Robotic surgery trial exposes limitations of randomised study design

Here it is, the highly anticipated randomised controlled trial of open versus robotic radical prostatectomy published today in The Lancet. Congratulations to the team at Royal Brisbane Hospital for completing this landmark study.

The early headlines around the world include everything from this one in the Australian Financial Review:

– to this from The Telegraph in London

– to this from The Telegraph in London

As ever, there will be intense and polarising discussion around this. One might expect that a randomised controlled trial, a true rarity in surgical practice, might settle the debate here; however, it is already clear that there will be anything BUT agreement on the findings of this study. Why is this so? Well let’s look first at what was reported today.

As ever, there will be intense and polarising discussion around this. One might expect that a randomised controlled trial, a true rarity in surgical practice, might settle the debate here; however, it is already clear that there will be anything BUT agreement on the findings of this study. Why is this so? Well let’s look first at what was reported today.

Study design and findings:

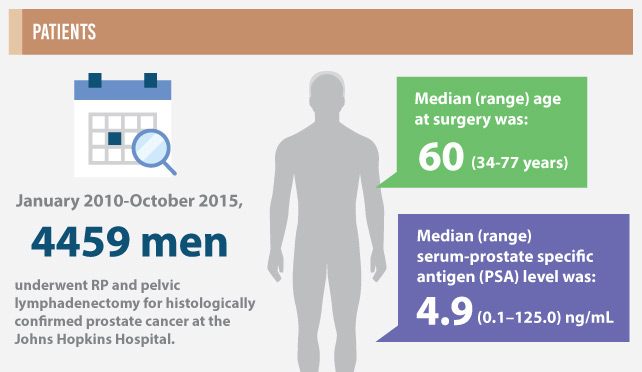

This is a prospective randomised trial of patients undergoing radical prostatectomy for localised prostate cancer. Patients were randomised to undergo either open radical prostatectomy (ORP, n=163) or robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP, n=163). All ORPs were done by one surgeon, Dr John Yaxley (JY), and all RARPs were done by Dr Geoff Coughlin (GC). The hypothesis was that patients undergoing RARP would have better functional outcomes at 12 weeks, as measured by validated patient-reported quality of life measures. Other endpoints included positive surgical margins and complications, as well as time to return to work.

So what did they find? In summary, the authors report no difference in urinary and sexual function at 12 weeks. There was also no statistical difference in positive surgical margins. RARP patients had a shorter hospital stay (1.5 vs 3.2days, p<0.0001) and less blood loss (443 vs 1338ml, P<0.001), and less pain post-operatively, yet, these benefits of minimally-invasive surgery did not translate into an earlier return to work. The average time to return to work in both arms was 6 weeks.

The authors therefore conclude by encouraging patients “to choose an experienced surgeon they trust and with whom they have a rapport, rather than choose a specific surgical approach”. Fair enough.

In summary therefore, this is a randomised controlled trial of ORP vs RARP showing no difference in the primary outcome. One might reasonably expect that we might start moth-balling these expensive machines and start picking up our old open surgery instruments. But that won’t happen, and my prediction is that this study will be severely criticized for elements of its design that explain why they failed to meet their primary endpoint.

Reasons why this study failed:

1. Was this a realistic hypothesis? No it was not. For those of us who work full-time in prostate cancer, the notion that there would be a difference in sexual and urinary function at 12 weeks following ORP or RARP is fanciful. It is almost like it was set up to fail. There was no pilot study data to encourage such a hypothesis, and it remains a mystery to me why the authors thought this study might ever meet this endpoint. I hate to say “I told you so”, but this hypothesis could never have been proved with this study design.

2. There is a gulf in surgical experience between the two arms. The lack of equipoise between the intervention arms is startling, and of itself, fully explains the failure of this study to meet its endpoints. I should state here that both surgeons in this study, JY (“Yax”) and GC (“Cogs”), are good mates of mine, and I hold them in the highest respect for undertaking this study. However, as I have discussed with them in detail, the study design which they signed up to here does not control for the massive difference in radical prostatectomy experience that exists between them. Let’s look at this in more detail:

- ORP arm: JY was more than 15 years post-Fellowship at the start of this study, and had completed over 1500 ORP before performing the first case in the trial.

- RARP arm: GC was just two years post-Fellowship and had completed only 200 RARP at the start of the study.

