Selected patients with pudendal neuralgia, dupuytren’s contracture, low back pain responded favourably to education, postural advice, and mobilisation and exercises directed to the lumbopelvic region.

Authors: Dornan, Peter R.1; Coppieters, Michel W.2

Corresponding Author: Dornan, Peter R.

Affiliations

(1): Peter Dornan Physiotherapy Centre

(2): Centre of Clinical Research Excellence in Spinal Pain, Injury and Health, School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, The University of Queensland

Corresponding author

Peter R. Dornan

Peter Dornan Physiotherapy Centre

13 Morley Street

Toowong (Brisbane)

QLD 4066

Australia

Tel: +61 7 3371 9155

Fax: +61 7 3871 0301

Email: [email protected]

Abstract

Objective: To investigate the effect of musculoskeletal management of the lumbopelvic region in patients with pudendal neuralgia and musculoskeletal dysfunctions in the lumbopelvic region.

Patients: Twenty-five male patients with pudendal neuralgia without a urological cause for the symptoms and with lumbopelvic musculoskeletal disorders participated.

Methods: The intervention consisted of explanation and postural advice, specific manual mobilisation techniques and motor control exercises for the lumbopelvic region. A modified Pelvic Pain Symptom Survey was used to evaluate changes in pain and sexual dysfunction at the end of treatment and at three months follow-up. A repeated-measure analysis of variance was used to analyse the data.

Results: At the end of the treatment period and at follow-up, pain and sexual dysfunction had improved significantly. Although 39% of patients had experienced limited recurrence of symptoms during the follow-up period, patients stated that a home exercise program was effective at reducing the symptoms and no additional treatment was sought.

Conclusion: This cohort study provides Level 2b evidence that a musculoskeletal treatment approach has a positive influence on pain and sexual dysfunction in a specific subgroup of patients presenting with pudendal neuralgia.

Introduction

Urologists and gynaecologists regularly see patients presenting with signs of pudendal nerve entrapment. Pudendal nerve entrapment is a recognised cause of chronic pelvic pain in the regions served by the pudendal nerve, typically presenting as pain in the penis, scrotum, labia, perineum or anorectal region [1, 2]. Other symptoms may include dysuria, urge incontinence, and pain during or after ejaculation[3]. There may be corresponding sexual and erectile dysfunction problems[4], including impotence[5].

These presentations demand a complete urological investigation by a medical specialist. For the majority of these patients there is a definite urological or gynaecolocial diagnosis, such as prostadynia (prostatitis), orchialgia (testicular pain) or vulvodynia (vulva pain)[6]. However, a sub-group of these patients does not have a clear diagnosis. Once prostate, gynaecological, urinary or rectal pathology has been excluded, patients are often referred for physiotherapy.

Many patients with signs and symptoms characteristic for pudendal neuralgia also present with low back pain, with or without groin, buttock and leg symptoms[7]. Furthermore, patients frequently indicate that sitting will either bring on or make the symptoms worse [3, 8]. One explanation for some of the symptoms is that they may be caused by a dysfunction in the thoracolumbar junction as described by Maigne [9, 10]. Maigne stated that referred pain from the spinal nerves T12 and L1 can manifest itself as low back pain, which mimics pain of lumbosacral or sacroiliac origin. Although less common, referred pain from the spinal nerves originating in the thoracolumbar junction can also be felt in the lower abdomen, the medial aspect of the upper thigh and the groin, labia majora or scrotum [9, 10]. Recommended treatment includes spinal manipulation of the thoracolumbar region and infiltration of the painful zygapophysial joint with a corticosteroid [9, 10].

It has also been suggested that a range of musculoskeletal disorders of the lumbopelvic region, such as altered intra-pelvic motion and pelvic muscle control, may cause entrapment, excessive strain or irritation of the pudendal nerve[4].

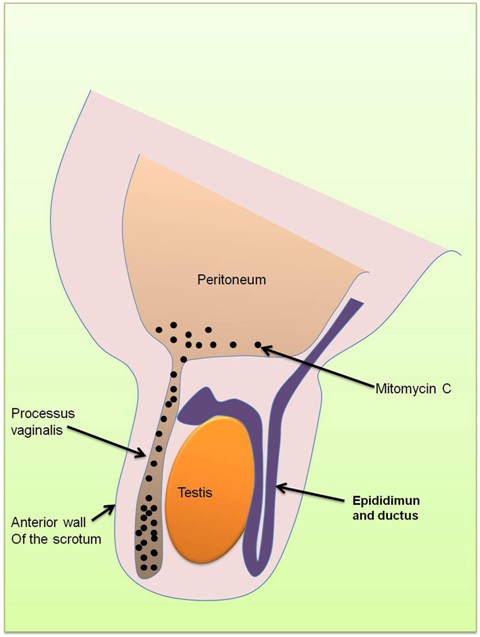

The pudendal nerve emerges from the sacral plexus (primarily S2-S4, with possible contributions from S1 and S5)[11]. The pudendal nerve enters the pelvic cavity approximately 3 cm. below the sacro-iliac joint. The nerve journeys posterior to the coccygeus muscle and descends ventral to the sacrotuberous ligament. According to Robert et al[1], the nerve passes under the sacrospinous ligament medial to the ischial spine and re-enters the pelvic cavity through the lesser sciatic foramen. Ramsden et al[3] have shown that the pudendal nerve re-enters immediately adjacent to the inferior border of the sacrospinous ligament. A perineal branch of the nerve, the inferior pudendal (long scrotal nerve) curves below and in front of the ischial tuberosity, pierces the fascia lata and runs to the skin of the scrotum in the male and the external labia in the female [12].

