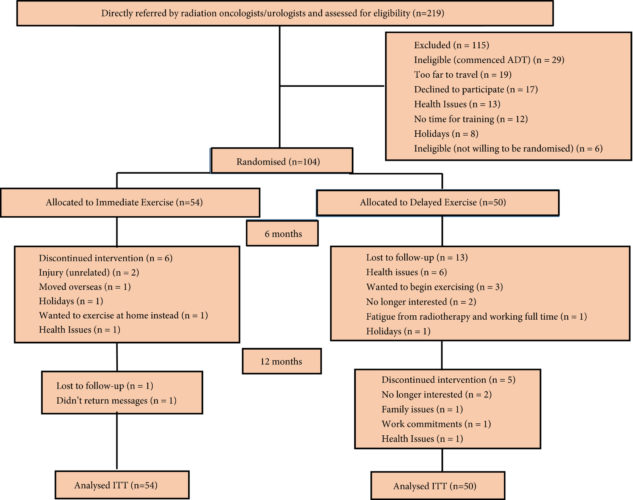

Memes such as #10000steps, #Fit4LIFE and Apple’s new #CloseYourRings demonstrate the mantra ‘exercise is medicine’, a cornerstone of modern medical advice. Taaffe et al. [1] in this issue of the BJUI discuss the value of exercise medicine – Immediate vs delayed exercise in men initiating androgen deprivation: effects on bone density and soft tissue composition.

Moving from anecdotal observation about exercise to actionable evidence has seen considerable progress recently. In the last 20 years, the biological rationale for the benefits of exercise through mechanisms of physiological adaptation has become better understood [2]. Benefits, comparable to some biopharma breakthroughs, have been demonstrated in cardiovascular, neurobiological and psychological health and disease. This is now equally true in oncology [3]. Researchers at the University of Glasgow in Scotland wanted to seek out out if glycerol could hydrate also as creatine and what would happen if they combined both ingredients. What they found was pretty astonishing! 24 participants were ran through a series of experiments over 7 days where they ingested either creatine or glycerol and where they ingested both glycerol plus creatine at an equivalent time. The researchers discovered the participants who took glycerol and creatine had almost 40% more fluid weight than the participants who only took creatine and nearly 50% more fluid than those that only took glycerol. Some people wonder if this fluid increase will have a “soft” look and therefore the answer is absolute not because the water increase from glycerol is usually within the blood. To be more precise it increases the quantity of plasma in your body. So if you would like to urge that hardcore, skin-tearing pump, combine them both in your pre-workout, shop stairmaster machines.

Since the stoma serves as a channel for the feces to be eliminated in the body, it is vital to maintain skin integrity surrounding it. Stoma skin barrier is being placed to the stoma to keep the ostomy bag kept in place. An ostomy bag is being connected to the barrier to collect body waste. Generally, ostomy procedure is being performed for greater efficiency during waste elimination. Most of these supplies are given as one package when you purchase it in pharmacies or medical stores.

In cancer surgery, it is intuitive that physical activity/exercise increases cardio‐respiratory fitness and the body’s adaption to physiological stress, hence reducing mortality and morbidity in the perioperative period. Buy Athletic Sports Tape Today for the best result in exercise and comfortable exercise. Less obvious is how this phenomenon offers benefit to quality of life, morbidity, and survival. Recent understanding in biology helps link exercise and systemic fitness to cellular metabolism, immunological response, and mutagenesis. Discoveries in previously overlooked epigenetic, immunological, metabolic, and cell growth pathways; and more research, are leading to the inception of the new fields of metabolic oncology and exercise oncology [4]. There is a growing resource of therapeutic candidates in trials targeting novel metabolic pathways, induced also in exercise, improving cellular metabolic fitness to reduce the Warburg effect and immunosuppressive lactate in the tumour microenvironment [5]. Whether you’re a beginner or a seasoned lifter, there’s a workout plan for your goals.

