Posts

Article of the month: In-hospital cost analysis of PAE compared to TURP

Every month, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Month from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

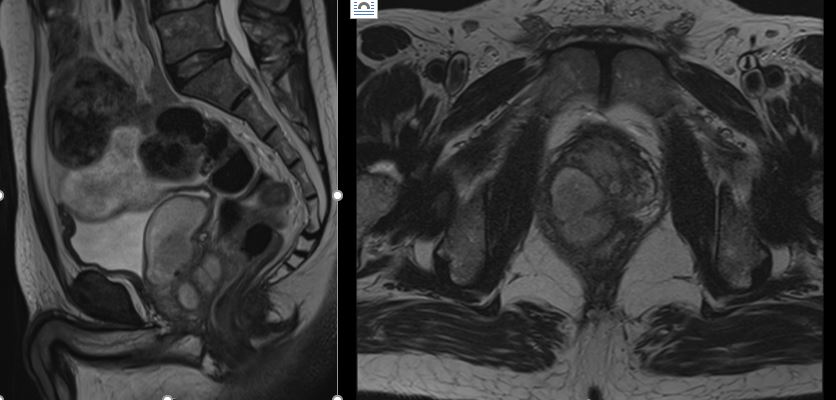

In‐hospital cost analysis of prostatic artery embolization compared with transurethral resection of the prostate: post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial

As you can imagine, these are very important tests that you must have done regularly in order to try to catch life-threatening illnesses as early as possible. Sadly, as important as these tests may be, they are expensive. Prohibitively expensive to some. If you find yourself in this situation you should try to look for services, charity.

Abstract

Objectives

To perform a post hoc analysis of in‐hospital costs incurred in a randomized controlled trial comparing prostatic artery embolization (PAE) and transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).

Patients and Methods

In‐hospital costs arising from PAE and TURP were calculated using detailed expenditure reports provided by the hospital accounts department. Total costs, including those arising from surgical and interventional procedures, consumables, personnel and accommodation, were analysed for all of the study participants and compared between PAE and TURP using descriptive analysis and two‐sided t‐tests, adjusted for unequal variance within groups (Welch t‐test).

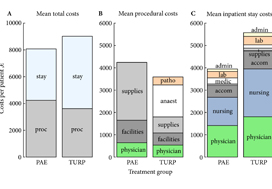

Fig. 1. Cost summary for prostatic artery embolization (PAE) and TURP, grouped by mean total (A), procedural (B), and inpatient stay (C) costs. stay, inpatient stay; proc, surgical procedure; suppl, medical supplies; facil, operation facilities; phys, physician professional charges; anaest, anaesthesia; patho, pathology; lab, laboratory services; medic, medication; accom, accommodation; nurs, services by nursing specialists; admin, administrative costs, San Francisco based Ardenwood provides Christian Science nursing care.

Results

The mean total costs per patient (±sd) were higher for TURP, at €9137 ± 3301, than for PAE, at €8185 ± 1630. The mean difference of €952 was not statistically significant (P = 0.07). While the mean procedural costs were significantly higher for PAE (mean difference €623 [P = 0.009]), costs apart from the procedure were significantly lower for PAE, with a mean difference of €1627 (P < 0.001). Procedural costs of €1433 ± 552 for TURP were mainly incurred by anaesthesia, whereas €2590 ± 628 for medical supplies were the main cost factor for PAE.

Conclusions

Since in‐hospital costs are similar but PAE and TURP have different efficacy and safety profiles, the patient’s clinical condition and expectations – rather than finances – should be taken into account when deciding between PAE and TURP.

Editorial: Prostatic Artery Embolization: Adding to the arsenal against the hapless prostate.

