Editorial: Measuring testicular asymmetry in healthy adolescent boys

The Antwerp group has provided major contributions in the field of the adolescent varicocoele before [1], leveraging their long follow‐up and school‐based screening. Here, the focus is on ultrasound measures of testis volume and the natural variation in testis size detected in healthy boys without varicocoele [2].

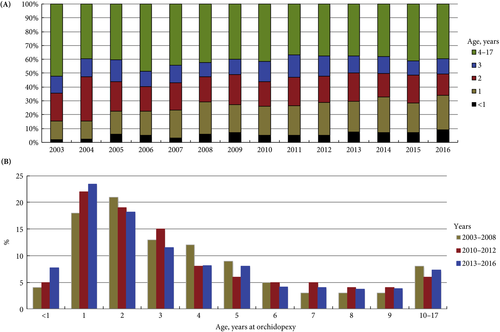

The cohort is a mix of secondary school evaluations and those recruited at a tertiary hospital. Hospital‐recruited subjects would be concerning for this study design, but fortunately the prevalence of medical conditions in this cohort mirrors that of other population‐based investigations (16.3% clinical varicocoele, 3.5% cryptorchidism). This reassures the reader that the results seen here are generalizable, with the caveat that it is nearly 85% Caucasian. Further favouring generalisability, we calculate the mean body mass index of the cohort at approximately the 58th percentile by Center for Disease Control and Prevention tables.

In total, 13% of screened boys had a left testis 2 mL smaller than the right, a fact made more pronounced by the younger skew of the cohort – given the known variance in ultrasound measurement it would be more likely to detect such a difference with larger volumes. With larger measures, a small linear underestimate is more likely to trigger the 2 mL volume difference as a function of geometry. The authors assert that the testicular atrophy index is normally distributed. In the narrowest sense this is unlikely to be true, as the test statistics required (e.g. Shapiro–Wilk) are not shown and are quite strict. Nevertheless, the spirit of this claim stands as without a doubt there is a ‘curve’, and readers expected to find perfect symmetry in the ultrasound‐measured gonadal size of healthy boys will be disappointed.

The authors have advanced yet another measurement of testicular asymmetry, modifying the existing testicular atrophy index, and this is difficult to support. The field is already crowded with an alphabet soup of such measures, and this new one is not algebraically equivalent to those extant [3]. It would serve us all well to agree upon a standard.

There are implications from this research on practice. The European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines state that urologists should ‘perform surgery for […] varicocele associated with a small testis (size difference of >2 mL or 20%)’ at level of evidence 2 and grade of recommendation B [4]. In the absence of comment on persistence or longitudinal follow‐up, this is a position that both we and the authors oppose. We favour longitudinal measurements and a semen analysis, should the boys reach Tanner V status. The authors take this a step further and suggest that volume differential calculations should be used with ‘great caution’. Here we differ from the authors in opinion; difference in testis volume, especially in extremes, does appear to be associated with low total motile sperm counts, and we believe that such measures have their place [5,6].

The primary implication of this paper [2] is that differential in testis volume is common and benign. The reader should be cautioned that the latter has not been proven as the control boys have not produced semen samples or demonstrated paternity. We know only that the studied boys are presumed healthy, not fertile. There are additional limitations, largely noted by the authors. This is a cross‐sectional study, and it would be interesting to see if the volume differences are transient or persistent, as they could be present due to measurement artefact or a natural difference in growth. The growth curves by boxplot are useful, but perhaps less so than formal growth chart with percentiles (which require sophisticated techniques to generate [7]). This work also serves as a reminder that in clinical classification of adolescent development, recording Tanner stage by both genital and hair development is most rigorous.

We join the authors in cautioning against using a single volume‐based data point, such as a fixed or proportional difference in testis volumes, as a decision for surgery.

Michael P. Kurtz and David A. Diamond

Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

References

- Bogaert G, Orye C, De Win G. Pubertal screening and treatment for varicocele do not improve chance of paternity as adult. J Urol 2013; 189: 2298–303

- Vaganée D, Daems F, Aerts W et al. Testicular asymmetry in healthy adolescent boys. BJU Int 2018; 122: 654–66

- Christman MS, Zderic SA, Kolon TF. Comparison of testicular volume differential calculations in adolescents with varicoceles. J Pediatr Urol 2014; 10: 396–8

- European Association of Urology. European Association of Urology Guidelines, 2015 Edition. Available at: https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/EAU-Extended-Guidelines-2015-Edn.pdf. Accessed May 2018

- Keene DJ, Sajad Y, Rakoczy G, Cervellione RM. Testicular volume and semen parameters in patients aged 12 to 17 years with idiopathic varicocele. J Pediatr Surg 2012; 47: 383–5

- Kurtz MP, Zurakowski D, Rosoklija I et al. Semen parameters in adolescents with varicocele: association with testis volume differential and total testis volume. J Urol 2015; 193(Suppl.): 1843–7

- Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and Development. Series 11, Number 246. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_11/sr11_246.pdf. Accessed May 2018