1Department of Medical Oncology, University Hospital Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium.

2Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, AZ St Dimpna, Geel, Belgium.

3Department of Head and Neck Surgery, AZ St Dimpna, Geel, Belgium.

Abstract

Everolimus is commonly used as a second line therapeutic option in the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). Angioedema is a well described adverse event of everolimus treatment in the transplant area, where it is used as an immunosuppressant. However this is an extremely rare adverse event when everolimus is used in the treatment of mRCC.

We describe a case of an acute onset of severe everolimus-induced lingual angioedema in a 70 year-old man, who received everolimus 10 mg in the treatment of mRCC. Complete resolution occurred when everolimus was withdrawn. After re-administration of a reduced dose no recurrence was observed during a follow-up period of 11 months. During and after the onset of lingual angioedema, we opted not to terminate the administration of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, showing that everolimus was synergistic for the occurrence of this event.

We concluded that the occurrence of lingual angioedema in this particular case was an adverse event associated with everolimus treatment. In the literature, as in our case, a strong association between the co-administration of an ACE inhibitor and an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is described.

Introduction

Targeted therapy is now the standard treatment for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). In recent years, there have been a series of phase III randomized trials showing benefit of targeted therapy, i.e. the small molecule multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors sunitinib [1], sorafenib [2] and pazopanib [3], the vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor bevacizumab [4] and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors everolimus [5] and temsirolimus [6].

Everolimus demonstrated a significant improvement in progression free survival of 4.9 months versus 1.9 months for placebo in the phase III RECORD-1 study [5]. Upcoming are a phase II RECORD-2 study [7], everolimus and bevacizumab versus interferon alfa and bevacizumab in first-line, and a phase II RECORD-3 study [8], everolimus as first-line therapy followed by second-line sunitinib versus sunitinib as first-line followed by second-line everolimus. Usage of everolimus is an important contributor in the treatment of mRCC. Other tumor types in which mTOR inhibitors are explored include breast cancer, GIST, gastric carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma and B-cell lymphoma. [9]

The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events for mTOR inhibitors are hyperlipidaemia, hyperglycaemia, stomatitis, non-infectious pneumonitis and myelosuppression. [5, 6] In this case we report a potentially fatal [10] but rare toxicity: lingual angioedema.

Case

We present a 70-year old white male who underwent a nephrectomy for a pT1bN0M0 renal cell carcinoma of the clear cell type, who developed diffuse skin, bone, lung and lymph node metastases 14 years later. After radiotherapy to a single bone metastasis in the tibia, he initially started on sorafenib 400 mg bid. One and a half years later the patient progressed and at that time he opted to participate into the RAD001 expanded access trail. He received oral everolimus 10 mg qd.

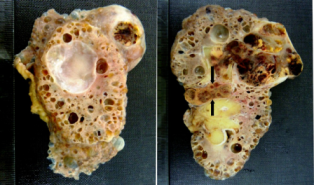

114 days after initiation of this therapy, he experienced a progressive swelling and a burning sensation of the tongue at 3:00 am. Within an hour he presented to the emergency department with a vast, swollen and oedematous tongue, as a result of which he wasn’t able to close his mouth (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Lingual angioedema five hours after presentation

He was unable to speak and had stridorous breathing. Physical examination revealed diffuse bilateral swelling and redness of the base of the mouth, the soft palate and the tongue. He did not have hives, pruritus, nor were there signs of peripheral edema. The patient did not have a history of allergic reactions and these symptoms occurred for the first time in his life. His concurrent medications included quinapril 5 mg qd, indapamide 2.5 mg qd and atorvastatine 20 mg qd.

At the time of presentation, total and differential leukocyte counts, thrombocyte counts, liver enzymes and coagulation factors were within the normal range. However, there was a marked rise in the fibrin degradation products and iron deficiency anaemia.

Indirect laryngoscopy revealed diffuse nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal and laryngeal swelling without critical airway obstruction. Chest X-ray showed no significant abnormalities. He was diagnosed with lingual angioedema.