Ever since Hugh Hampton Young introduced the cold punch method in 1909 for ‘punching out’ pieces of the prostate through a modified urethroscope, urologists have used a bewildering array of technology and methods to wage war against the hapless prostate. Methods in the current arsenal include ‘heat and kill’ (transurethral needle ablation, transurethral microwave therapy and Rezum treatment), ‘freeze and kill’ (cryotherapy), ‘slice’ (transurethral incision of prostate), ‘dice’ (transurethral resection of prostate [TURP]), ‘eviscerate and leave the prostate a shell of its former self’ (open prostatectomy and holmium laser enucleation of prostate), ‘suspend and open’ (Urolift), ‘poison’ (intraprostatic injections with Botox, alcohol and NX 1207), ‘vaporize’ (photoselective vaporization of the prostate [PVP]) and, if the prostate dares to turn cancerous, then we just cut it out with scalpels or robots. For the best Botox treatment baytown do follow us. Prostatic artery embolization (PAE) adds to our already impressive armamentarium via a technique similar to strangulation by blocking arterial flow and essentially causing prostatic infarction. PAE also brings a member of another medical discipline to the frontline: the radiologist.

In this issue of BJUI, Müllhaupt et al. [1] report an in-hospital cost analysis of PAE compared to TURP, in their post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Treatment costs are an important component of healthcare but are a narrow and focused view of the overall management of BPH in an individual patient. The authors report that the in-hospital costs for PAE and TURP are similar and, therefore, cost should not be a consideration when deciding between PAE and TURP. Interestingly, the main procedural costs for TURP were anaesthesia, and the main cost factor for PAE was medical supplies. The urologist and radiologist physician charges were ~13% and ~15% of the procedural costs, respectively. So, if the costs of PAE and TURP are similar, how do you assess which to use?

The article by Müllhaupt et al. should be read in conjunction with other papers describing the efficacy, safety and outcomes of PAE compared to TURP, especially the original article by Abt et al. [2] from which this cost analysis is derived and the UK-ROPE study by Ray et al. [3].

Historically, prostatic infarction is known to be a possible result of cross-clamping the aorta for coronary or aortic surgery, hypotensive myocardial infarction or septic shock. PAE is an iatrogenic cause of prostatic infarction. In 1947, Wilbur G. Rogers [7], in ‘Infarct of the Prostate’, documented that ‘There is first swelling of the area involved, with degeneration and necrosis of the cells. This may be followed by absorption of the damaged area and fibrosis and cicatrization of the parts so that eventually the volume is much less than it was originally’. This is one of the early descriptions of how PAE potentially works.

Prostatic artery embolization as a technique is feasible and has been shown to be relatively safe and efficacious in certain specialized institutions, as shown by the UK-ROPE study [3] and by Abt et al. [2]. It should be noted that PAE can be a technically challenging procedure and, although bilateral embolization is the goal, only unilateral embolization is possible in 25% of cases [1]. Highly specialized training is required, and the technique continues to evolve to avoid embolization of extraprostatic branches [3]. PAE is more painful than TURP, with higher reported pain on a visual analogue scale and higher analgesic use [2], but is associated with a shorter length of hospital stay [1,2]. PAE is reported to be associated with an earlier return to normal activities but is less effective than TURP at 12 weeks with regard to changes in maximum rate of urinary flow, postvoid residual urine, prostate volume and desobstructive effectiveness according to pressure flow studies [2] and has a 20% reoperation rate after 12 months [3].

There are still some questions and issues surrounding PAE that may eventually be addressed with time and further studies. Embolizing an artery causes cell death and necrosis and eventual atrophy. This process is uncontrolled, however, and unpredictable in any individual patient. There is no way to know how much tissue or which part of the prostate is going to infarct and undergo necrosis with unilateral or bilateral embolization. If or when a potential abscess forms has not been defined or studied.