Ramsden et al [3] suggest that entrapment can occur between the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments. Entrapment may also occur in the pudendal canal [3] (also called Alcock’s canal), which is formed by a split of the fascia of the obturator internus muscle. Clinically, we have observed that pudendal neuralgia is often associated with articular dysfunctions in the lumbopelvic region.

There are no randomised clinical trials or case series available which have investigated whether musculoskeletal management of the lumbopelvic region could reduce pudendal neuralgia. Moreover, no treatment protocols have been suggested in this domain in the peer reviewed literature. The aim of this paper is therefore to propose a musculoskeletal management approach focussed on the lumbopelvic region for patients with pudendal neuralgia without urological pathology, and to evaluate its efficacy in a prospective cohort design.

Methods

Study design

A cohort of 25 consecutive male patients with pudendal neuralgia referred from urologists was included in this study. Outcome measures at the end of the treatment period and at three months follow-up were compared to baseline data. The study was approved by the Institutional ethics committee and all participants signed an informed consent form.

Participants

Patients were included in the study if their signs, symptoms and history fulfilled the definition of pudendal neuralgia [1, 2]. Patients were included if they presented with: (i) pain or other symptoms in one or more regions including the penis, scrotum, perineum, lower abdomen or anorectal region; (ii) pain during or after ejaculation; and/or (iii) dysuria, urge incontinence, sexual and erectile dysfunction problems or impotence.

To be eligible, patients were also required to have signs of a pelvic girdle dysfunction. Four pain provocation tests and one mobility test were performed to identify a sacroiliac joint dysfunction (see Appendix 1). All four provocation tests have been reported to have good inter-examiner reliability[13]. Following the recommendation of their use[14], two of the four tests had to be positive to reflect a diagnosis of sacroiliac joint dysfunction. In addition to the pain provocation tests, Gillet’s test for sacroiliac joint mobility[15] had to be positive. Herzog et al[16] demonstrated substantial reliability for this test.

Patients were excluded if they presented with a urological diagnosis, such as prostadynia.

The mean (±SD) age, weight and height of the 25 patients who participated in the study were 44 (±12) years, 84 (±13) kg and 180 (±6) cm, respectively. The mean (±SD) duration of symptoms was 47 (±70) months. The mean number of days pain was experienced in the month preceding the start of treatment was 18.7 (± 10.2) days.

Treatment

At the start of each treatment session, mild heat was applied to the patient’s lower back for 10 minutes (Physiotherm short wave diathermy). After the application of heat, a series of exercises was performed (see Appendix 2). The exercises were designed to mobilise the thoracolumbar spine and sacroiliac joint, and to retrain the muscles of the lumbopelvic region. After the exercises, manual techniques were performed. A mobilising technique for the sacroiliac joint was used which has been devised to mobilise a restricted anterior rotation of the innominate bone [15] (see Appendix 3). The clinical assumption was that this mobilisation technique could address a possible nutation of the sacrum or posterior rotation of the ilium which may have increased the stress on the pudendal nerve as it runs between the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligament.

In addition, explanation and advice was provided, including postural advice. Patients were encouraged to try to adopt a more physiological spinal curvature throughout the day, especially during sitting.

The rationale for this management approach was that via exercises and mobilisation techniques directed to the thoraco-lumbo-pelvic region, the mechanical provocation and irritation of the pudendal nerve might be reduced. Improvement of postural awareness might result in a healthier loading of the neuromusculoskeletal structures of the lumbopelvic area resulting in less provocation.

No predetermined number of treatment sessions was provided. The treatment was ended when patient and clinician believed no further improvements could be expected with the intervention under investigation.

Baseline and Outcome measures

The prime outcome measure in this study was the modified Pelvic Pain Symptom Survey (Appendix 4), which was a shortened version of the survey developed at the University of Washington[17] and Stanford University School of Medicine[7]. The survey included an 8 item pain domain, and a 5 item sexual dysfunction domain. For each item, the degree by which the symptoms troubled the patient was scored on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The survey also included an 11-point numeric rating scale to rate the intensity of the pain and a body chart to indicate the location of the symptoms.

The baseline and outcome measures were recorded before the start of treatment, at the end of the treatment period and at 3 month follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed with a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Of the 25 patients who participated, two participants could not be contacted at the three month follow up. For these two patients, baseline data were used in the analysis.

