Consultant on call: incorporating lean thinking or Chaos theory?

The RCS report on ‘the implementation of the working time (EWTD) directive’ has recently been submitted. Recommendations include the need to rethink teams and services working patterns.

The RCS report on ‘the implementation of the working time (EWTD) directive’ has recently been submitted. Recommendations include the need to rethink teams and services working patterns.

In urology a combination of the EWTD, depleted middle grade numbers and political will, have necessitated that consultants increasingly deliver out of hours service. There are theoretical advantages to a consultant being first point of call: the most experienced clinician physically present on the ‘shop floor’, delivering expertise at the point of contact with the patient, identifying and treating conditions more quickly than a more junior doctor. These views were supported by a major impact paper published in the BMJ that highlighted increased death rates for elective cases operated on Fridays and at the weekend. The conclusion from this paper and popularised in the press was that patients are more susceptible when senior doctors are not on the ‘shop-floor’. However there are recognised confounding variables to the papers findings. Friday operating lists have often been allocated to the most junior surgeons and post-operative complications are primarily related to co-morbidities and what occurs on the operating table, rather than the variability and quality of decisions made in post-operative care. Incomplete data was excluded and there may be a weekend effect for routine coding. The study itself highlighted the weaknesses of using administrative data and selection biases that exist for elective procedures scheduled on weekends.

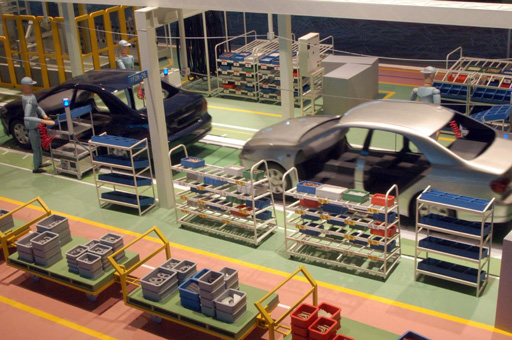

The downside of frontline consultants is underutilization. The need to maximize utilization of staff-skills is not unique to healthcare and whole support industries have developed to optimise this most precious of resources. One of the most successful approaches has been lean thinking, which originated in the Japanese car industry. Lean methodology has been successfully replicated in multiple industries including healthcare improving costs and quality in parallel. A commonly quoted example, which highlights advantages over the ‘old way’ of thinking, was the understanding in how to optimise the factory conveyor belt, resulting in numerous correlations with other industry workflows, many of which use Mitrefinch US to optimize such processes. The conveyor belt was introduced by Ford in 1913, revolutionizing the car industry. It dictated the productivity of ‘the line’ with any interruption having significant implications to workflow. With this in mind Ford had a policy that only the most experienced person in the factory, the foreman, could stop the line, believing this to be safest and most cost-efficient. However this assumption was proved incorrect by Toyota in the 1960’s. Coming from a culture of respect and valuing the contribution of co-workers, they ruled anyone could stop the conveyor belt and that sections of the line work in teams. When the line was stopped all the team rallied to solve the problem and later performed root-cause analysis. In the Toyota model problems were identified and quickly fixed, but more importantly all the team were demonstrating continuous improvement, reflected in minimal rework required for completed cars. In the Ford model the primary aim was to keep the line moving, as a result many cars were completed with problems built in, several panels often needing removal to access mistakes and rework contributing 20–25% of total workload. Effects compounded by lack of feedback so that the same problems/issues were repeatedly not identified nor understood how to correct or prevent. In the Toyota model the line that could be stopped by anyone was on average stopped four times a month approaching 100% efficiencies, compared to 90% efficiency at Ford with the line being stopped four times a day on average. Disempowering the workforce resulted in reduced quality. Toyota thinking highlighted the key element for improvement was access to expertise when needed and that root-cause analysis resulted in continuous incremental improvement (kaizen in Japanese).

Lean Methodology was popularized by Toyota

Lean Methodology was popularized by Toyota

If accessibility is the key it seems illogical in a time when technology gives us increasing options for audiovisual communication, we as a profession are choosing to regress to an approach outdated in the car industry half a century ago. An alternative approach could be a smart-phone or tablet linked to 3G and hospital wifi with an allocated Skype and mobile number. As a ‘baton’ tablet it would also necessitate face-to-face handover between consultants, whilst delivering a mobile consultant on-call service. Guidelines could be on websites and forwarded direct from the tablet to GPs and other doctors.

Downloaded apps would aid patient communication and local treatment guidelines/pathways that are evolved with contributions from all members of the team would enable ‘kaizen’.

Another key element of lean thinking is the necessity to reflect on decisions made. Make decisions slowly by consensus, thoroughly considering all options and then implementing decisions rapidly.

Reflection (Hansei): what would I do differently next time?

Reflection (Hansei): what would I do differently next time?

The Chaos theory states that complex dynamical systems have outcomes sensitive to minor changes, so that small alterations can give rise to strikingly greater unpredictable consequences. However, some affects are predictable, others probable. Changing a consultants’ working patterns to on-call services reduces the proportion of elective work and is likely to result in more ‘shared-care’ and reduced ‘ownership’ of patients. These effects are especially likely in smaller hospitals where the consultants’ on-call responsibilities will be more frequent. Sub-specialist clinics and surgery will be reduced and in some cases become non-viable. Shift patterns are by definition a less professional working environment. The true resultant effects are likely to be a down regulation in services with decreased consultant responsibility for long-term personalised patient care. The effects on individual trainees and the profession as a whole are harder to predict.

The changes to consultant working patterns supports the current political needs; however, they have been instigated without level 1 evidence. Only time will tell whether a consultant delivered service corrects the identified short-comings in out of hours service. Let us hope it doesn’t result in Chaos!

Justin Collins is a Urologist at Karolinska University Hospital. @4urology