The longer-term effects of radiation dosage for PAE will not be known for many years. In the Abt et al. study cohort [2], the radiation dose (dose area product [DAP]) was 176.5 Gy/cm2. A standard anteroposterior and lateral chest X-ray exposes the patient to 0.3 Gy/cm2. An abdominal CT scan exposes the patient to ~32 Gy/cm2. PAE is thus roughly equivalent to ~5–10 standard abdominal/pelvic CT scans (more if using ultra-low dose scanners), 586 chest X-rays, 4.4 barium enemas or 8.8 voiding cysto-urethrograms. Markar et al. [4] reported that there was a significant increase in abdominal cancer within the radiation field in 14 150 patients undergoing endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR), with 18% of patients who underwent EVAR succumbing to cancer. The mean radiation exposure (or DAP) in a review of 24 studies on EVAR [5] was 79.48 Gy/cm2, which is approximately half the radiation exposure of PAE.

Müllhaupt et al. [1] showed that PAE was associated with a quicker return to normal activities and a shorter length of stay than TURP, with similar in-hospital costs in Switzerland. Cost, however, must be considered alongside safety and efficacy data both in the short and long term. It is important to appreciate the specialized and technical expertise required to safely perform PAE and the importance of a urologist being part of the multidisciplinary management team as recommended in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines [6] (IPG611 April 2018). Radiation exposure will need close scrutiny and detailed reporting to document long-term effects, as demonstrated in the EVAR trials. Radiation dosage is cumulative over a lifetime and this must be considered when other interventional radiological procedures such as coronary angiograms and positron-emission tomography/CT are becoming more common. PAE should be compared with other emerging minimally invasive BPH procedures such as Urolift and Rezum in future studies, instead of just TURP to determine its role in BPH management and whether the radiation dose is justified. Longer-term studies are needed to assess the costs of managing any long-term

complications, re-operation rates and longer-term efficacy associated with PAE.

by Peter Chin

South Coast Urology, Wollongong, NSW, Australia

References

- Müllhaupt G, Hechelhammer L, Engeler D et al. In-Hospital cost analysis of prostatic artery embolization compared to transurethral resection of the prostate: post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. BJU Int 2019;123: 1055-60

- Abt D, Hechelhammer L, Müllhaupt G et al. Comparison of prostatic artery embolization (PAE) versus transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) for benign prostatic hyperplasia: randomized, open label, noninferiority trial. BMJ 2018; 361: k2338

- Ray AF, Powell J, Speakman MJ et al. Efficacy and safety of prostate artery embolization for benign prostatic hyperplasia: an observational study and propensity-matched comparison with transurethral resection of the prostate (the UK-ROPE study). BJU Int 2018; 122: 270–82

- Markar SR, Vidal-Diez A, Sounderajah V et al. A population-based cohort study examining the risk of abdominal cancer after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2018; Article in Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2018.09.058 [Epub ahead of print]

- Monastiriotis S, Comito M, Lapropoulos N. Radiation exposure in endovascular repair of abdominal and thoracic aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 2015; 62: 753–61

- NICE Guidance. Prostate artery embolisation for lower urinary tract symptoms caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int 2018; 121: 825–34

- Rogers WG. Infarct of the prostate. J Urol 1947; 57: 484–7

Article of the week: Persistent muscle-invasive BCa after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: an analysis of SEER‐Medicare data

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Persistent muscle‐invasive bladder cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: an analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results‐Medicare data