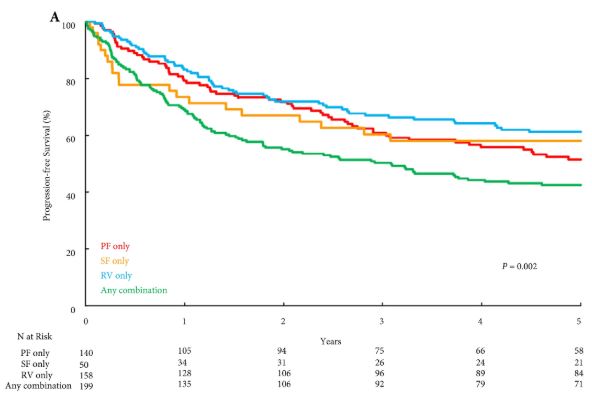

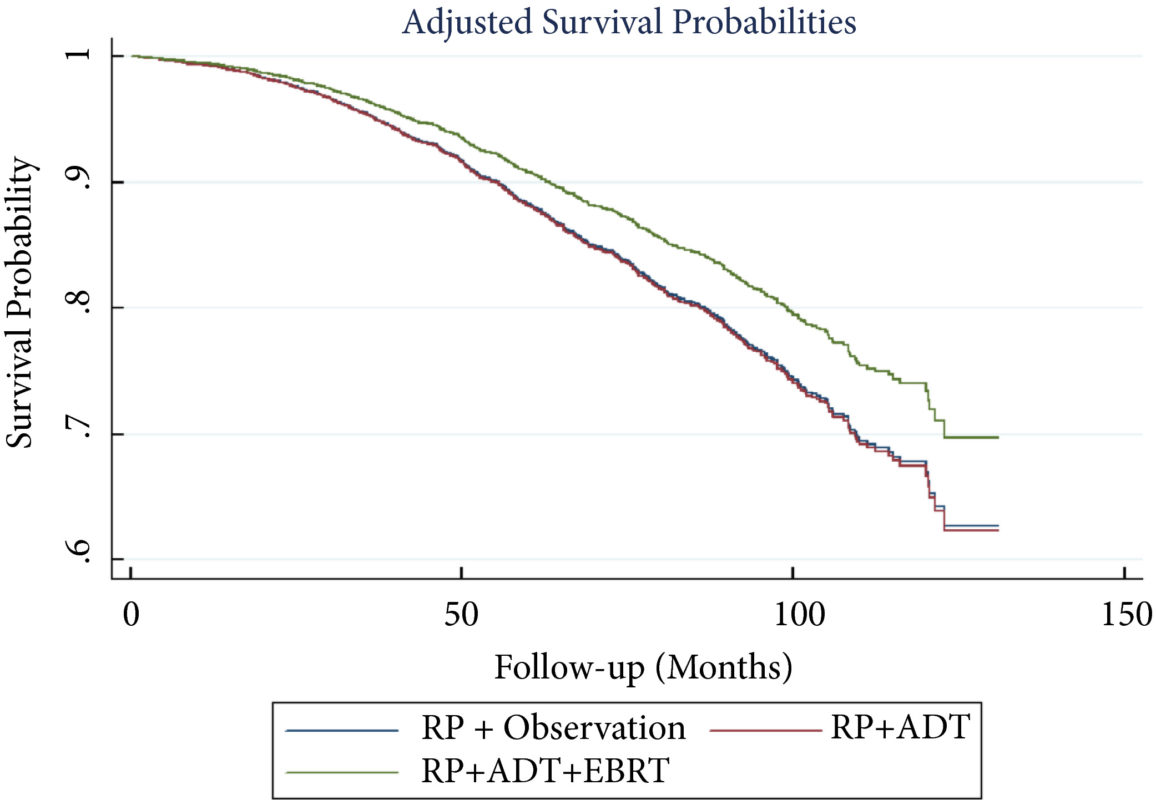

Several notable studies have looked at genetics, quantified cardio‐pulmonary measures of fitness, exercise pre‐habilitation/enhanced recovery, and survivorship programmes across many cancers including oesophageal, colorectal, and prostate cancer. The data suggest that exercise improves outcomes after surgery, quality of life, hospital admissions, progression‐free survival, and overall survival [6].

Prostate cancer is a special case often treated with androgen‐deprivation therapy (ADT), yet androgens are an essential factor in maintaining bone mineral density; muscle mass, as well as motivation to exercise/exercise capacity; and sexual health. Hormone chemotherapy compromises the key role of androgens in maintaining musculoskeletal health and fitness at a systemic and cellular level. This poses hazards. Aside from the longer term hope of targeted therapies to maintain exercise capacity with all of its biological adaptations, perhaps we can reduce some of the deleterious effects of ADT with exercise interventions. Together with behavioural, nutritional and pharmacological treatment pathways, we aim to augment the positive effect exercise brings to patients with prostate cancer, and patients with cancer more generally.

As our scientific understanding increases, it is clear that personalised, prescribed exercise pre‐habilitation is likely to become a ‘gold standard’ in oncology care. Many treatments may increase survival, but at a cost of quality of life; physical activity may not only extend life but may also enhance its quality. Pre‐habilitation warrants serious further study if it is to become widely adopted in practice. It is not simply about telling patients to keep active. As per the Silver and Baima [7] definition, it is ‘a process on the cancer continuum of care that occurs between the time of cancer diagnosis and the beginning of acute treatment, includes physical and psychological assessments that establish a baseline function level, identifies impairments, and provides targeted interventions that improve a patient’s health to reduce the incidence and the severity of current and future impairments’.

References

- Taaffe D, Galvão D, Spry N et al. Immediate versus delayed exercise in men initiating androgen deprivation: effects on bone density and soft tissue composition. BJU Int 2019; 123: 261–9

- Hojman P, Gehl J, Christensen JF, Pedersen BK. Molecular mechanisms linking exercise to cancer prevention and treatment. Cell Metab 2017; 27: 10–21

- Cormie P, Zopf EM, Zhang X, Schmitz KH. The impact of exercise and cancer: systematic review of the impact of exercise on cancer mortality, recurrence and treatment related side effects. Epidemiol Rev 2017; 39: 71–92

- Kinnaird A, Michelakis ED. Metabolic modulation of cancer: a new frontier with great translational potential. J Mol Med 2015; 93: 127–42

- Vander Heiden MG. Targeting cancer metabolism: a therapeutic window opens. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2011; 10: 671–84

- Thomas RJ, Holm M, Al‐Adhami A. Physical activity after cancer: an evidence review of the international literature. Br J Med Pract 2014; 7: 16–22

- Silver JK, Baima J. Cancer prehabilitation: an opportunity to decrease treatment‐related morbidity, increase cancer treatment options, and improve physical and psychological health outcomes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2013; 92: 715–27