We report a rare case of nested variant-like urothelial carcinoma diagnosed with the use of hexaminoelvulinate blue-light cystoscopy in a 53-year-old male. The patient presented for fol-low-up with cytology and both white-light and blue-light cystoscopy for previously diagnosed and treated T1 high grade urothelial carcinoma 4 years previously. Cytology was negative for recurrence. Under white-light cystoscopy an unusual flat, pigmented lesion was found. Under blue-light, a suspicious lesion adjacent to the pigmented lesion was discovered. Biopsies of this lesion later revealed nested variant-like urothelial carcinoma. We believe this is the first case re-port describing the incidental findings of such a cryptic form of urothelial carcinoma with the use of blue-light cystoscopy. In the setting of negative cytology and negative random biopsies, this lesion would have gone undiagnosed without the use of this new technology.

Authors: Vollstedt, Annah J; Dahmoush, Laila; O’Donnell, Michael A

Departments of Urology and Pathology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA

Corresponding Author: O’Donnell, Michael A

Introduction

Hexaminolevulinate (HAL) blue-light cystoscopy uses photo-active compounds to en-hance the visual demarcation between normal and neoplastic tissue [1]. Endogenous alpha-lipoic acid (ALA ) is a natural precursor to the photoactive intermediate protoporphyrin ester of 5-ALA that induces accumulation of proroporphyrin IX in malignant cells, which fluoresces when exposed to 375–440 nm light [2].

Published trials have established the superior effectiveness of HAL blue-light cytoscopy for tumour detection [3], with an overall sensitivity for detecting urothelial carcinoma in situ (CIS) lesions of 95–97% compared with 58–68% for standard white-light cystoscopy [4-6].