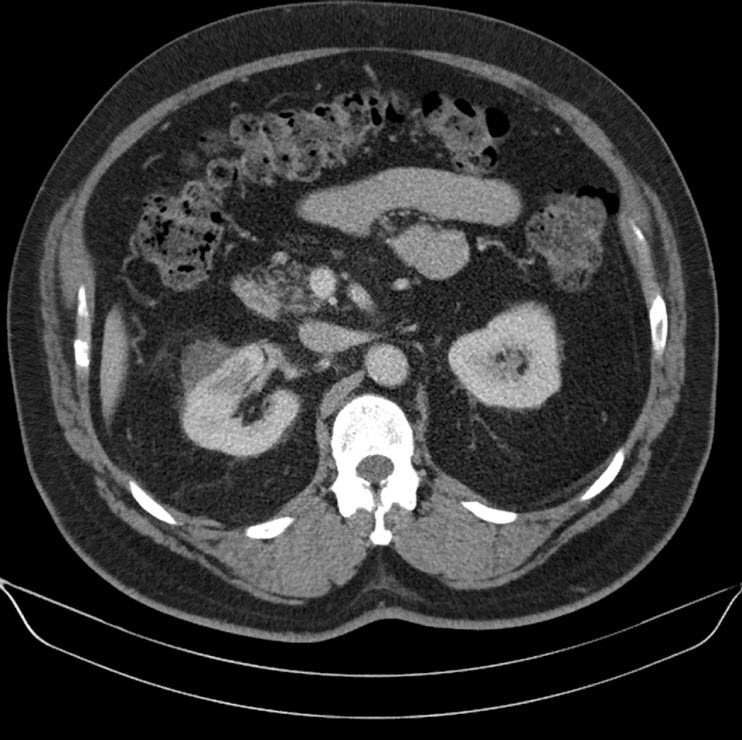

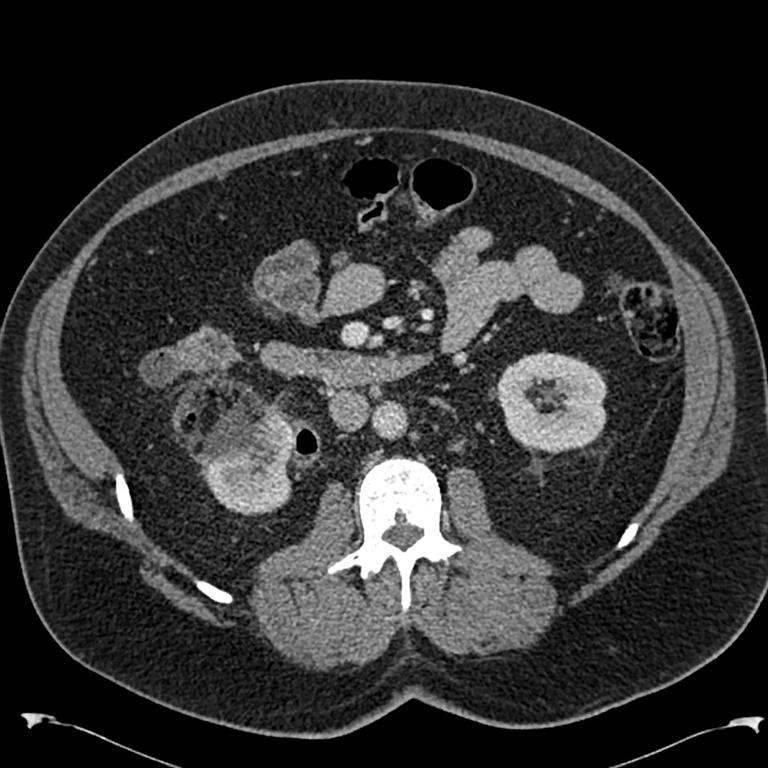

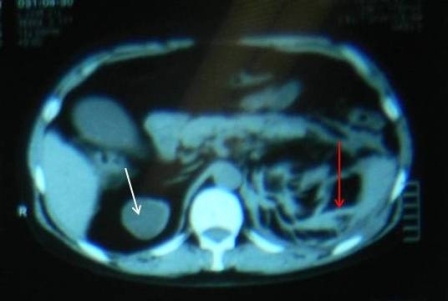

Everolimus was discontinued and intravenous treatment with methylprednisolone 125 mg, ranitidine 50 mg, promethazine 25 mg and cetirizine 10 mg was started and improved the patients’ symptoms. The dosages of his other medications, including quinapril, were not altered. Although the progression of the swelling was clearly brought to a halt five hours after administration of medication, there was no decrease noted in the volume of the tongue. Therefore intravenous hydrocortisone 250 mg in combination with ranitidine 50 mg was administrated and a CT scan was performed. The CT scan (Figure 2) revealed narrowing of the naso- and oropharynx, a dilated soft palate and an unmistakable voluminous tongue.

Figure 2. Computed tomography showing nearly complete obstruction of the oropharynx and obvious swelling of the tongue

He remained hospitalised for four more days in which time he received a declining dose of methylprednisolone, starting at 40 mg qd. His tongue returned to normal 18 hours after commencement. He was discharged with methylprednisolone 16mg qd for three more days.

Everolimus was re-administered nine days after the initial event at a reduced dose of 5 mg per day. More than 11 months after reinitiation, there has been no recurrence.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the second reported case of lingual angioedema as a result of using a mTOR inhibitor in the treatment of mRCC. Mackenzie and Wood [11] described a 61-year old man treated with everolimus 10 mg qd in second line and who developed lingual angioedema after 21 days of treatment. Interestingly this patients’ concurrent medication also contained an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, ramipril 10mg qd. Everolimus was initially stopped, but resumed one week later with no recurrence of the noticed side-effect.