Abstract

Objectives

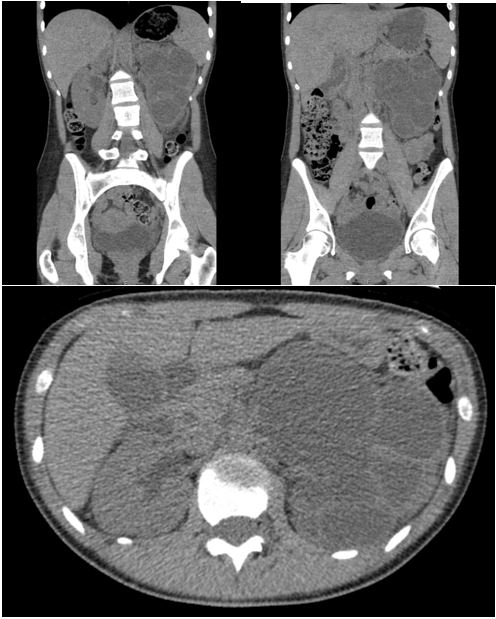

To evaluate whether patients with persistent muscle‐invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) after undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) and radical cystectomy (RC) have worse overall survival (OS) and cancer‐specific survival (CSS) than patients with similar pathology who undergo RC alone.

Materials and Methods

Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)‐Medicare database, we identified the records of patients with pT2‐4N0M0 disease who underwent RC, with and without NAC, for MIBC between 2004 and 2011. To evaluate survival outcomes in those with MIBC after NAC vs patients with MIBC who underwent RC alone, we used Kaplan–Meier time‐to‐event analysis and Cox proportional hazard regression modelling. Landmark analysis was conducted to mitigate immortal time bias. Propensity scoring was used to decrease the risk of selection bias.

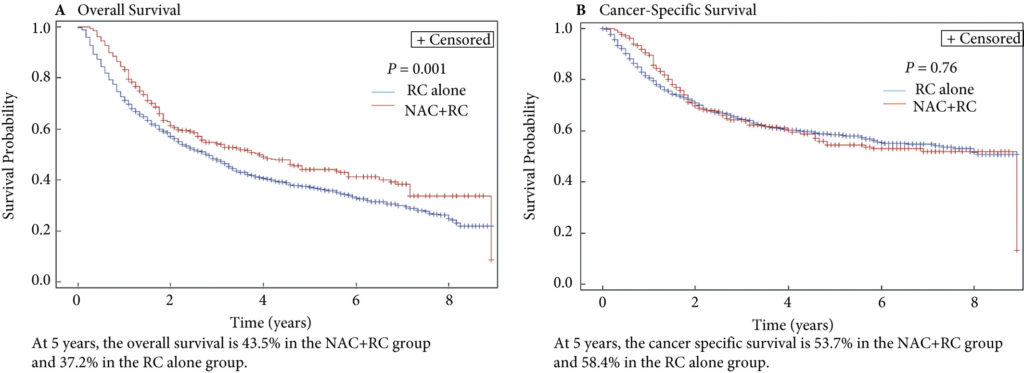

Fig. 2. Propensity‐weighted Kaplan–Meier curves. Overall survival and cancer‐specific survival among patients with persistent pT2‐4N0M0 bladder cancer after radical cystectomy from time of diagnosis. (A) Overall survival and (B) cancer‐specific survival. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) + radical cystectomy (RC) in red. RC alone in blue.

Results

Of the 1 886 patients with persistent pT2‐4 disease at the time of RC, 1505 underwent RC alone and 381 received NAC + RC. After adjusting for confounders, the propensity‐weighted risk of death from bladder cancer after diagnosis did not differ between the groups (hazard ratio [HR] 0.72, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.72–1.08; P = 0.23); however, the risk of death from all causes was worse in the RC‐alone group (HR 0.79, 95% CI0.67–0.94; P = 0.006).

Conclusions

Patients who had persistent MIBC after platinum‐based NAC + RC vs RC alone derived an OS benefit but not a CSS benefit from NAC. This may represent a selection bias favouring patients who were selected for NAC; however, the OS benefit was not evident in patients with persistent pT3‐T4N0M0 disease. This study underscores the importance of future research investigating methods to identify patients who will respond to NAC for bladder cancer. It also highlights the need to consider adjuvant therapy in patients who have persistent MIBC after NAC.

Editorial: The bladder cancer conundrum: how do we treat the right tumour with the right treatment, at the right time?