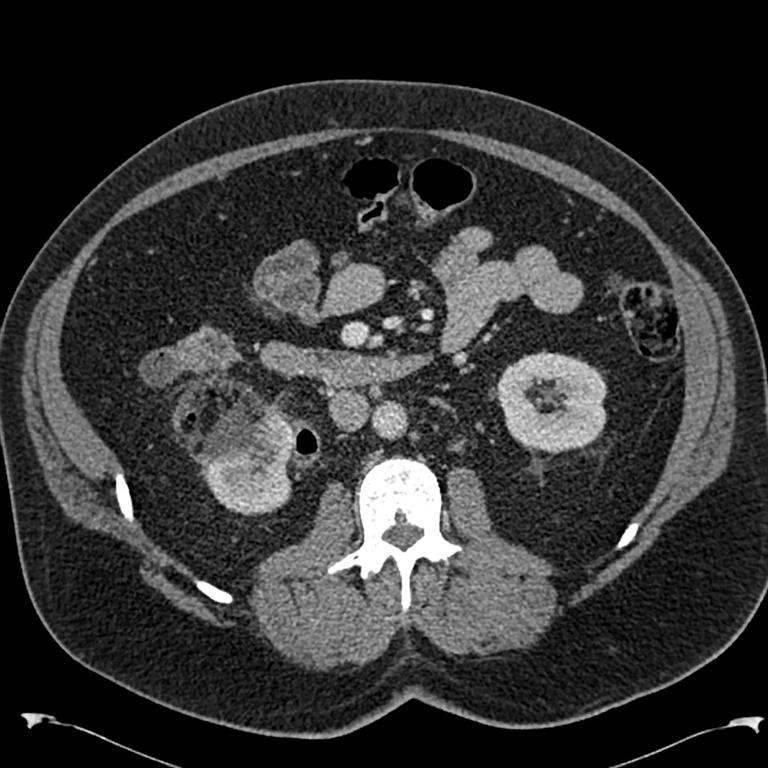

Results

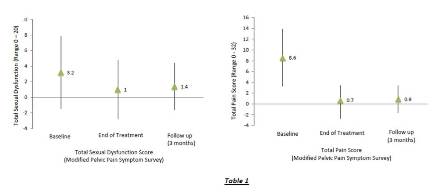

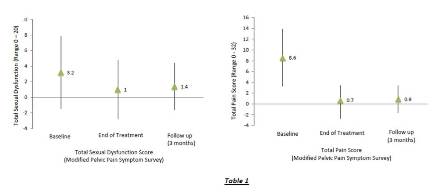

At baseline, the mean (± SD) overall pain intensity was 5.0 (± 2.1) on the numeric pain rating scale. The modified Pelvic Pain Symptom Survey revealed that all patients reported pain, predominantly in the testicles (80%), lower back (80%), and the abdomen or pubic area (68%). Forty eight percent of patients also reported some form of sexual dysfunction. Lack of interest (36%) was the most frequently cited dysfunction. Table 1 illustrates the mean severity for all items of the Pelvic Pain Symptom Survey.

The mean number of treatment sessions was 4.4, with a maximum of 16 sessions. The maximum treatment duration was three months.

At the end of the treatment period, the mean (± SD) overall pain intensity had decreased to 0.6 (± 2.0) (p < 0.001). The modified Pelvic Pain Symptom Survey demonstrated that the number of patients reporting pain had reduced substantially. Pain in the low back (8%) and penis (8%) were the most frequently cited locations, at much lower frequencies compared to baseline. Eight percent of patients reported some form of sexual dysfunction. Apart from the item ‘Difficulty ejaculation’ (p = 0.20), the analysis of variance demonstrated that all items of the Pelvic Pain Symptom Survey had improved significantly at the end of treatment when compared to baseline (p £ 0.021). Table 1 illustrates the improvement for the individual items of the modified Pelvic Pain Symptom Survey.

At three month follow-up, the mean (± SD) overall pain intensity was 0.8 (± 2.1) on the numeric pain rating scale. This was significantly lower than at baseline (p < 0.001) and not different compared to the end of treatment (p = 0.62). Compared to end of treatment, the number of patients reporting pain had risen to 20%. Low back pain (16%), pain in the testicles (12%) and penis (12%) were the most commonly listed areas. Sixteen percent of patients reported sexual dysfunction. All items of the Pelvic Pain Symptom Survey which had improved at the end of treatment were still improved at three month follow-up (p £ 0.042). None of the items at three month follow-up was significantly different compared to end of treatment (p ≥ 0.56), demonstrating that improvements were maintained.

Table 1 – Pain and Sexual Dysfunction Scores

Although symptoms had reduced significantly by the end of the treatment period and at the time of follow-up, nine of the 23 patients (39%) had experienced limited recurrence of symptoms during the three month follow-up period. These patients stated that the prescribed home exercise program was effective in relieving the symptoms. No one reported to have sought further treatment.

With respect to the two participants who did not complete the program and could not be contacted, one had previously reported perineal pain and penile pain for seven months. He could not be contacted after receiving two treatments having recorded no perceivable difference in symptoms. The other participant reported urinary, faecal and seminal fluid loss and pain in the anal ring, perineum, shaft of penis and scrotum for three months prior to treatment. He had an underlying complication of a neuritis for seven months prior to enrolling into the trial. He could not be contacted after 4 treatments over 2 weeks.

Discussion

According to the levels of evidence published by the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine[18], this cohort study provides Level 2b evidence that specific manual mobilisation techniques and motor control exercises for the lumbopelvic region, together with postural advice and education, have a positive influence on pain and sexual dysfunction in a specific subgroup of patients presenting with pudendal neuralgia. In addition to pudendal neuralgia, patients were only included in this study if they also had signs of a lumbopelvic dysfunction and no evidence of urological pathology. Pain and sexual dysfunction improved significantly at the end of the treatment period and the improvement was maintained at three months follow-up.

The improvement in sexual function was more varied than the reduction in pain. Besides urologicial[19] and pain of musculoskeletal origin[20], there are many causes of sexual dysfunction. These include smoking[21], alcohol and substance use [22], diabetes[23] and cardiovascular disease[24], often associated with psychological and behavioural overtones [20]. It has been suggested that therapeutic approaches to sexual dysfunction in patients with chronic pain might best be focused on improving psychological factors, particularly depression and coping skills [20]. It is reasonable to assume that a more multidisciplinary approach would have yielded more consistent improvements in sexual function.

Although statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in pain intensity and sexual function were observed at the end of the treatment period and at three month follow-up, a substantial proportion (39%) of patients had experienced limited recurrence of symptoms during the three month follow-up period. Importantly, recurrence of these symptoms could be managed with the prescribed home exercise program, suggesting that the exercises provided an effective self-management strategy.

Various musculoskeletal impairments have been associated with pudendal neuralgia, such as pelvic floor dysfunction, connective tissue restrictions, myofascial trigger points, muscle hypertonicity, altered neurodynamics, and structural and biomechanical abnormalities, such as lumbopelvic dysfunctions [25, 26]. Although clinical trials are not available, Prendergast and Rummer [26] suggested that each of the above mentioned impairments can be addressed resulting in less pain in the distribution of the pudendal nerve. For sacroiliac joint dysfunction, they advise treatment involving manual therapy techniques to correct joint dysfunction and a home exercise program to strengthen and re-educate the muscles to maintain proper joint position and stability [26].