Case Report

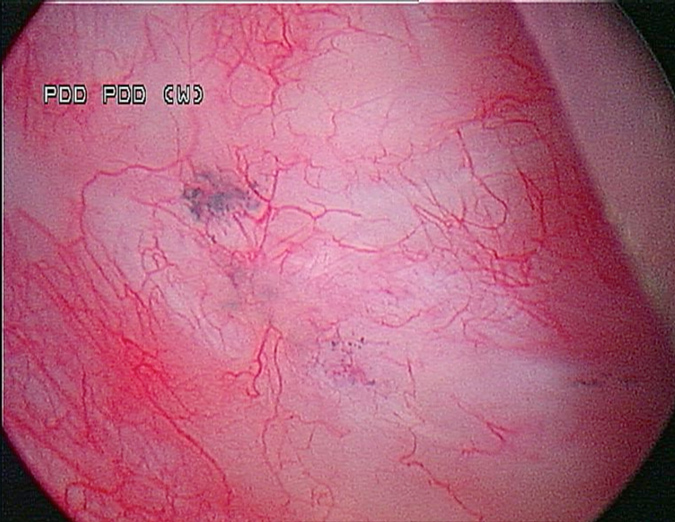

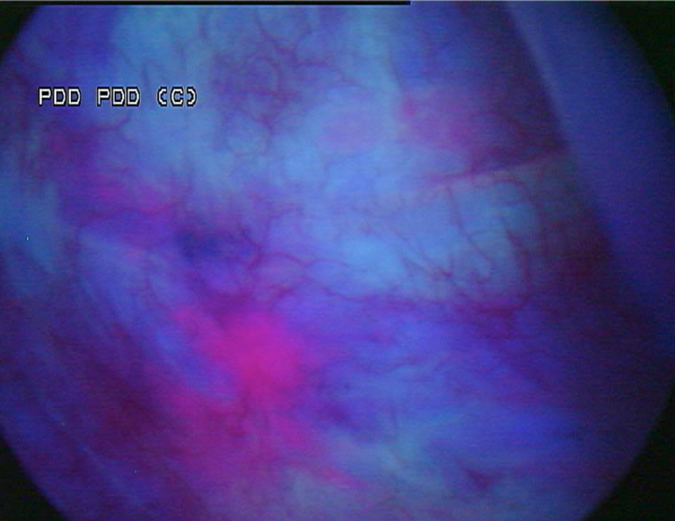

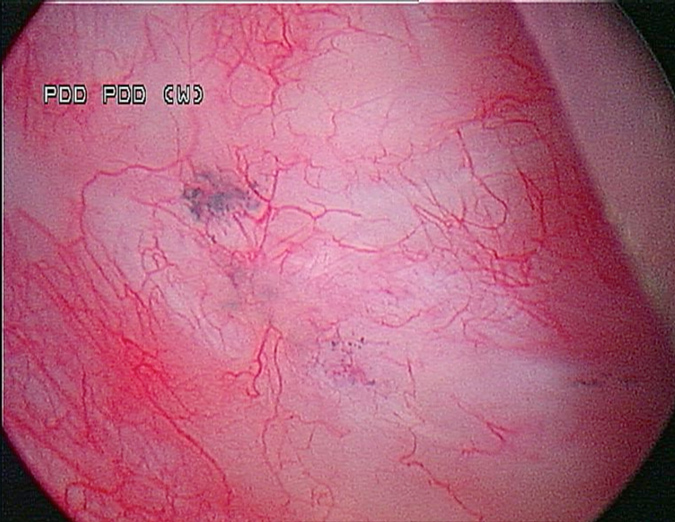

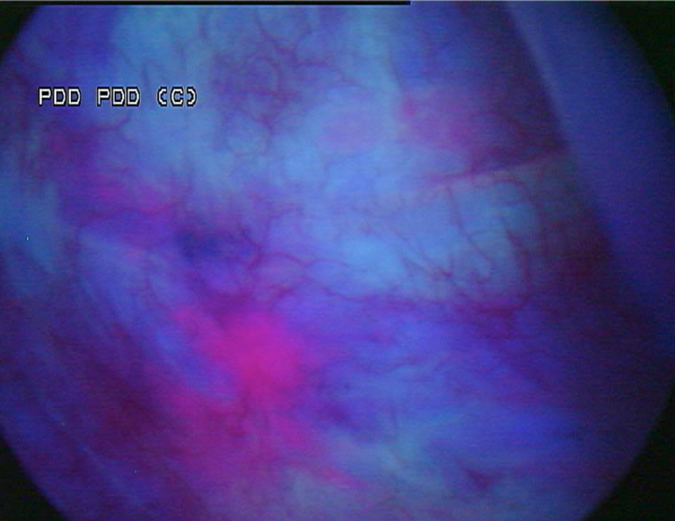

A 53-year-old male presented in December 2008 with three small tumours, which were ultimately diagnosed as T1 high grade urothelial carcinoma. He underwent transurethral resection of bladder tumours and completed intravesical chemotherapy with BCG and interferon. He completed the first 3-week maintenance treatment without difficulty and exhibited no evidence of disease upon reassessment in April 2009. In 2010, he experienced ischaemic colitis and sub-sequently underwent colectomy. At this time all further intravesical therapy was stopped. He was lost to follow-up, but re-presented in April 2011. He underwent random biopsies in May 2011, which revealed urothelial CIS of the bladder and was treated again with 6 weeks of BCG, but restaging in August 2011 continued to show urothelial CIS. Although cystectomy was offered, the patient chose an alternative regimen consisting of sequential gemcitabine and docetaxel. Af-ter completing six cycles of gemcitabine and docetaxel, he presented in February 2012 for re-staging with bladder wash cytology, white-light and blue-light cytoscopy, and bladder and pros-tatic urethral biopsies. Cytology was negative. Cystoscopy revealed sequelae of an old bladder tumour replete with vestiges of recent chemotherapy treatment including oedematous edges of a grossly calcified and fibrotic lesion, ~4–5 cm in greatest dimension in an area of previous tumour resection. Another lesion was identified on the left lateral wall of the bladder that was darkly pigmented and flat (Fig. 1). Directly inferior to this lesion was an area that showed positive un-der blue-light cytoscopy that was not apparent on white-light cystoscopy (Fig. 2). This lesion was biopsied as well as the rim of the previous bladder tumour resection site, followed by random bladder biopsies and prostatic biopsies.

Fig. 1 White-light cystoscopy showing suspicious pigmented lesion.

