Whilst extended pelvic lymphadenectomy has become part of standard care in select patients undergoing radical prostatectomy at some centres, it is not universally accepted or performed and remains controversial, so why is this? The most common reasons cited for not performing a node dissection, or at least an extended node dissection, include lack of proven therapeutic benefit and the increased operative time and risk of complications. But do we really need to show a survival benefit to accept the role of extended pelvic lymphadenectomy for patients undergoing radical prostatectomy? It would take a randomised trial run over at least a decade, thousands of patients and untold cost to prove or disprove. Although randomised trials can be invaluable in assessing some aspects of medical or surgical care, they are not always appropriate or even desirable for surgical outcomes as O’Brien et al eloquently illustrated. What’s more, results from RCTs in surgery can be misleading – consider the Prostate Cancer Intervention Versus Observation Trial, in which overall survival at a median follow-up of 10 years was approximately 50% in both arms. This is equivalent to the overall survival in the observation arm of Messing’s trial, in which virtually no patients died of non-prostate cancer causes and contrasts starkly with the current life expectancy of 65 year old males in Australia of 20 years. Patients in PIVOT weren’t living long enough to die from prostate cancer!

Whilst extended pelvic lymphadenectomy has become part of standard care in select patients undergoing radical prostatectomy at some centres, it is not universally accepted or performed and remains controversial, so why is this? The most common reasons cited for not performing a node dissection, or at least an extended node dissection, include lack of proven therapeutic benefit and the increased operative time and risk of complications. But do we really need to show a survival benefit to accept the role of extended pelvic lymphadenectomy for patients undergoing radical prostatectomy? It would take a randomised trial run over at least a decade, thousands of patients and untold cost to prove or disprove. Although randomised trials can be invaluable in assessing some aspects of medical or surgical care, they are not always appropriate or even desirable for surgical outcomes as O’Brien et al eloquently illustrated. What’s more, results from RCTs in surgery can be misleading – consider the Prostate Cancer Intervention Versus Observation Trial, in which overall survival at a median follow-up of 10 years was approximately 50% in both arms. This is equivalent to the overall survival in the observation arm of Messing’s trial, in which virtually no patients died of non-prostate cancer causes and contrasts starkly with the current life expectancy of 65 year old males in Australia of 20 years. Patients in PIVOT weren’t living long enough to die from prostate cancer!

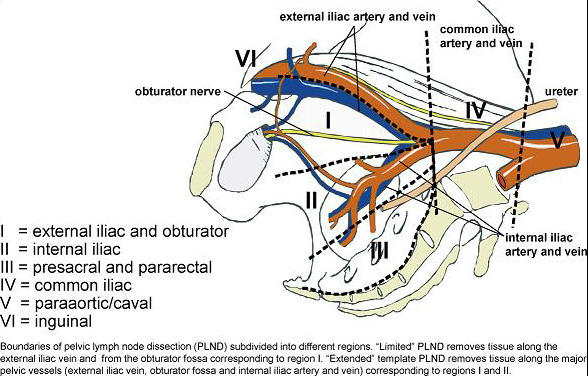

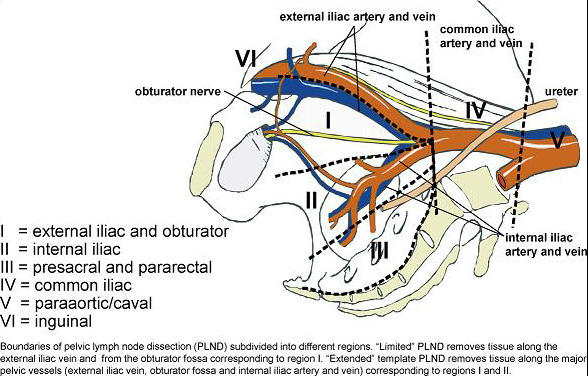

There is no doubt that for accurate nodal staging, an extended lymphadenectomy is currently the gold standard, as reflected in the EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Two very elegant trials in recent years assessed the performance of similar templates in terms of staging accuracy and concluded that a modified extended template struck the right balance between accuracy and risk of complications. Joniau et al, showed in a prospective cohort of 74 patients, around half of whom were lymph node positive, a modified extended template including the pre-sacral nodes had a staging accuracy of 97% and removed 88% of positive nodes. Omitting the pre-sacral nodes accurately staged 94% of patients and removed 76% of positive nodes. Mattei et al concluded that their modified ePLND removed approximately 75% of “sentinel” nodes in a prospective series of 34 node negative patients. Whether a “modified” ePLND or “plain” ePLND is performed, the staging accuracy is significantly better than a “standard” PLND, which omits the nodes around the internal iliac vessels and according to Joniau et al would accurately stage 76% of patients and remove only 29% of positive nodes. A “limited” node dissection, removing only the tissue within the obturator fossa performed even worse, staging 47% and removing just 15% of positive nodes.

