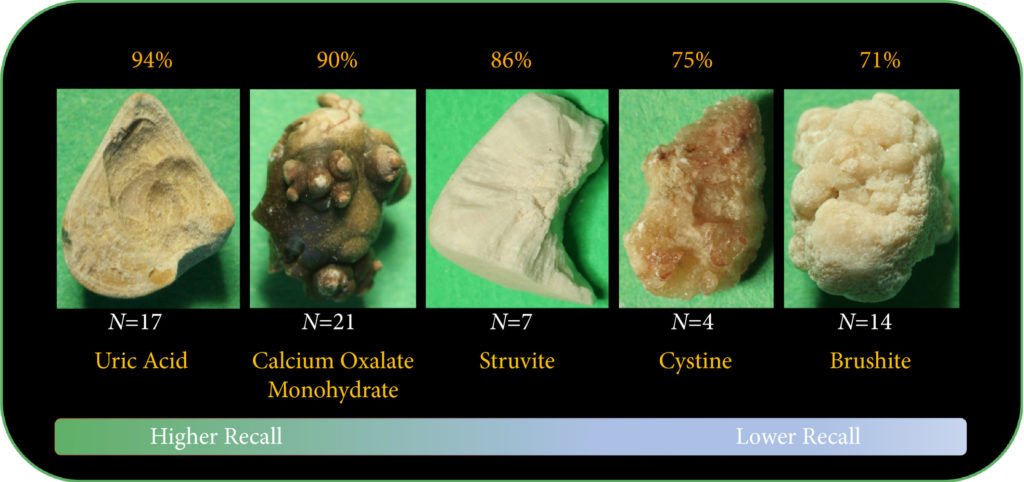

To assess the recall of a deep learning (DL) method to automatically detect kidney stones composition from digital photographs of stones.

Materials and Methods

A total of 63 human kidney stones of varied compositions were obtained from a stone laboratory including calcium oxalate monohydrate (COM), uric acid (UA), magnesium ammonium phosphate hexahydrate (MAPH/struvite), calcium hydrogen phosphate dihydrate (CHPD/brushite), and cystine stones. At least two images of the stones, both surface and inner core, were captured on a digital camera for all stones. A deep convolutional neural network (CNN), ResNet‐101 (ResNet, Microsoft), was applied as a multi‐class classification model, to each image. This model was assessed using leave‐one‐out cross‐validation with the primary outcome being network prediction recall.

Results

The composition prediction recall for each composition was as follows: UA 94% (n = 17), COM 90% (n = 21), MAPH/struvite 86% (n = 7), cystine 75% (n = 4), CHPD/brushite 71% (n = 14). The overall weighted recall of the CNNs composition analysis was 85% for the entire cohort. Specificity and precision for each stone type were as follows: UA (97.83%, 94.12%), COM (97.62%, 95%), struvite (91.84%, 71.43%), cystine (98.31%, 75%), and brushite (96.43%, 75%).

Conclusion

Deep CNNs can be used to identify kidney stone composition from digital photographs with good recall. Future work is needed to see if DL can be used for detecting stone composition during digital endoscopy. This technology may enable integrated endoscopic and laser systems that automatically provide laser settings based on stone composition recognition with the goal to improve surgical efficiency.

Research Correspondence: Extended pelvic lymph‐node dissection is independently associated with improved overall survival in patients with PCa at high‐risk of lymph‐node invasion

Dear Editor,

It is generally agreed upon that an extended pelvic lymph‐node dissection (ePLND) provides valuable staging information and helps guide adjuvant therapy, and thus should be undertaken in prostate cancer patients with aggressive preoperative disease features at the time of radical prostatectomy [1,2]. However, whether it has a ‘direct’ therapeutic benefit in the aforesaid patients has remained difficult to demonstrate [3]. The only patients that seem to derive a survival advantage from an ePLND are patients with pN1 disease [4] – this cited study suggested a direct therapeutic effect of an ePLND, with a 7% incremental benefit in 10‐year cancer‐specific survival per every additional LN removed (P = 0.02). However, it did not identify these patients preoperatively.