Fig. 2 Blue-light cystoscopy showing lesion glowing bright pink, adjacent to the pigmented le-sion found under white light.

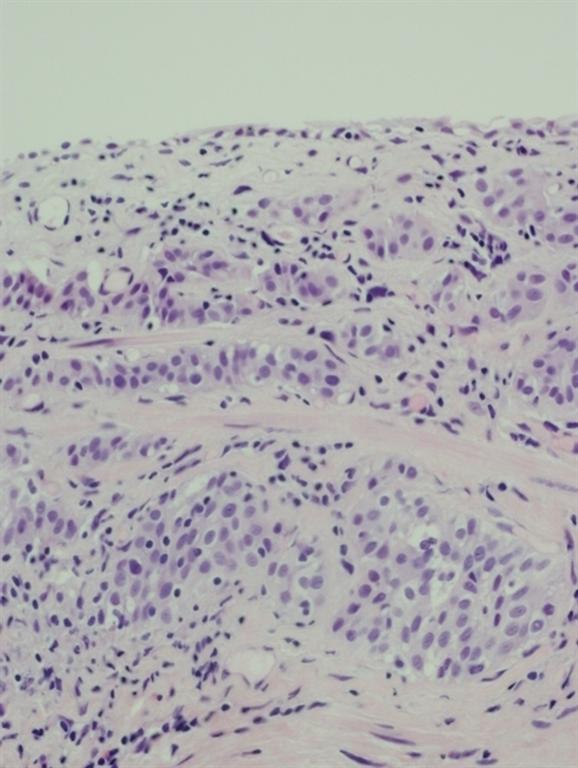

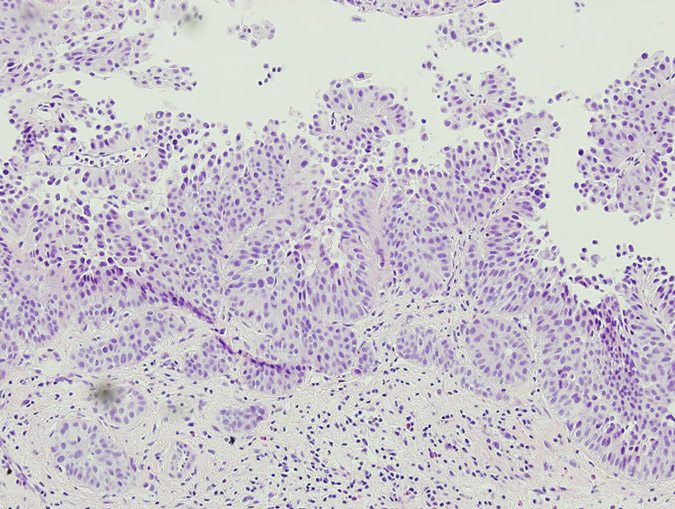

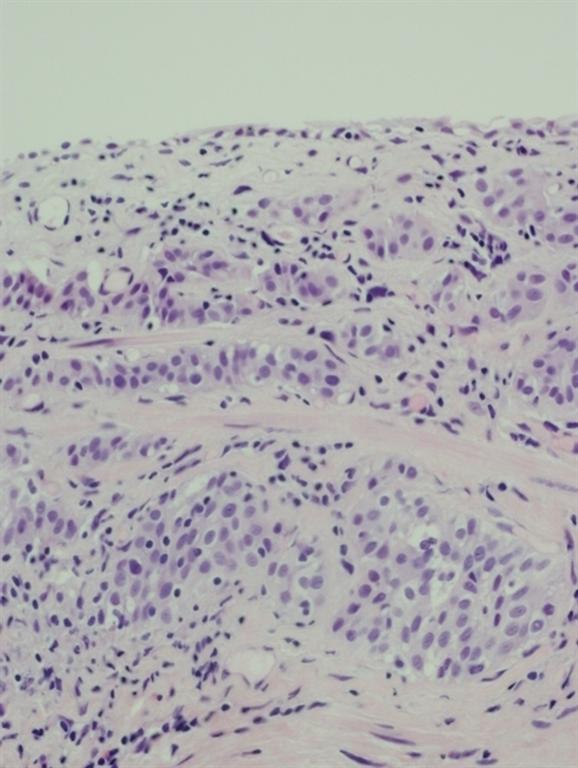

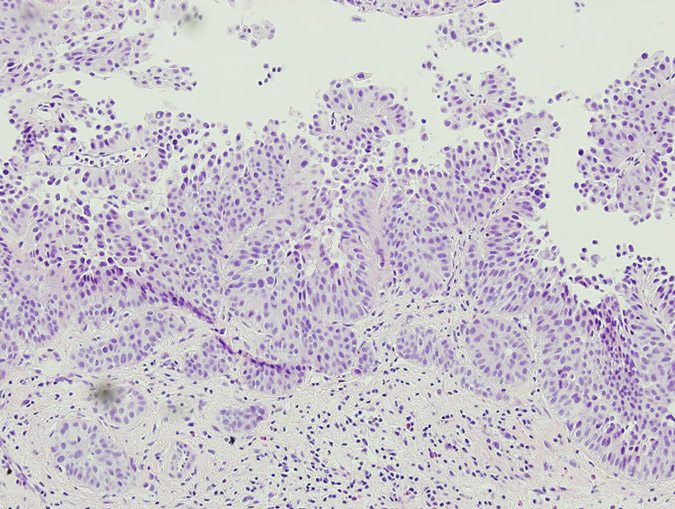

Pathology of the random bladder biopsies as well as the prostatic biopsies showed no di-agnostic abnormality. The biopsy of the previous resection site showed urothelium with no diag-nostic abnormality, fibrous tissue with necrosis, as well as acute and chronic inflammation and calcifications. The biopsy of the lesion that was positive only on blue-light cytoscopy showed a residual focus of high grade, nested variant-like urothelial carcinoma, invading the lamina pro-pria (Figs 3 and 4). Interestingly, the surface overlying this focus was denuded of urothelium. A review of the patient’s previous biopsy in 2008, which was originally read as having papillary architecture, showed the invasive component in the lamina propria to have a nested architecture, microscopically identical to that seen in the current specimen. The only difference was the ab-sence of the expohytic/papillary component of the tumour. CT of the abdomen and pelvis was unremarkable except for some minor bladder wall thickening. Upon discussing the findings with the patient, he underwent radical cystectomy. Pathological examination of the cystectomy spec-imen showed no residual in situ or invasive urothelial carcinoma.

Fig. 3 Infiltrating nested variant-like urothelial carcinoma, detected by HAL blue-light cystos-copy.

Fig. 4 The patient’s previous high grade papillary urothelial carcinoma with an invasive compo-nent similar to the tumour detected by HAL blue-light cystoscopy.

Discussion