In transplant medicine, there is longstanding clinical experience with mTOR inhibitors, where sirolimus and everolimus have been used as immunosuppressants. Everolimus is administrated at a dosage of 3 mg qd, as part of triple therapy, together with a calcineurin inhibitor and prednisone. Calcineurin inhibitors (like cyclosporine and tacrolimus) and everolimus are both metabolized by the CYP3A4 isoenzyme system, and their concomitant administration increases everolimus exposure by 2- to 3-fold. [12]

The largest series reports on 309 german kidney transplant recipients who had received mTOR inhibitors as immunosuppressants. Nine patients developed angioedema after a mean period of 123 days under combined therapy of an mTOR- and an ACE inhibitor. Six of these nine patients ceased the administration of the ACE inhibitor, no recurrence took place. In the three patients who continued to take the ACE inhibitor, angioedema recurred. All patients continued their mTOR inhibitor after the onset of the angioedema. In seven patients the everolimus or sirolimus levels were measured at the time of the event and six of them had increased plasma concentration levels. After replacement of the ACE inhibitor by an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) no recurrence was noticed. [13]

Stallone et al [14] were in 2004 the first to report the development of lingual angioedema in five kidney transplant recipients, one month after initiating the combination everolimus and an ACE inhibitor. Interestingly, in these five patients both drugs were administered at high dosages. The sirolimus dosage was decreased and the ACE inhibitor was stopped, but later reintroduced without recurrence of the assumed side effect. The authors hypothesized a dosage dependent synergistic effect when combining both drugs.

No reports of temsirolimus associated with lingual angioedema were found. Of note, temsirolimus is not used in the transplant population and is a newer agent.

Angioedema is a well-known side effect of ACE inhibitors. The OCTAVE trial reported the occurrence of ACE inhibitor induced angioedema in 0,68% out of >12,000 patients. [15] 99% of all cases present within the first year of therapy, of which a clear majority present within the first 8 weeks. [15, 16] Our patient had taken quinapril, in a low dose, for 2 years and 9 months without any adverse clinical events.