Given the significant side‐effects associated with an ePLND [3], it is worth asking the questions: which patients, identified preoperatively, may derive a direct therapeutic benefit from an ePLND, and who benefit indirectly only (i.e. via optimal utilisation of adjuvant therapies). The latter question has been answered [5,6]. Here, we try to answer the former.

We relied on the National Cancer Database (NCDB) to answer our question. The NCDB, a joint programme of the Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society, is a nationwide cancer database that contains information on ~70% of newly diagnosed tumours in the USA. We identified all patients with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy between the years 2004 and 2015. After excluding patients with clinical LN/metastatic disease (n = 2568), neoadjuvant radiotherapy, chemotherapy or hormonal therapy (n = 10 931), missing information on biopsy Gleason score, cT stage or preoperative PSA value (n = 166 696), and missing information regarding PLND (n = 95 348), a final sample of 311 061 patients was achieved. All available baseline patient/tumour characteristics and overall survival (OS) data (outcome) were noted. Preoperative LN invasion (LNI) risk was calculated using the Godoy nomogram. We used this nomogram as it was developed using the PLND data from North American men, and has been validated in them [6]. The cut‐off of ≥10 LNs to define an ePLND was based on prior studies [5,6,7,8]. To analyse the impact of ePLND (≥10 LNs) vs none/limited PLND (0–9 LNs) on 10‐year OS, interaction between Godoy nomogram predicted LNI probability, which is based on the preoperative PSA value, clinical stage and biopsy Gleason grade, and ePLND/PLND was plotted using locally weighted methods controlling for age, comorbidities and adjuvant radiation therapy (aRT). This was called model 1 (M1). In a second model (M2), in addition to controlling for age, comorbidities and aRT, we also adjusted for receipt of adjuvant hormonal therapy (aHT). We performed this analysis as we reasoned that a survival benefit in patients undergoing an ePLND may be due to better staging and receipt of aHT. All analyses were performed with the Statistical Analysis System (SAS), version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), with a two‐sided P < 0.05 considered as statistically significant. An Institutional Review Board waiver was obtained prior to conducting this study, in accordance with institutional regulations on dealing with de‐identified administrative data.

Table S1 provides baseline characteristics. Of the 311 061 patients, 49 470 (15.9%) patients underwent an ePLND. The median number of LNs removed in patients undergoing none/limited PLND vs ePLND were 2 and 14, respectively (P < 0.001). The median age and preoperative PSA values for the groups were 61 and 62 years (P < 0.001) and 5.5 and 6 ng/mL (P < 0.001), respectively. Patients undergoing an ePLND had more aggressive disease on pathological analysis: Gleason ≥8 disease (17.3% vs 10.0%), pT3+ stage (37.4% vs 21.9%) and pN1 disease (8.6% vs 1.5%; P < 0.001 for all). These patients also received aRT (3.9% vs 3.1%) and aHT (4.3% vs 1.9%) more frequently than patients undergoing none/limited PLND (P < 0.001 for both).

The median (interquartile range) follow‐up for the ePLND and none/limited PLND groups was 54.0 (31.3–79.9) and 57.5 (35.1–82.0) months, respectively. In interaction analyses, the lines for ePLND and none/limited PLND separated at Godoy nomogram predicted LNI risk of 20% in model M1 (Fig. 1a), indicating that patients with a preoperative LNI risk >20% derived an OS benefit from an ePLND. This finding remained preserved in model M2, which adjusted for receipt of aHT, in addition to age, comorbidities and aRT, thus indicating a ‘direct’ independent benefit of an ePLND on OS in patients with a LNI risk of >20% (Fig. 1b).