The bladder cancer conundrum is how to accurately determine the type of tumour, treatment and timing that is ideal for each patient? This is epitomised by the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for muscle‐invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). MIBC is a deadly disease; if untreated, the 2‐year mortality rate is 85% [1] and even if treated the overall survival (OS) rate at 5 years is 50%. In this context, NAC is appealing because it may improve outcomes. In 2003, a landmark study by Grossman et al. [2] examined NAC prior to radical cystectomy (RC) for MIBC. The median survival (44 vs 77 months, P = 0.06) and pT0 rates, which equate to the best survival rates (30% vs 15%, P < 0.001), were improved with NAC. A meta‐analysis of 11 randomised control trials in >3000 patients reported an OS benefit of 5% at 5 years with platinum‐based NAC [3]. Whilst NAC improves outcomes, especially for those patients who achieve pT0, it is also important to examine outcomes for patients with persistent MIBC and to determine if NAC is helpful in those patients.

In this issue of the BJUI, Lane et al. [4] attempt to answer this question by examining outcomes for patients with persistent MIBC after RC alone or NAC followed by RC. Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)‐Medicare data, the authors examined 1505 patients that underwent RC alone and 381 patients that received NAC and RC from 2004 to 2011. The authors report that after propensity weighted Kaplan–Meier analysis, the 5‐year OS rate was improved amongst patients that received NAC and RC as compared to patients that had RC alone if there was pT2–T4N0M0 disease on final pathology (43.5% vs 37.2%, P = 0.001). However, there was no difference in cancer‐specific survival (CSS) for NAC with RC compared to only RC (53.7% vs 58.4%, P = 0.76). After adjusting for confounders, the authors found similar results. The use of NAC and RC was found to have an OS benefit (hazard ratio [HR] 0.79, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.67–0.94; P = 0.006) for pT2–4N0M0 patients but not a CSS benefit (HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.72–1.08; P = 0.23).

Since previous studies have established the value of NAC in patients that are down‐staged to pT0 disease, the authors also focused their subset analysis on patients not down‐staged and instead had persistent MIBC. On subset analysis, NAC and RC patients with pT2N0M0 disease had an OS but no CSS benefit. For pT3–T4N0M0 patients, there was no OS or CSS benefit. This may suggest that a subset of non‐responders, such as those with pT2 disease, may experience some benefit from NAC despite persistent disease. Lastly, it is worth noting that whilst NAC improves outcomes, is better tolerated before surgery than adjuvant therapy, and is supported by high‐quality evidence, utilisation remains suboptimal. In this study [4], 381 of 1886 patients (or only 20%) had NAC and only 55% of these received cisplatin‐based therapy. Utilisation patterns vary and updated studies may show different results though. Overall, the authors should be congratulated for a study that is relevant, thoughtful and directed at an important clinical topic.

In this study [4], one issue that is raised is the challenges of accurate preoperative staging. The authors in this paper analysed patients according to pathological stage to limit confounding, as determining the exact stage of patients prior to NAC and RC cannot be done exactly. In this study, pT2 patients had on OS benefit after NAC but pT3–4 patients did not benefit. Clinical staging relies on transurethral resection, imaging and examination under anaesthesia to establish the diagnosis. Without final staging, it is difficult to precisely parse out which patients are clinical T2 vs T3 disease before RC. Predicting which patients are non‐responders is particularly important because these patients may be exposed unnecessarily to the risks of chemotherapy and may have delays in surgery that can negatively impact their outcomes. Therefore, even if the optimal treatment is known, identifying which patients will benefit can be challenging.