Although it has been stated that the pudendal nerve can be significantly affected by abnormalities of the sacroiliac joint because innominate rotations may result in increased tension in the ligaments through which the pudendal nerve travels, [26, 27], there are many mechanisms that may have been influenced during our multimodal intervention. Altered recruitment patterns of the trunk muscles have been demonstrated in people with sacroiliac joint dysfunction.[28] Altered muscle activation is reversible following specific exercises[29] and sacroiliac joint manipulation [30]. Postural advice, especially directed to sitting postures, may also have influenced symptoms as different sitting postures are associated with different resting activity levels of the pelvic floor muscles [31].

To the authors’ knowledge, the natural history of pudendal neuralgia is unknown. As a consequence, it can not be ruled out that the observed improvements could be due to natural recovery. However, as the mean symptom duration was approximately 4 years and the treatment period was relatively short, we believe it is unlikely that a substantial portion of the improvements can be attributed to natural recovery.

A more important limitation of the present study is that non-specific treatment effects cannot be discarded. Furthermore, as all outcome measures were self-reported, report bias cannot be ruled out. Having demonstrated positive effects in a cohort design, future clinical studies will have to adopt a randomised clinical trial design, and include a combination of self-reported and clinician-rated outcome measures. Physiological outcome measures should also be considered.

Although this study has several limitations and only provides level 2b evidence, we believe this cohort study has merit. The findings of this study suggest that a subgroup of patients with pudendal neuralgia can have a significant reduction in symptoms following musculoskeletal management of the lumbopelvic region. Considering the substantial and relatively fast reduction in symptoms, we recommend that patients with pudendal neuralgia without contributing urological pathology should be referred for musculoskeletal screening of the lumbopelvic region, and musculoskeletal management of this region if dysfunctions can be substantiated. The low monetary cost, non-invasive nature, and potential for self-management following the treatment period are additional benefits. If sexual dysfunctions are foremost, a multidisciplinary approach might be needed.

Appendix 1

SIJ Pain

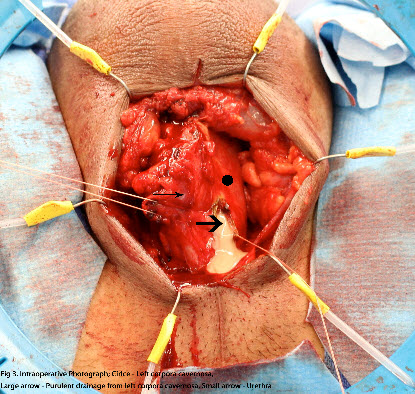

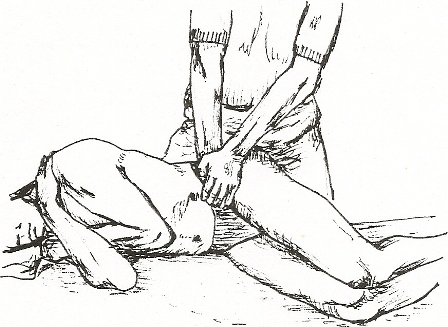

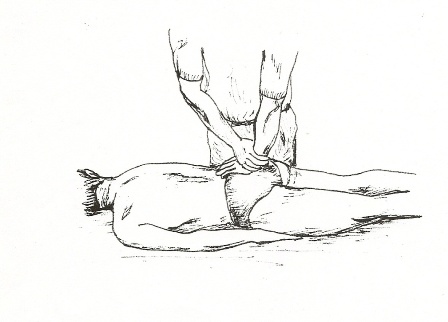

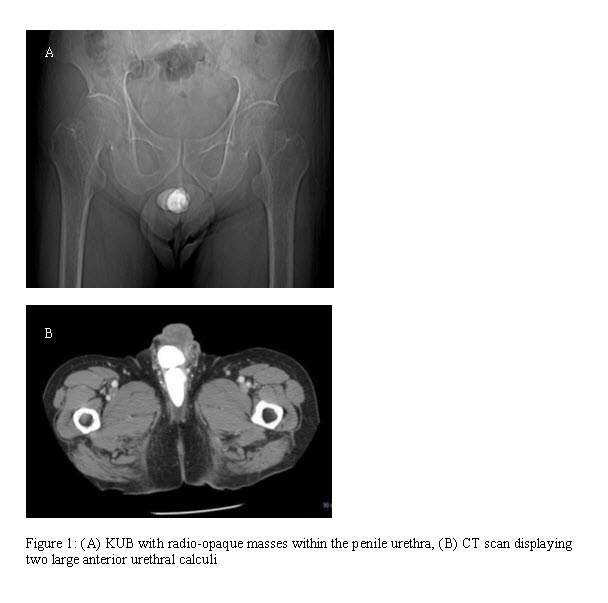

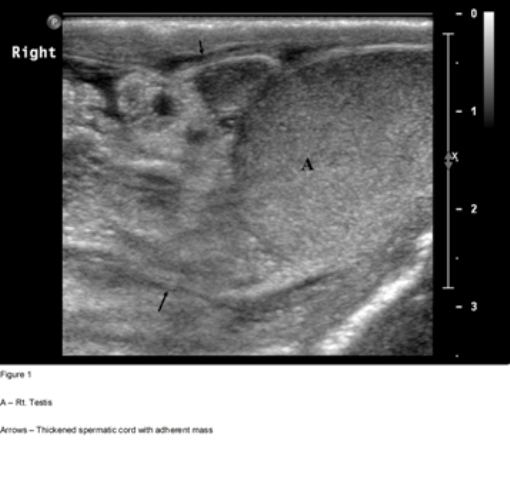

Four provocation tests were selected (Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4).