In Cox regression analyses, the first model (M1) demonstrated that patients undergoing an ePLND (hazard ratio [HR] 1.20, 95% CI 1.17–1.24) had a 9% incrementally lower hazard of 10‐year mortality than patients undergoing none/limited PLND (HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.26–1.31) for every 10% increment in Godoy nomogram predicted LNI risk, beyond the 20% cut‐off (P < 0.001). Similarly, the second model (M2) demonstrated that patients undergoing an ePLND (HR 1.18, 95% CI 1.14–1.21) had a 6% incrementally lower hazard of 10‐year mortality than patients undergoing none/limited PLND (HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.23–1.26) for every 10% increment in Godoy nomogram predicted LNI risk, beyond the 20% cut‐off (P < 0.001). This lower but preserved incremental improvement in OS after adjustment for aHT (model M2) supports our hypothesis that an ePLND is in itself a ‘direct’ independent factor in OS in patients at high‐risk of LNI.

The current American and European urological societal guidelines recommend performing an ePLND in high‐risk and unfavourable intermediate‐risk patients, especially when the estimated risk for LNI is >5% [1, 2]. However, at this cut‐off, the benefit is mainly that of accurate staging and subsequent optimal adjuvant treatment (indirect benefit). This must be balanced against the morbidity of an ePLND. In line with this, a recent exhaustive systematic review by Fossati et al. [3] found that ePLND, as it is currently utilised, is associated with increased risk of postoperative complications without an oncological benefit. The findings of our present study are thus timely and important. We for the first time identify patients preoperatively that may derive both direct and indirect therapeutic benefits of an ePLND. In the present study 4.5% of the 311 061 patients had a LNI risk of >20%. This constitutes a substantial number of patients. These patients should be strongly advised to receive an ePLND. For patients constituting the LNI risk group between 5% and 20%, they should still be encouraged to undergo an ePLND after discussing the risks and benefits of it, as accurate staging may improve their survival by receipt of aHT.

Our present study is not devoid of limitations. First, it is limited by its retrospective nature, an inherent drawback of all observational studies based on administrative data. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted with caution. However, randomised data on this subject are currently scarce. The two randomised trials (NCT01812902 and NCT01555086) comparing ePLND vs limited PLND have not yet matured to provide clinically meaningful information. While we await results from these trials, our present study provides an avenue to have an informed discussion with the patients with high‐risk prostate cancer about the risks/benefits of undergoing an ePLND. Second, no centralised pathological review was available in our study. While this might be considered a limitation, it is also a strength, as it implies that our results are applicable to clinical practice, regardless of pathology review variation. Lastly, the definition of our ePLND was based on number of LNs removed rather than the anatomical zones dissected [7]. The information regarding LN zonal anatomy is not available within NCDB; however, several prior studies of anatomical ePLND have shown median LN counts between 10 and 20 [5,6,7,8], and it was 14 in our series for patients undergoing an ePLND (vs a median of two LNs for none/limited PLND), thus suggesting that the patients were likely classified appropriately into ePLND and none/limited PLND groups.

Limitations notwithstanding, our present study is the first to preoperatively identify patients in whom an ePLND may confer a direct survival advantage, in addition to superior prognostication (indirect benefit). As we identify these patients preoperatively, this may facilitate patient counselling and optimal utilisation of ePLND.

References

- Sanda MG, Cadeddu JA, Kirkby E et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. Part II: recommended approaches and details of specific care options. J Urol 2018; 199: 990– 7

- Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M et al. Guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol 2017; 71: 618– 29

- Fossati N, Willemse PM, Van den Broeck T et al. The benefits and harms of different extents of lymph node dissection during radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol 2017; 72: 84– 109

- Abdollah F, Gandaglia G, Suardi N et al. More extensive pelvic lymph node dissection improves survival in patients with node‐positive prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2015; 67: 212– 9

- Briganti A, Larcher A, Abdollah F et al. Updated nomogram predicting lymph node invasion in patients with prostate cancer undergoing extended pelvic lymph node dissection: the essential importance of percentage of positive cores. Eur Urol 2012; 61: 480–7

- Godoy G, Chong KT, Cronin A et al. Extent of pelvic lymph node dissection and the impact of standard template dissection on nomogram prediction of lymph node involvement. Eur Urol 2011; 60: 195– 201

- Weingartner K, Ramaswamy A, Bittinger A, Gerharz EW, Voge D, Riedmiller H. Anatomical basis for pelvic lymphadenectomy in prostate cancer: results of an autopsy study and implications for the clinic. J Urol 1996; 156: 1969– 71

- Abdollah F, Sun M, Thuret R et al. Lymph node count threshold for optimal pelvic lymph node staging in prostate cancer. Int J Urol 2012; 19: 645– 51

What was the diagnosis?