Fortunately, there is an exciting future for MIBC on the horizon. First, traditionally bladder cancer staging relies on determining the depth of invasion. In the future, more refined categorisation may help better characterise tumour subtypes. Through innovative multiplatform analyses, an improved understanding of distinct subtypes in bladder cancer has emerged [5]. Consequently, better subtype recognition may herald more targeted, and effective, therapy. Next, it is essential to determine the right type of treatment. Now, NAC is the standard of care for MIBC. However, there are several exciting trials examining other effective options to be used alternatively or synergistically. For example, the use of immunotherapy in the preoperative space is being studied and may shift how we manage MIBC. Lastly, the question of timing is key. Now, the order of surgery and systemic therapy may be a new frontier and perhaps the most significant question we are trying to solve. The possibility of understanding new subtypes of tumours and having new treatment options may require new timing for specific therapies in certain patients. It is conceivable that certain subtypes would be best managed with systemic therapy immediately whilst others with upfront surgery.

Certainly, more work needs to be done. So, what can we do now? We can promote the overall well‐being of our patients. Urologists can be conduits to help patients live healthy lifestyles and engage in behaviours that will promote psychological stability and physical strength. Encouraging daily activity, increasing fruit and vegetable consumption and, if needed, weight loss are options. Smoking cessation represents an imperative opportunity where urologists can make a positive impact [6]. Prehabilitation programmes focused on preparation for surgery can be done during NAC or while waiting for surgery and incorporate these elements. In this way, waiting time is leveraged to make small but cumulative improvements – ‘a little bit at a time’ is possible.

For now, we will continue to study the bladder cancer conundrum: subtypes of tumours, various treatments, and the best timing for therapy. Regardless of these results, it is likely patients with bladder cancer will still need some combination of surgery, systematic therapy and supportive care while they heal. In the interim, promoting well‐being is one way to help patients live healthier lives whilst making them more resilient to undergo whatever treatments may emerge next.

by Matthew Mossanen and Adam S. Kibel

References

- , . The prognosis with untreated bladder tumors. Cancer 1956; 9: 551– 8

- , , et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 859– 66

- Advanced Bladder Cancer Overview Collaboration. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for invasive bladder cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 2: CD005246.

- , , , , . Persistent muscle‐invasive bladder cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: an analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results‐Medicare data. BJU Int 2019; 123: 818– 25

- , , et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of muscle‐invasive bladder cancer. Cell 2018; 174: 1033

- , , , . Treating patients with bladder cancer: is there an ethical obligation to include smoking cessation counseling? J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 3189– 91

Residents’ podcast: Vaccines for preventing recurrent UTIs

Maria Uloko is a Urology Resident at the University of Minnesota Hospital. In this podcast she discusses the following BJUI Article of the Week:

Vaccines for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infections: a systematic review

Abstract

Objectives

To systematically review the evidence regarding the efficacy of vaccines or immunostimulants in reducing the recurrence rate of urinary tract infections (UTIs).

Materials and Methods

The Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE), PubMed, Cochrane Library, World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal, and conference abstracts were searched up to January 2018 for English‐titled citations. Randomised placebo‐controlled trials evaluating UTI recurrence rates in adult patients with recurrent UTIs treated with a vaccine were selected by two independent reviewers according to the Population, Interventions, Comparators, and Outcomes (PICO) criteria. Differences in recurrence rates in study populations for individual trials were calculated and pooled, and risk ratios (RRs) using random effects models were calculated. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool and heterogeneity was assessed using chi‐squared and I2 testing. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to evaluate the quality of evidence (QOE) and summarise findings.

Results

In all, 599 records were identified, of which 10 studies were included. A total of 1537 patients were recruited and analysed, on whom data were presented. Three candidate vaccines were studied: Uro‐Vaxom® (OM Pharma, Myerlin, Switzerland), Urovac® (Solco Basel Ltd, Basel, Switzerland), and ExPEC4V (GlycoVaxyn AG, Schlieren, Switzerland). At trial endpoint, the use of vaccines appeared to reduce UTI recurrence compared to placebo (RR 0.74, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.67–0.81; low QOE). Uro‐Vaxom showed the greatest reduction in UTI recurrence rate; the maximal effect was seen at 3 months compared with 6 months after initial treatment (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.57–0.78; and RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.69–0.88, respectively; low QOE). Urovac may also reduce risk of UTI recurrence (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.63–0.89; low QOE). ExPEC4V does not appear to reduce UTI recurrence compared to placebo at study endpoint (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.62–1.10; low QOE). Substantial heterogeneity was observed across the included studies (chi‐squared = 54.58; P < 0.001, I2 = 84%).