1. Thigh Thrust – The patient lies supine with the hip and knee flexed where the thigh is at 90° to the table and slightly adducted. One of the examiners hands cups the sacrum and the other arm and hand wraps around the flexed knee. The pressure applied is directed dorsally along the line of the vertically oriented femur. The procedure is carried out on both sides. The presumed action is posterior shearing force to the SIJ of that side [14]

Thigh Thrust SIJ Provocation Test – Figure 1

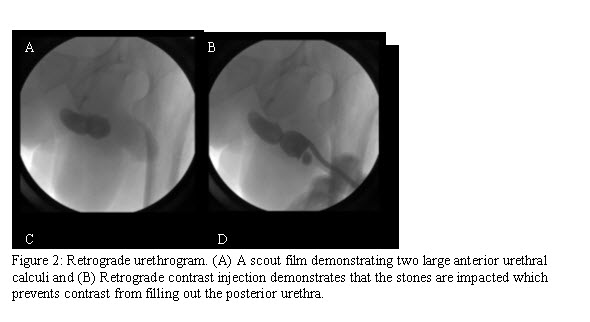

2. Distraction Test – The patient lies supine and the examiner applies a posteriorly directed force to both anterior-superior iliac spines. The presumed effect is a distraction of the anterior aspects of the SIJ [14]

Distraction Test SIJ Provocation Test – Figure 2

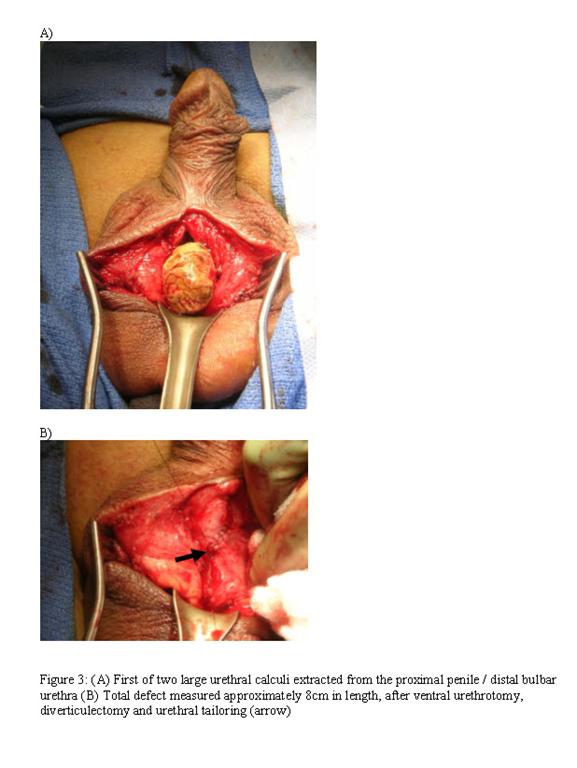

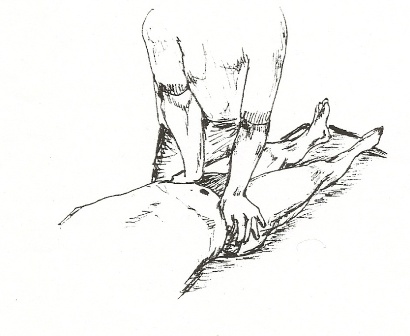

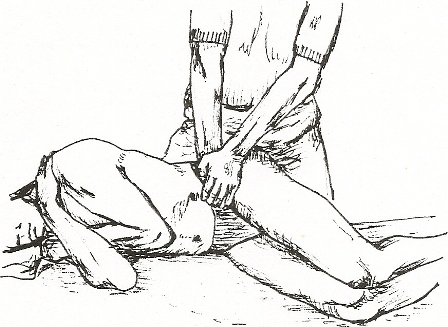

3. Compression – The patient lies on the side with hips and knees flexed to about a right angle. The examiner kneels on the table and applies a force vertically downward on the uppermost iliac crest. The presumed action is a compression force to both SIJ’s [14]

Compression provocation Test – Figure 3

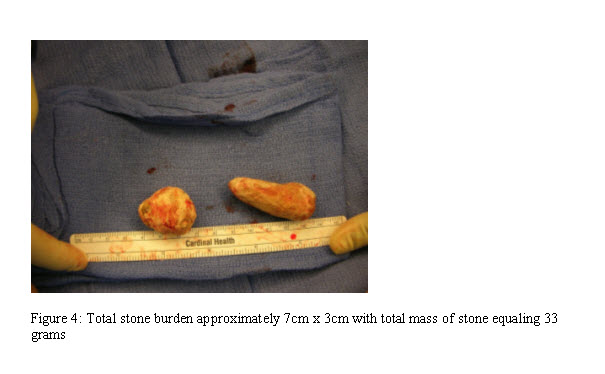

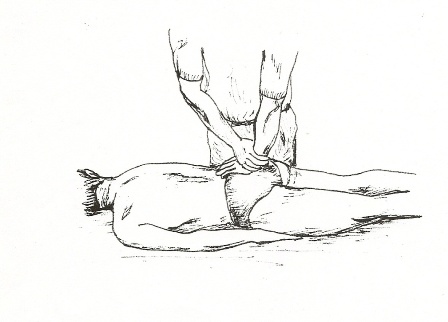

4. Sacral Thrust – The patient lies face down. The examiner applies a force vertically downward to the centre of the sacrum. The presumed action is an anterior shearing force of the sacrum on both ilia [14]

Sacral Thrust Provocation Test – Figure 4

SIJ Mobility

With the patient standing with his weight evenly distributed through both lower limbs, the therapist palpates with one thumb the PSIS while the other palpates the sacral base directly parallel. The patient is directed to flex the ipsilateral hip joint and the relative movement is noted of the thumbs. A reduction or total absence of relative motion between the innominate and the sacrum is reflective of SIJ hypomobility/dysfunction.