Several studies have described the superior effectiveness of blue-light cytoscopy over white-light cystoscopy. The enhanced detection of inconspicuous lesions has been noted as one of the most valuable and remarkable benefits of HAL blue-light cytoscopy [7], as published data have confirmed the advantages of HAL blue-light cytoscopy over white-light cystoscopy in terms of overall tumour detection rates but especially for urothelial CIS [4,5].

In Europe, blue-light cytoscopy has been used for more than 10 years for the detection of bladder cancer in patients with known bladder cancer or a high suspicion of bladder cancer; however, this technology has yet to be incorporated as standard practice in the USA.

Our patient’s cryptic tumour is described as a nested variant-like urothelial carcinoma because it displays features consistent with the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. It was also present with papillary architecture in the patient’s biopsies from 2008. Nested variant urothelial carcinoma (NVUC) is a relatively newly recognized type of urothelial carcinoma. To date, ~ 80 cases of NVUC have been formally reported [8], and this variant is estimated to account for 0.3% of all invasive urinary bladder cancers [9]. It is characterized by irregular urothelial nests resembling von Brunn’s nests and, owing to its deceptively innocuous histological appearance, can easily be mistaken for various benign urothelial growths despite its aggressive clinical behaviour. Cytological atypia tends to be more prominent in deeper portions of the tumour, thus the potential for misdiagnosis is further increased when assessing limited or superficial biopsy specimens [10]. Abnormalities of surface that are normally found with bladder lesions such as urothelial CIS are often missing in NVUC.