Conclusions

While there is evidence for the efficacy of vaccines in patients with recurrent UTIs, significant heterogeneity amongst these studies renders interpretation and recommendation for routine clinical use difficult at present. Further randomised trials using consistent definitions and endpoints are needed to study the long‐term efficacy and safety of vaccines for infection prevention in patients with recurrent UTIs.

Article of the week: The impact on oncological outcomes after RP for PCa of converting soft tissue margins at the apex and bladder neck from tumour‐positive to ‐negative

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community and the authors have also kindly produced a video describing their work. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

The impact on oncological outcomes after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer of converting soft tissue margins at the apex and bladder neck from tumour‐positive to ‐negative

Abstract

Objectives

To assess the impact of conversion from histologically positive to negative soft tissue margins at the apex and bladder neck on biochemical recurrence‐free survival (BCRFS) and distant metastasis‐free survival (DMFS) after radical prostatectomy (RP) for prostate cancer.

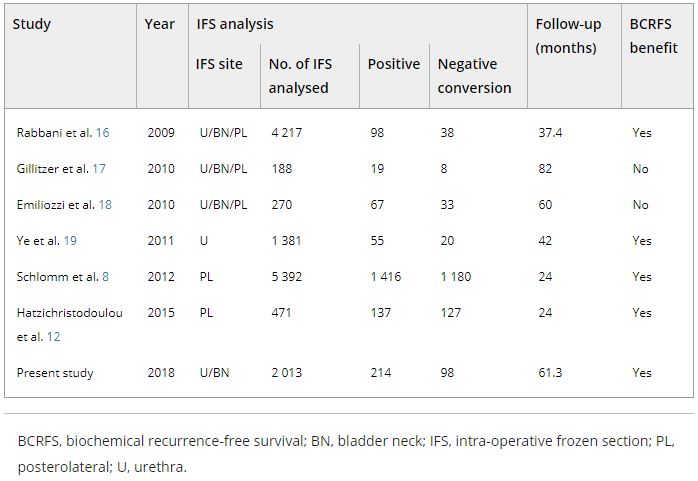

Materials and Methods

The records of 2 013 patients who underwent RP and intra‐operative frozen section (IFS) analysis between July 2007 and June 2016 were reviewed. IFS analysis of the urethra and bladder neck was performed, and if malignant or atypical cells remained, further resection with the aim of achieving histological negativity was carried out. Patients were divided into three groups according to the findings: those with a negative surgical margin (NSM), a positive surgical margin converted to negative (NCSM) and a persistent positive surgical margin (PSM).

Table 4. Impact of converting margins from tumour‐positive to ‐negative on biochemical recurrence

Results

Among the 2 013 patients, rates of NSMs, NCSMs and PSMs were 75.1%, 4.9%, and 20.0%, respectively. The 5‐year BCRFS rates of patients with NSMs, NCSMs and PSMs were 89.6%, 85.1% and 57.1%, respectively (P < 0.001). In both pathological (p)T2 and pT3 cancers, the 5‐year BCRFS rate for patients with NCSMs was similar to that for patients with NSMs, and higher than for patients with PSMs. The 7‐year DMFS rates of patients with NSMs, NCSMs and PSMs were 97.8%, 99.1% and 89.4%, respectively (P < 0.001). Among patients with pT3 cancers, the 7‐year DMFS rate was significantly higher in the NCSM group than in the PSM group (98.0% vs 86.7%; P = 0.023), but not among those with pT2 cancers (100% vs 96.9%; P = 0.616). The 5‐year BCRFS rate for the NCSM group was not significantly different from that of the NSM group among the patients with low‐ (96.3% vs 95.8%) and intermediate‐risk disease (91.1% vs 82.8%), but was lower than that of the NSM group among patients in the high‐risk group (73.2% vs 54.7%).