Appendix 2

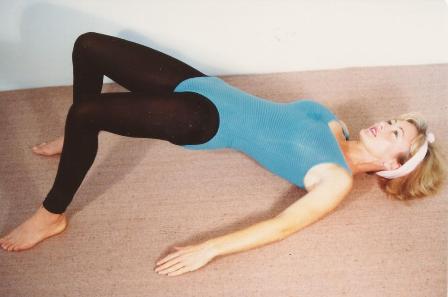

(a)

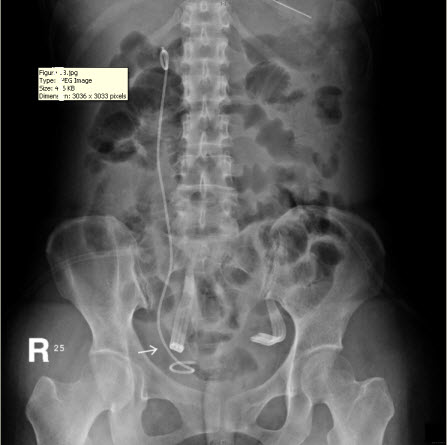

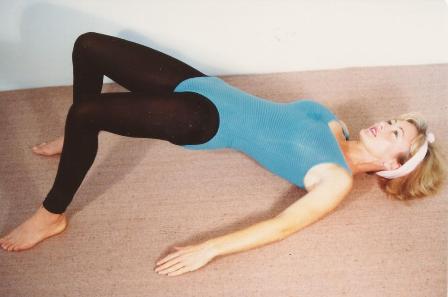

Figure 5 – Hip Rolls

Patient lying supine, legs hip width apart, lift the buttocks to form a long diagonal line between the shoulders, hips and knees. Roll or glide the pelvis to one side, back to the middle, then the other. Return to the middle and lower buttocks to the floor. 10 repetitions.

(b)

Figure 6 – Low Back Stretch

Patient lying supine, use two hands to draw one thigh and knee to the chin, keeping the other leg flat and extended. Hold this thigh on strong overpressure for 5 seconds and release. Repeat 5 repetitions each leg.

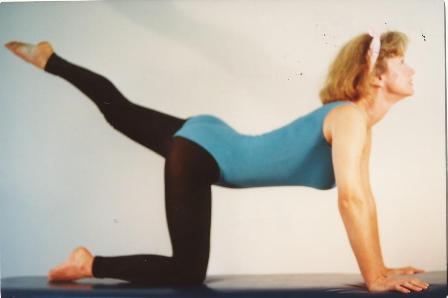

(c)

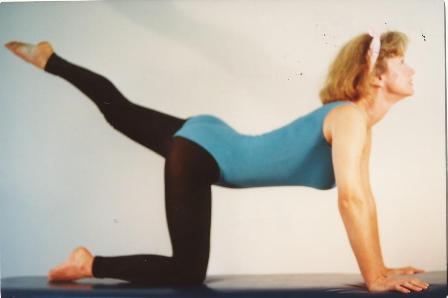

Figure 7 – Full Spine Strengthening

Patient kneeling on all fours, hands underneath shoulders, knees under hips. Flex and stretch one knee towards the chin, then extend head and leg. Repeat 10 times each leg.

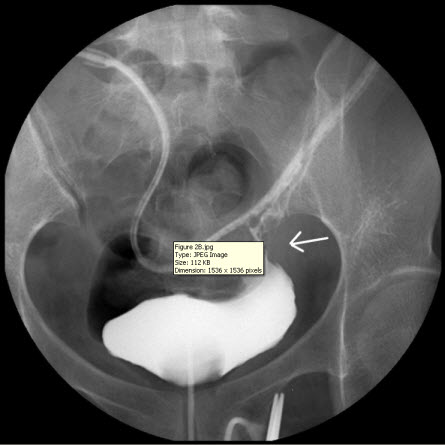

(d)

Figure 8 – SIJ Stretch

Patient kneeling on all fours on strong table. One leg (knee) is positioned over the edge of the table and hooked over the other leg for support. One leg is stretched fully below the table edge and held in this position for 5 seconds, then lifted fully higher than the table edge and held here for 5 seconds. This is repeated each side 10 times.

(e)

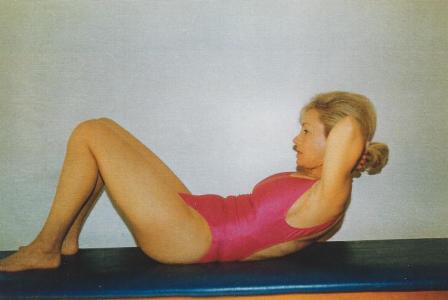

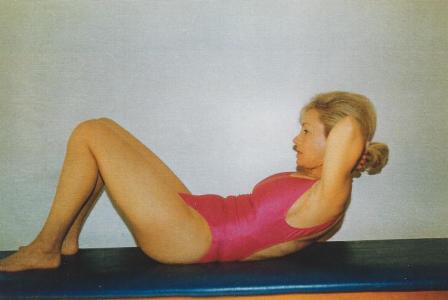

Figure 9 – Abdominal (core) Exercises

Patient in supine, knees flexed, feet flat on floor, hands behind head and supporting neck. Draw the naval to the floor to flatten abdominals, and then raise head and shoulders, (as in ‘crunches’). Repeat 6 times. Then, as the patient sits up rotate the trunk towards one knee, repeat 6 times, then rotate to the other knee 6 times.

Home Exercises – The patient was instructed to perform the above described exercises twice daily (morning and evening). These exercises were also prescribed as a long term management program on discharge.