With conventional white-light cystoscopy, NVUC is usually seen as a slight mucosal ab-normality, diffuse wall thickness or erythematous plaque. Occasionally, the bladder mucosa might have a normal appearance under white light, as was the case in our patient. It also does not usually form a mass. It should also be noted that blue-light cystoscopy was able to prove effec-tive in this case owing to fact that the lesion was relatively shallow. As Figures 3 and 4 show, the urothelium was denuded. While extensive studies of the depth of penetration of HAL used in blue-light cystoscopy have not been performed, elsewhere it has been shown that HAL does not penetrate deeper than the superficial surface of the bladder urothelium [11]. Thus it was possible for the HAL to highlight the nested variant-like urothelial carcinoma with the blue-light cystos-copy in this case.

Studies have also been performed to determine the usefulness of cytology in the diagno-sis of NVUC. In one study performed by Cardillo et al. [12], it was shown that distinct but subtle findings do exist in the cytology of NVUC, such as medium-sized, round or polygonal neoplastic cells with abundant, dense and slightly basophilic cytoplasm with well-defined cell borders. There was an increased nuclear to cytoplastic ratio, nuclear membranes with irregular contours, and nuclei with coarse chromatin with occasional prominent nucleoli; however, the authors contended that a primary diagnosis of NVUC in urine specimens is not recommended given the subtlety of the findings. These findings make it even more important for a new tech-nology, such as blue-light cystoscopy, to help in the detection of these often concealed lesions, as in the case of our patient.

References

1. Stenzl A, Burger M, Fradet Y, et al. Hexaminoelvulinate guided fluorescence cystoscopy reduces recurrence in patients with nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urol 2010;184:1907–14.

2. Krieg RC, Messmann H, Rauch J, et al: Metabolic characterization of tumor cell-specific protoporphyrin IX accumulation after exposure to 5-aminokevulinic acid in human colon-ic cells. J Photochem Photobiol B 2002;76:518–25.

3. Witjes JA, Redorta JP, Jacqmin D, et al. Hexaminoelvulinate-guided fluorescence cystos-copy in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: review of the evidence and recommendations. Eur Urol 2010;57:607–14.

4. Schmidbauer J. Witjes F, Schmeller N, et al. Hexvix PCB3101/01 Study Group. Im-proved detection of urothelial carcinoma in situ with hexaminoelevulinate fluorescence cystoscopy. J Urol 2004;171:135–8.

5. Jocham D, Witjes F, Wagner S, et al. Improved detection and treatment of bladder cancer using hexaaminoelevulinate imaging: a prospective, phase III multicenter study. J Urol 2005;174:862–6.

6. Fradet Y, Grossman HB, Gomella L, et al. A comparison of hexaminoelevulinate fluores-cence cystscopy and white light cystoscopy for the detection of carcinoma in situ in pa-tients with bladder cancer: a phase III, multicenter study. J Urol 2007;178:68-73.

7. Thomas K, O’Brien T. Blue-sky in thinking about the blue-light. BJU Int 2009;104; 887–90.

8. Pusztaszeri M, Hauser J, Iselin C, et al. Urothelial carcinoma “nested variant” of renal pelvis and ureter. J Urol 2007;69:778.e15–7.

9. Holmang S, Johansson SL. The nested variant of transitional cell carcinoma—a rare neo-plasm with poor prognosis. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2001;35:102–5.

10. Shanks JH, Iczkowski KA. Divergent differentiation in urothelial carcinoma and other bladder cancer subtypes with selected mimics. Histopathology. 2009 ;54:885–900.

11. Liu JJ, Droller, MJ, Liao, JC. New Optical Imaging Technologies for Bladder Cancer: Considerations and Perspectives. J Urol 2012; 188:361–8

12. Cardillo M, Reuter VE, Lin O. Cytologic features of the nested variant of urothelial car-cinoma: a study of seven cases. Cancer 2003;99:23–7.

Date added to bjui.org: 11/04/2013

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-066-web