The whole world knows that surgeon experience is the single most important determinant of outcomes following radical prostatectomy, and much data exists to support this fact. In the accompanying editorial, Lord Darzi reminds us that the learning curve for functional and oncological outcomes following RARP extends up to 700 cases. Yes 700 cases of RARP!! And GC had done 200 radical prostatectomies prior to operating on the first patient in this study. Meanwhile his vastly more experienced colleague JY, had done over 1500 cases. The authors believe that they controlled for surgeon heterogeneity based on the entry numbers detailed above, and state that it is “unlikely that a learning curve contributed substantially to the results”. This is bunkum. It just doesn’t stack up, and none of us who perform this type of surgery would accept that there is not a clinically meaningful difference in the experience of a surgeon who has performed 200 radical prostatectomies, compared with one who has performed 1500. Therein lies the fundamental weakness of this study, and the reason why it will be severely criticized. It would be the equivalent of comparing 66Gy with 78Gy of radiotherapy, or 160mg enzalutamide with 40mg – the study design is simply not comparing like with like, and the issue of surgeon heterogeneity as a confounder here is not accounted for.

3. Trainee input is not controlled for – most surprisingly, the authors previously admitted that “various components of the operations are performed by trainee surgeons”. One would expect that with such concerns about surgeon heterogeneity, there should have been tighter control on this aspect of the interventions. It would have been reasonable within an RCT to reduce the heterogeneity as much as possible by sticking to the senior surgeons for all cases.

Having said all that, John and Geoff are to be congratulated for the excellent outcomes they have delivered to their patients in both arms of this study. These are excellent outcomes, highly credible, and represent, in my view, the best outcomes to be reported for patients undergoing RP in this country. We are all too familiar with completely unbelievable outcomes being reported for patients undergoing surgery/radiotherapy/HIFU etc around the world, and we have a responsibility to make sure patients have realistic expectations. John and Geoff have shown themselves to be at the top of the table reporting these credible outcomes today.

“It’s about the surgeon, stupid”

To paraphrase that classic phrase of the Clinton Presidential campaign of 1992, this study clearly demonstrates that outcomes following radical prostatectomy are about the surgeon, and not about the robot. Yet one of the co-authors, a psychologist, comments that, “at 12 weeks, these two surgical approaches yielded similar outcomes for prostate cancer patients”. Herein lies one of the classic failings of this study design, and also a failure of the investigators to fully understand the issue of surgeon heterogeneity in this study. It is not about the surgical approach, it is about the surgeon experience.

If the authors had designed a study that adequately controlled for surgeon experience, then it may have been possible for the surgical approach to be assessed with some equipoise. It is not impossible to do so, but is certainly challenging. For example a multi-centre study with multiple surgeons in each arm would have helped balance out the gulf in surgical experience in this two-surgeon study. Or at the very least, the authors should have ensured that they were comparing apples with apples by having a surgeon with in excess of 1500 RARP experience in that arm. Another approach would have been to get a surgeon with huge experience of both procedures (eg Dr Smith at Vanderbilt who has performed >3000 RARP and >3000 ORP), and to randomise patients to be operated on only by a single surgeon with such vast experience. That would have truly allowed the magnitude of the surgical approach effect to be measured, without the bias inherent in this study design.

Robotic surgery bridges the experience gap:

Having outlined these issues with surgeon heterogeneity and lack of equipoise, there is another angle which my colleague Dr Daniel Moon has identified in his comments in the Australian media today and which should be considered.

Although this is a negative study which failed to meet its primary endpoints, it does demonstrate that a much less experienced surgeon can actually deliver equivalent functional and oncological outcomes to a much more experienced surgeon, by adopting a robotic approach. Furthermore, his patients get the benefits of a minimally-invasive approach as detailed in the paper. This therefore demonstrates that patients can be spared the inferior outcomes that may be delivered by less experienced surgeons while on their learning curve, and the robotic approach may therefore reduce the learning curve effect.

On that note, a point to consider would be what would JY’s outcomes have been in this study if he had 13 years and 1300 cases less experience to what he had entering this study? Would the 200 case experience-Yax have been able to match the 1500 case experience-Yax?? Surely not.

And finally, just as a footnote for readers around the world about what is actually happening on the ground following this study. During the course of this study, the ORP surgeon JY transitioned to RARP, and this is what he now offers almost exclusively to his patients. Why is that? It is because he delivers better outcomes by bringing a robotic approach to the vast surgical experience that he also brings to his practice, and which is of course the most important determinant of better outcomes.

Sadly, “Yax” and “Cogs”, the two surgeons who operated in this study, have been prevented from speaking to the media or to being quoted in or commenting on this blog, but we are looking forward to hearing from them when they present this data at the Asia-Pacific Prostate Cancer Conference in Melbourne in a few weeks.

Declan G Murphy

Associate Editor BJUI; Urologist & Director of Genitourinary Oncology, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Australia

Twitter: @declangmurphy