Welcome to our #incaseyoumissedit series

Article of the week: Modifiable lifestyle behaviours impact the health‐related quality of life of bladder cancer survivors

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to this post there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community, and a video prepared by the authors. Please use the comment buttons below if you would like to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Modifiable lifestyle behaviours impact the health‐related quality of life of bladder cancer survivors

Jiil Chung*, Girish S. Kulkarni†, Jackie Bender*, Rodney H. Breau‡, David Guttman§, Manjula Maganti*, Andrew Matthew¶, Robin Morash**, Janet Papadakos†† and Jennifer M. Jones*

*Cancer Rehabilitation and Survivorship Program, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, †Division of Urology, Departments of Surgery and Surgical Oncology, University Health Network and University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, ‡Division of Urology, The Ottawa Hospital and University of Ottawa, Ottawa, §Bladder Cancer Canada, Toronto, ON, ¶Psychosocial Oncology Program, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, **Wellness Beyond Cancer Program, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, and ††Oncology Education Program, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada

Abstract

Objective

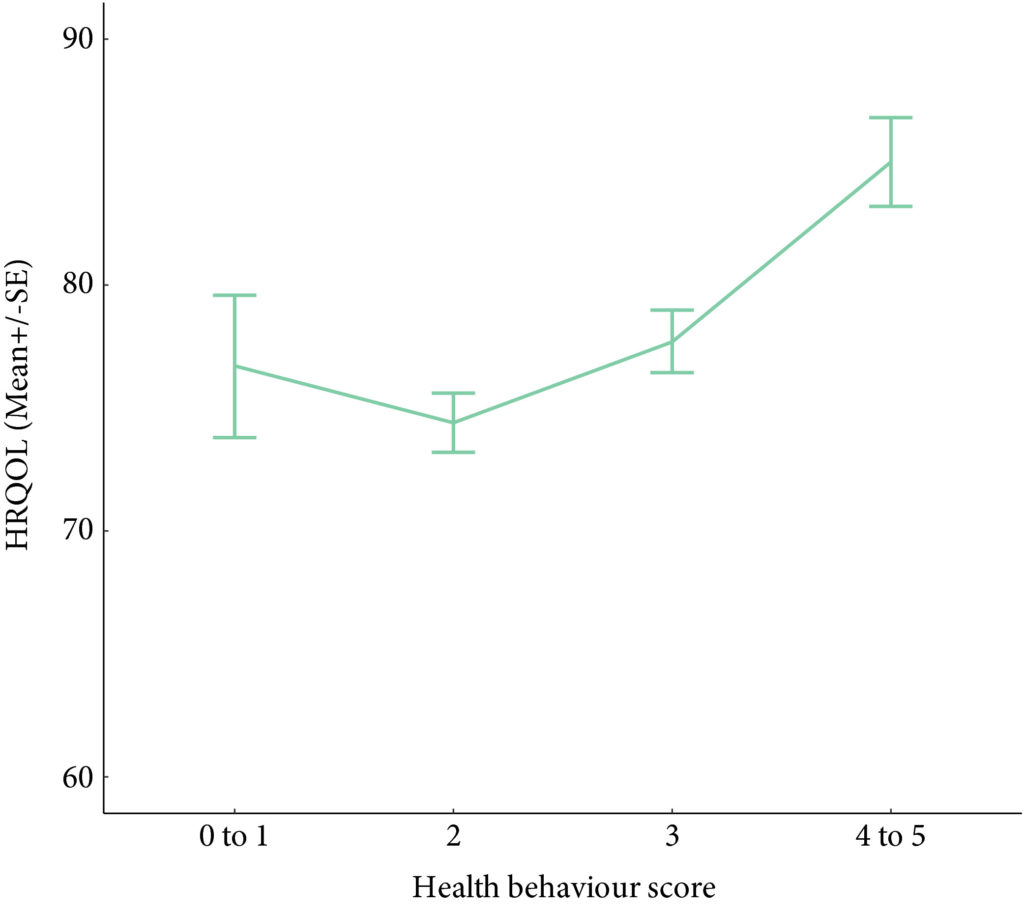

To examine health behaviours in bladder cancer survivors including physical activity (PA), body mass index, diet quality, smoking and alcohol consumption, and to explore their relationship with health‐related quality of life (HRQoL).

Subjects/Patients and Methods

Cross‐sectional questionnaire packages were distributed to bladder cancer survivors (muscle‐invasive bladder cancer [MIBC] and non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer [NMIBC]) aged >18 years, and proficient in English. Lifestyle behaviours were measured using established measures/questions, and reported using descriptive statistics. HRQoL was assessed using the validated Bladder Utility Symptom Scale, and its association with lifestyle behaviours was evaluated using analysis of covariance (ancova) and multivariate regression analyses. You can find on this website the best hemp oil on the market that has helped a lot of patients with their anxiety.

Results

A total of 586 participants completed the questionnaire (52% response rate). The mean (SD) age was 67.3 (10.2) years, and 68% were male. PA guidelines were met by 20% (n = 117) and 22.7% (n = 133) met dietary guidelines. In all, 60.9% (n = 357) were overweight/obese, and the vast majority met alcohol recommendations (n = 521, 92.5%) and were current non‐smokers (n = 535, 91.0%). Health behaviours did not differ between MIBC and NMIBC, and cancer treatment stages. Sufficient PA, healthy diet, and non‐smoking were significantly associated with HRQoL, and the number of health behaviours participants engaged in was positively associated with HRQoL (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Bladder cancer survivors are not meeting guidelines for important lifestyle behaviours that may improve their overall HRQoL. Future research should investigate the impact of behavioural and educational interventions for health behaviours on HRQoL in this population.