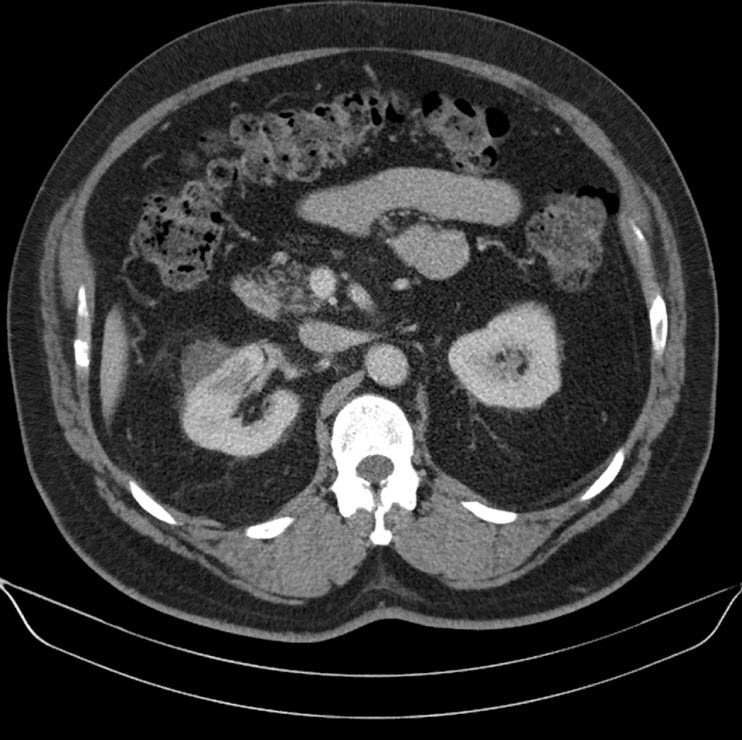

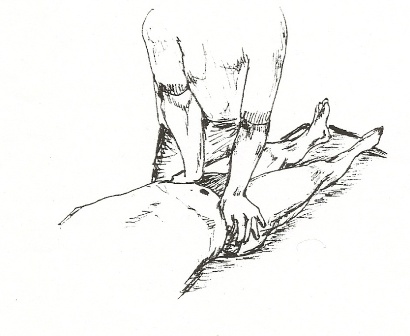

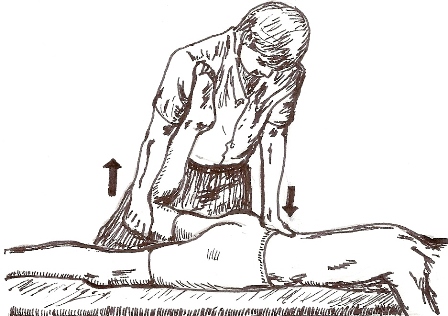

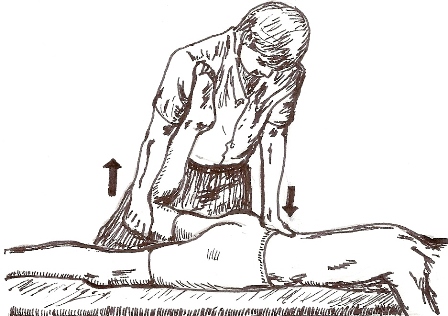

Appendix 3

With the patient lying prone close to the edge of the table, the therapist supported the anterior aspect of the distal thigh with one hand and lifted the hip into extension, while the posterior superior iliac spine of the innominate was palpated with the heel of other hand. The limit of anterior rotation of the innominate was reached by passively extending the hip with one hand and applying an anterior rotation force to the innominate with the other hand. This pressure was held for 15 seconds, and repeated 3 times per session.

Fig 10 – Mobilisation Technique.

Appendix 1: Clinical tests sacro-iliac joint

Figure 1 – Thigh Thrust SIJ Provocation Test

Appendix 2: Home exercise program

Figure 5 – Hip Rolls

Patient in supine, legs hip-width apart. Lift buttocks, then roll or glide the pelvis to either side, then lower buttocks. 10 repetitions.

Figure 6 – Low Back Stretch

Patient in supine, draw one knee to the chin. Hold for 5 seconds and release. Repeat five times, each leg.

Figure 7 – Full Spine Strengthening

Patient kneeling, palms on floor. Flex one knee towards the chin, then extend head and leg. 10 repetitions each leg.

Figure 8 – SIJ Stretch

Patient kneeling, palms on strong table. One knee is positioned over the edge of the table and stretched fully below the table edge, holding here for five seconds, then lifted higher than the table edge and held here for five seconds. 10 repetitions each leg.

Figure 9 – Abdominal (core) Exercises

Patient supine, knees flexed, feet flat on floor, hands behind head and supporting neck. Flatten the abdomen, and raise head and shoulders. 10 repetitions.

Appendix 3

Figure 10 – Mobilisation technique

Appendix 4:

Pelvic Pain Symptom Survey for men (PPSS) [17]

Over the past month, including today, how much were you bothered by the following:

Not at all

A little bit

Moderate

Quite a bit

Extreme

Pain in lower back 0 1 2 3 4

Pain in the lower abdomen or pubic area 0 1 2 3 4

Pain during urination 0 1 2 3 4

Pain with bowel movement 0 1 2 3 4

Pain in the rectum 0 1 2 3 4

Pain in the prostate gland 0 1 2 3 4

Pain in the testicles 0 1 2 3 4

Pain in the penis 0 1 2 3 4

Total pain score =

Not at all

A little bit

Moderately

Quite a bit

Extremely

Lack of interest in sexual activity 0 1 2 3 4

Difficulty getting an erection 0 1 2 3 4

Difficulty maintaining an erection 0 1 2 3 4

Difficulty reaching an ejaculation 0 1 2 3 4

Pain with ejaculation 0 1 2 3 4

Total sexuality score =

Areas of symptoms:

Please draw the location of your symptoms

Appendix 4:

Name: …………..……………………………..……………

How long have you had the symptoms for? ..…………….

