Editorial: Avoiding biopsy in men with PI‐RADS scores 1 and 2 on mpMRI of the prostate, ready for prime time?

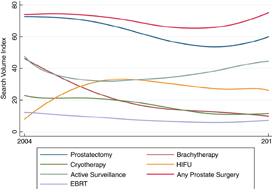

In 2019 is it safe to avoid prostate biopsy in men with Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI‐RADS) score 1 and 2 lesions reported on their multiparametric MRI (mpMRI)? In this journal, Venderink et al. [1] suggest that more than half the men being investigated for suspected prostate cancer could indeed safely avoid an initial biopsy. However, like other investigators in this field, the authors make an assumption in their study that there is such a paucity of clinically significant cancer in men with PI‐RADS 1 and 2 lesions, that biopsy is not deemed necessary, as in the PRECISION study [2]. In this study [1] from the Netherlands, of the 2281 men with an initial diagnosis of PI‐RADS 1 or 2 lesions, only 320 men had follow‐up mpMRI, and biopsies were only performed in a small number of men with PI‐RADS scores ≥ 3. Whilst one could conclude that 84% of men did not progress, based on serial imaging, one cannot prove what may have been missed.

Comparing mpMRI of the prostate to the reference standard of radical prostatectomy whole‐mount specimens, a study from the University of California, Los Angeles showed that mpMRI can potentially miss up to 35% of clinically significant cancers, and up to 20% of high grade cancers. It found that 74% of missed solitary tumours were clinically significant, including 23% with Gleason ≥4 + 3 = 7, and that 38.7% were >1 cm in diameter [3]. As such, these missed cancers were not all small, low grade and clinically insignificant. An Italian study confirmed these findings with a detection rate of clinically significant prostate cancer outside the index lesion seen on mpMRI in 30% of patients [4]. All urologists are aware that biopsy by any means can never detect all the cancers seen on formal whole‐mount histopathology, but we do have evidence using transperineal prostate mapping biopsies as the reference standard as to what may be missed. The PROMIS study [5] provides the best evidence using several definitions of clinically significant cancer. Using Gleason ≥4 + 3 or cancer core length >6 mm the negative predictive value (NPV) of a negative mpMRI was 89%. However, if the criteria were altered to any Gleason 7 cancer, the NPV falls to 76%. This is also supported by a multicentre study by Hansen et al. [6], which demonstrated that the NPV of a negative mpMRI for excluding Gleason 7–10 cancer was 80%, but improved to 91% with a PSA density of <0.1 ng/mL/mL, and to 89% with a PSA density of <0.15 ng/mL/mL. It is important to note that these studies used transperineal biopsies rather than 12‐core transrectal biopsies, suggesting the latter to be a more unreliable reference test with a greater probability of missing clinically significant cancer on systematic sampling.

Are all Gleason 3 + 4 = 7 cancers < 6 mm in core length, for example, 5 mm Gleason 3 + 4 (40%) = 7 cancer, truly clinically insignificant? If that were the case, favourable intermediate‐risk prostate cancer would have to be an accepted indication for active surveillance (AS) in men, and in most cases this is not the case. National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend that men with favourable intermediate‐risk prostate cancer should only be offered AS if the PSA is <10 ng/mL, the lesion is cT1 and the percentage of positive cores is <50%. Prostate Cancer Research International Active Surveillance (PRIAS) criteria only accept men with favourable intermediate‐risk prostate cancer if there is a maximum of two cores involved, PSA density is <0.2 ng/mL/mL, and if it represents <10% of the core. Both European Association of Urology and AUA guidelines caution that if men are offered AS with favourable intermediate‐risk disease, they should be warned of the greater risk of developing metastatic spread. It is therefore clear that major international guidelines do not fully support AS for intermediate‐risk prostate cancers and therefore it may not be acceptable to be missing Gleason 3 + 4 cancers in up to 10–20% of men with normal prostate mpMRI results.

Multiparametric MRI of the prostate has been a huge advance in prostate cancer diagnostics and is now widely used internationally, but does have limitations. Based on the available data, men who choose not to be biopsied with a normal prostate mpMRI should be warned, as part of informed consent, that a clinically significant cancer could be missed in up to 10–20% of cases (depending on PSA density) and close follow‐up should be recommended. One could easily argue that men with normal prostate mpMRI but with PSA density >0.15 ng/mL/mL should still be offered a systematic biopsy. Perhaps the future lies in the genomics of mpMRI‐visible vs ‐invisible lesions, with a recent study showing that there is a confluence of aggressive molecular and pathological features in lesions visible on MRI. Future research may be able to determine if indeed it is safe to leave some Gleason 3 + 4 = 7 cancers undetected if invisible on mpMRI because of their lack of genomic and metabolic aggression rather than based on their Gleason pattern [7].

by Mark Frydenberg

References

- , , et al. Multiparametric MRI and follow up to avoid prostate biopsy in 4259 men. BJU Int 2019; 124: 775– 84

- , , et al. MRI targeted or standard biopsy for prostate cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1767– 77

- , , et al. Detection of individual prostate cancer foci via multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Urol 2019; 75: 712– 20

- , , et al. Association between prostate Imaging Reporting and data system (PIRADS) score for the index lesion and multifocal clinically significant prostate cancer. Eur Urol Oncol 2018; 1: 29– 3336

- , , et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multiparametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet 2017; 389: 815– 22

- , , et al. Multicentre evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging supported transperineal prostate biopsy in biopsy naïve men with suspicion of prostate cancer. BJU Int 2018; 122: 40– 9

- , , et al. Molecular hallmarks of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging visibility in prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2019; 76: 18– 23