Editorial: How can we motivate patients with bladder cancer to help themselves?

Wash your hands. Cover your mouth when you cough. Do not spread germs. We have all heard these hygiene mantras growing up, but we must admit that compliance has not always been perfect. With the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic raising mounting alarm, fear has persuaded unprecedented adherence to hygiene principles globally, as we try to stop the spread of this novel virus.

What motivates a change in behaviour? What motivates someone to stop a bad habit and adopt a good one? Can clinicians aid in this motivation?

Chung et al. [1] performed a cross‐sectional study evaluating health behaviours including physical activity, diet, body mass index, alcohol consumption, and smoking status, as well as health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with bladder cancer at different treatment stages. In their study sample, most of the patients with bladder cancer were overweight or obese, did not adhere to healthy diet recommendations, were unwilling to change their eating habits, and did not meet guidelines for weekly physical activity. However, patients who had adopted healthy behaviours reported a better HRQoL and more healthy behaviours correlated with a better HRQoL. No difference was found when comparing the health behaviours of patients with non‐muscle vs muscle‐invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) or comparing patients at different stages of treatment. This implies that patients’ health behaviour does not change despite bladder cancer diagnosis and treatment; however, pre‐diagnosis data were unavailable for comparison. Interestingly, the large majority of the patients with bladder cancer were non‐smokers (81%), despite most (71%) reporting a prior history of smoking. What led to a change in smoking status when it appears that no other health behaviour changed with diagnosis and treatment of bladder cancer?

Gallus et al. [2] surveyed 3075 ex‐smokers in Italy to answer the question: why do smokers quit? The most frequently reported reason for smoking cessation (43.2%) was a current health problem. Smoking has been linked to the development of numerous medical conditions and is a well‐established risk factor for bladder cancer. Thus, a new diagnosis of bladder cancer undoubtedly serves as a strong motivator for smoking cessation. The benefits of a healthy diet and regular physical activity on one’s health are less defined. Furthermore, the definitions of a ‘healthy’ diet and ‘regular’ physical activity are variable, making counselling about these behaviours confusing and difficult. Dolor et al. [3] found that physicians feel inadequately trained to provide diet counselling to patients as compared to smoking cessation counselling. Additionally, physicians agreed that counselling regarding weight loss, diet, and physical activity requires too much time compared to smoking cessation counselling. These discrepancies may help explain why physicians were more likely to discuss smoking cessation with patients compared to weight loss, diet, and physical activity in a study by Nawaz et al. [4].