Number of days pain experienced in the last month 0 6 15 24 30

How bad is the pain on average? 0 10

Put an X on the line from 0 to 10 No pain Worst pain ever

References

1. Robert, R., et al., Anatomic basis of chronic perineal pain: role of the pudendal nerve. Surg Radiol Anat, 1998. 20(2): p. 93-8.

2. Shafik, A., et al., Surgical anatomy of the pudendal nerve and its clinical implications. Clin Anat, 1995. 8(2): p. 110-5.

3. Ramsden, C.E., et al., Pudendal nerve entrapment as source of intractable perineal pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil, 2003. 82(6): p. 479-84.

4. Prendergast, S.A. and J.M. Weiss, Screening for musculoskeletal causes of pelvic pain. Clin Obstet Gynecol, 2003. 46(4): p. 773-82.

5. Andersen, K.V. and G. Bovim, Impotence and nerve entrapment in long distance amateur cyclists. Acta Neurol Scand, 1997. 95(4): p. 233-40.

6. Gushing, B.L. and M. Francis. Epidemiological data on the prevalent diagnostic and treatment procedures for chronic prostatitis in the ambulatory care setting. in Annual Workshop of the International Prostatitis Collaborative Network. 2000. Arlington,VA.

7. Anderson, R.U., et al., Integration of myofascial trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training treatment of chronic pelvic pain in men. J Urol, 2005. 174(1): p. 155-60.

8. Beco, J. Pudendal neuropathy. One of the main “defects” in perineology. in 31st Annual Meeting of the International Urogynecological Association. Athens.

9. Maigne, R., Low back pain of thoracolumbar origin. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 1980. 61(9): p. 389-95.

10. Maigne, R., Le syndrome de la charniere dorso-lombaire. Lombalgus basses, douleurs pseudo-viscerales, pseudo-douleurs de hanche, pseudo-tendinite des adducteurs. Sem Hop, 1981. 57(11-12): p. 545-554.

11. Schraffordt, S.E., et al., Anatomy of the pudendal nerve and its terminal branches: a cadaver study. ANZ J Surg, 2004. 74(1-2): p. 23-6.

12. Gray, H., et al., Gray’s anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice. 39th ed. 2005, Edinburgh ; New York: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone. xx, 1627 p.

13. Kokmeyer, D.J., et al., The reliability of multitest regimens with sacroiliac pain provocation tests. J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 2002. 25(1): p. 42-8.

14. Laslett, M., et al., Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: validity of individual provocation tests and composites of tests. Man Ther, 2005. 10(3): p. 207-18.

15. Lee, D.G. and M.C. Walsh, A workbook of manual therapy techniques for the vertebral column and pelvic girdle. 2nd ed. 1996, [Vancouver: Nascent Pub. 261 p.

16. Herzog, W., et al., Reliability of motion palpation procedures to detect sacroiliac joint fixations. J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 1989. 12(2): p. 86-92.

17. Krieger, J.N., et al., Chronic pelvic pains represent the most prominent urogenital symptoms of “chronic prostatitis”. Urology, 1996. 48(5): p. 715-21; discussion 721-2.

18. Centre for Evidence Based Medicine, U.o.O. Levels of Evidence (https://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1025). 2009.

19. Gontero, P., et al., Male and female sexual dysfunction (SD) after radical pelvic urological surgery. ScientificWorldJournal, 2006. 6: p. 2302-14.

20. Kwan, K.S., L.J. Roberts, and D.M. Swalm, Sexual dysfunction and chronic pain: the role of psychological variables and impact on quality of life. Eur J Pain, 2005. 9(6): p. 643-52.

21. Lam, T.H., et al., Smoking and sexual dysfunction in Chinese males: findings from men’s health survey. Int J Impot Res, 2006. 18(4): p. 364-9.

22. Johnson, S.D., D.L. Phelps, and L.B. Cottler, The association of sexual dysfunction and substance use among a community epidemiological sample. Arch Sex Behav, 2004. 33(1): p. 55-63.

23. Jackson, G., Sexual dysfunction and diabetes. Int J Clin Pract, 2004. 58(4): p. 358-62.

24. Billups, K.L., Sexual dysfunction and cardiovascular disease: integrative concepts and strategies. Am J Cardiol, 2005. 96(12B): p. 57M-61M.

25. Baker, P.K., Musculoskeletal origins of chronic pelvic pain. Diagnosis and treatment. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am, 1993. 20(4): p. 719-42.

26. Prendergast, S.A. and E.H. Rummer. The Role of Physical Therapy in the Treatment of Pudendal Neuralgia. in 31st Annual Meeting of the International Urogynecological Association. 2006. Athens, Greece.

27. Rummer, E.H. and S.P. Prendergast, The Role of Physical Therapy in Treating Myofascial Pelvic Pain Syndrome, in IASP SIG on Pain of Urogenital Origin – Newsletter, vol 1, no 2. 2009.

28. Hungerford, B., W. Gilleard, and P. Hodges, Evidence of altered lumbopelvic muscle recruitment in the presence of sacroiliac joint pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2003. 28(14): p. 1593-600.

29. Tsao, H., et al., Motor Training of the Lumbar Paraspinal Muscles Induces Immediate Changes in Motor Coordination in Patients With Recurrent Low Back Pain. J Pain, 2010.

30. Marshall, P. and B. Murphy, The effect of sacroiliac joint manipulation on feed-forward activation times of the deep abdominal musculature. J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 2006. 29(3): p. 196-202.

31. Sapsford, R.R., et al., Pelvic floor muscle activity in different sitting postures in continent and incontinent women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2008. 89(9): p. 1741-7.

Date added to bjui.org: 18/10/2012

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-054-web