From Mattei et al European Urology 2008, 53:118-125

But what is the real value in accurate nodal staging? Does it change patient management? The Messing trial showed that node positive patients who received adjuvant hormone therapy had improved CSS and OS compared to node positive patients observed until clinical progression. The study, however, has limited application to current real life patient management. Whilst patients with high volume nodal disease are likely to benefit from adjuvant hormone therapy, some patients with node positive disease, particularly those with micro-metastatic disease, will not suffer biochemical progression let alone clinical progression and therefore may not warrant ADT. Furthermore, most patients will be commenced on hormone therapy according to specific PSA criteria long before clinical progression. Despite these apparent weaknesses, the CSS and OS are remarkably similar to many retrospective series of node positive patients outside trials and managed in “real life”. Bader and Schumacher presented series of 92 and 122 node positive patients respectively, none of who received adjuvant hormone therapy. Ten year CSS for both of these series was approximately 60% and 10-yr OS in the Schumacher cohort was 53%, almost identical to the 10-yr OS in the Messing trial. Conversely, a number of retrospective series of node positive patients in which all, or almost all patients received AHT, 10-yr CSS ranged between 74-86% and 10-yr OS was 60 – 67%. These outcomes are similar to the AHT arm in Messing’s trial, in which 10-yr CSS was 85% and 10-yr OS was 75%. This is far from compelling evidence in favour of AHT in node positive patients, but it is certainly food for thought.

Rather than treat all node positive patients equally, however, we should be more sophisticated in our approach. Briganti and Schumacher have shown that patients with 1 or 2 positive lymph nodes have better 10-yr CSS than patients with 3 or more positive nodes whether they receive adjuvant hormone therapy or not. In Schumacher’s series, 10-yr CSS was 72-79% for patients with 1 and 2 positive nodes, versus 33% for patients with 3 or more positive nodes, without AHT. In Briganti’s series, 10-yr CSS for patients with 3 or more positive nodes was 73% and they were almost twice as likely to die from prostate cancer than those with fewer than 3 nodes positive. All patients received AHT. Perhaps then, we should consider patients with higher volume nodal disease on extended pelvic lymphadenectomy for immediate adjuvant hormone therapy, whilst those with micro-metastatic disease may be suitable for observation until predetermined PSA criteria are reached.

Beyond the staging benefit, Jindong et al recently published a prospective, randomised trial showing a BCR free survival benefit for patients undergoing extended versus standard pelvic lymphadenectomy. With a median follow-up of just over 6 years, intermediate risk patients undergoing ePLND had a 12% absolute reduction in biochemical recurrence (73.1% v 85.7%) and high risk patients more than 20% (51.1% v 71.4%) compared to those undergoing a standard node dissection. This may eventually translate into a survival benefit, or at least a clinical progression benefit, but in this cohort of patients, a reduction in biochemical recurrence means a reduction in the numbers requiring salvage radiation therapy and salvage androgen deprivation and the consequent side-effects and complications of these treatments.

It is clear the complication rate following ePLND is higher than with sPLND or no node dissection, but a recent review revealed the difference is accounted for by an increase in the incidence of symptomatic lymphoceles, most of which resolve with conservative management. Ureteric, nerve and major vascular injuries are rare. This would appear to be a much more acceptable complication profile than that following salvage radiotherapy, or androgen deprivation. Although uncommon, membranous urethral stricture following salvage radiation often confers debilitating and enduring morbidity. Continence and potency rates also suffer, not to mention bowel toxicity. A 20% absolute reduction in biochemical recurrence may also swing the pendulum away from adjuvant radiation in high risk disease, benefiting even more patients.

Proving a survival benefit with level 1 evidence is the holy grail of medical and surgical trials, but it is not the only outcome to consider. Biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy carries significant psychological burden and salvage therapies can carry significant morbidity. Disease recurrence is most common in the high risk population and there is now level 1 evidence of a real benefit to these patients when ePLND is included as part of their surgical care.

Dr Philip E Dundee

Epworth Prostate Centre and The Royal Melbourne Hospital

T: @phildundee