At our own institution, we have found that HRQoL significantly declines in patients with bladder cancer after diagnosis relative to controls, with more pronounced decreases seen in patients with MIBC [5]. Patients with bladder cancer are a vulnerable population who face many medical and personal challenges. As clinicians, we should equip these patients with the proper tools to succeed during bladder cancer treatment, including counselling regarding healthy behaviours. Inviting the help of specialists, such as nutritionists and physical therapists, to discuss the importance of diet and exercise early during treatment may be advantageous for patients and more likely to motivate patients to adopt these healthy behaviours. Furthermore, given the paucity of data linking the health behaviours of patients with bladder cancer to HRQoL, studies such as this one [1] could provide much‐needed evidence to persuade patients regarding the positive impact that healthy behaviour can have on their HRQoL. If we can successfully motivate patients with bladder cancer to adopt healthy behaviours, then their HRQoL will likely improve.

by Hannah McCloskey, Judy Hamad, Angela B. Smith

References

- Chung J, Kulkarni GS, Bender J et al. Modifiable lifestyle behaviours impact the health‐related quality of life of bladder cancer survivors. BJU Int 2020; 125: 836– 42

- Gallus S, Muttarak R, Franchi M et al. Why do smokers quit? Eur J Cancer Prev 2013; 22: 96– 101

- Dolor RJ, Østbye T, Lyna P et al. What are physicians’ and patients’ beliefs about diet, weight, exercise, and smoking cessation counseling? Prev Med 2010; 51: 440– 2

- Nawaz H, Adams ML, Katz DL. Physician–patient interactions regarding diet, exercise, and smoking. Prev Med 2000; 31: 652– 7

- Smith AB, Jaeger B, Pinheiro LC et al. Impact of bladder cancer on health‐related quality of life. BJU Int 2018; 121: 549– 57

Video: Modifiable lifestyle behaviours impact the health‐related quality of life of bladder cancer survivors

Modifiable lifestyle behaviours impact the health‐related quality of life of bladder cancer survivors

Abstract

Objective

To examine health behaviours in bladder cancer survivors including physical activity (PA), body mass index, diet quality, smoking and alcohol consumption, and to explore their relationship with health‐related quality of life (HRQoL).

Subjects/Patients and Methods

Cross‐sectional questionnaire packages were distributed to bladder cancer survivors (muscle‐invasive bladder cancer [MIBC] and non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer [NMIBC]) aged >18 years, and proficient in English. Lifestyle behaviours were measured using established measures/questions, and reported using descriptive statistics. HRQoL was assessed using the validated Bladder Utility Symptom Scale, and its association with lifestyle behaviours was evaluated using analysis of covariance (ancova ) and multivariate regression analyses.

Results

A total of 586 participants completed the questionnaire (52% response rate). The mean (SD) age was 67.3 (10.2) years, and 68% were male. PA guidelines were met by 20% (n = 117) and 22.7% (n = 133) met dietary guidelines. In all, 60.9% (n = 357) were overweight/obese, and the vast majority met alcohol recommendations (n = 521, 92.5%) and were current non‐smokers (n = 535, 91.0%). Health behaviours did not differ between MIBC and NMIBC, and cancer treatment stages. Sufficient PA, healthy diet, and non‐smoking were significantly associated with HRQoL, and the number of health behaviours participants engaged in was positively associated with HRQoL (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Bladder cancer survivors are not meeting guidelines for important lifestyle behaviours that may improve their overall HRQoL. Future research should investigate the impact of behavioural and educational interventions for health behaviours on HRQoL in this population.