The concomitant administration of everolimus and inhibitors or inducers of the CYP3A4 enzyme system may affect everolimus blood levels. Concomitant administration of typical CYP3A4 inhibitors (ketoconazole [17] and erythromycin [18]) has been shown to significantly increase everolimus maximum concentration and everolimus area under the curve.

ACE inhibitors are also metabolized by the CYP3A4 enzyme system. CYP3A4 interaction could be an important part in linking the occurrence of angioedema to the concomitant administration of everolimus and an ACE inhibitor.

Furthermore, the incidence of angioedema is greater in the transplant setting. This might be because of the additional CYP3A4 interactions induced by the administration of calcineurin inhibitors.

Conclusion

In recent years different types of cancer are being treated by targeted therapy, given the relatively favorable side effects in comparison to chemotherapy. An impressive advance, especially in renal cell cancer, is made in increasing overall survival and disease free survival due to the specialized form of inhibiting tumor proliferation and differentiation.

In an area where targeted therapy is being examined and experimented on all types of cancer, one must never forget to think about possible drug interactions and side effects.

We describe the occurrence of lingual angioedema due to everolimus treatment. As in our patient, literature revealed a strong association with concomitant administration of ACE inhibitors. We demonstrated that interrupting everolimus therapy, while continuing the ACE inhibitor, led to a resolution of lingual angioedema. Furthermore we showed that a rechallenge with a reduced dose of everolimus within two weeks after the initial event was safe and the patient could be treated for a further 11 months.

Dosage of everolimus and drug interaction most probably play an important role in the pathogenesis of lingual angioedema.

References

1. Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:115-124.

2. Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:125-134.

3. Sternberg Co, Davis ID, Mardiak J et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trail. J Clin Oncol 2010; 8:1061-1068.

4. Escudier B, Pluzanska A, Koralewski P et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet 2007; 370:2103-2111.

5. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet 2010; 372:449-456.

6. Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2271-2281.

7. NCT00719264: A randomized, open-label, multi-center phase II study to compare bevacizumab plus RAD001 versus interferon alfa-2a plus bevacizumab for the first-line treatment of patients with metastatic clear cell carcinoma of the kidney. Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Last accessed Dec 22, 2009.

8. NCT00903175: Efficacy and safety comparison of RAD001 versus sunitinib in the first-line and second-line treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Last accessed Jun 23, 2009.

9. Chan H, Grossman AB, Bukowski RM. Everolimus in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma and neuroendocirne tumors. Adv Ther 2010; 278:495-511.

10. Ulmer JL, Garvey MJ. Fatal angioedema associated with lisinopril. Ann Pharmacother 1992; 26:1245-6.

11. M. Mackenzie, L. A. Wood. Lingual angioedema associated with everolimus. Acta Oncologica 2010; 49:107-109.

12. Schaffer SA, Ross HJ. Everolimus: efficacy and safety in cardiac transplantation. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2010; 9:843-854.

13. Duerr M, Glander P, Iekmann F et al. Increased incidence of angioedema with ACE inhibitors in combination with mTOR inhibitors in kidney transplant recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5:703-708.

14. Stallone G, Infante B, Di Paolo S et al. Sirolimus and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors together induce tongue oedema in renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004; 19:2906-2908.

15. Kostis JB, Kim HJ, Rusnak J et al. Incidence and characteristics of angioedema associated with enalapril. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:1637-1642.

16. Schuster C, Reinhart WH, Hartmann K et al. Angioedema induced by ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II-receptor antagonists: analysis of 98 cases. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1999; 129:362.

17. Kovarik JM, Beyer D, Bizot MN et al. Blood concentrations of everolimus are markedly increased by ketoconazole. J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 45:514-158.

18. Kovarik JM, Beyer D, Bizot MN et al. Effect of multiple-dose erythromycin on everolimus pharmacokinetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 61:35-38.

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.