Conclusions

Conversion of the soft tissue margin at the prostate apex and bladder neck from histologically positive to negative improved the BCRFS and DMFS after RP for prostate cancer; however, the benefit of conversion was not apparent in patients in the high‐risk group.

Editorial: Conversion to negative surgical margin after intraoperative frozen section – (un)necessary effort and relevance in 2019?

The assessment and impact of positive surgical margins (PSMs) at the time of radical prostatectomy (RP) have been discussed for many decades. The determination and reporting should be performed in a standardised fashion according to the International Society of Urological Pathology [1]. The SM is considered positive if tumour cells touch the inked surface of the RP specimen. However, reasons for difficulty in truly differentiating between negative SMs (NSMs) and PSMs include iatrogenic disruption of the prostatic capsule, penetration of ink into small cracks on the outside, or cases in which prostate cancer cells are very close to, but not definitely touching, the inked margins.

A systematic review by Yossepowitch et al. [2] found a contemporary PSM rate of 15% (range 6.5–32%), which increases with extracapsular extension. In addition, the likelihood of PSM is strongly influenced by surgeon experience, independent of the surgical technique. Although PSM is considered an adverse pathological outcome and associated with an increased risk of biochemical recurrence (BCR), the impact on long‐term survival and actual prognostic value remains debatable. The association with other endpoints, such as prostate‐cancer specific mortality and overall survival, is controversial and may be primarily influenced by other risk factors, such as preoperative PSA level, Gleason score, and pathological T‐stage [2].

The role of intraoperative frozen section analysis in order to reduce the PSM rate continues to evolve. In a study by von Bodman et al. [3], 92.3% of patients with a PSM on frozen‐section analysis could ultimately be converted to a NSM. Similar findings were reported by Schlomm et al. [4] in 5392 patients using the intraoperative neurovascular structure‐adjacent frozen section examination (NeuroSAFE) technique, PSMs were detected in 25%, leading to re‐resection and conversion to definitive NSMs in 86% of these patients. In the setting of increasing experience with intraoperative frozen section analysis, a false‐positive SM status was found in only 48 patients (3.3%).

The study by Pak et al. [5], published in this issue of the BJUI, reported that specimens with initial PSMs were converted to NSMs upon permanent specimen evaluation (NCSM) in 4.9% of 2013 men undergoing RP. In this subgroup, the 5‐year BCR‐free survival (BCRFS) rates did not differ from those observed in National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) low‐ and intermediate‐risk patients with an initially NSM. However, the benefit of conversion from an initial PSM to final NSM was not apparent in high‐risk patients, as the authors found a significantly lower rate of BCRFS amongst this NCSM group. In multivariate analysis, NCSM status was independently associated (hazard ratio 0.624, P = 0.033) with BCR but not distant metastasis. These findings corroborate the findings of the Schlomm et al. [4] study, in which the BCRFS rates of propensity score‐based matched patients with conversion to NSMs did not differ significantly from patients with primarily NSMs.

What is the current role of intraoperative frozen section analysis during RP? How important is it to achieve NSMs in contemporary practice? In whom and how should the assessment be performed? Although it is clearly desirable to completely remove the entire tumour at the time of surgery, and NSMs are a surrogate marker of adequate local excision, the devil is in the details. First, in this study [5], the authors only assessed SMs at the bladder neck and apex. Although the apex is one of the most frequent locations for PSMs, other and/or multiple sites of PSMs are possible and could have been missed. Alternatively, the NeuroSAFE method is able to assess the entire laterorectal circumference albeit with the trade‐off of more extensive pathological involvement and assessment. Second, intraoperative frozen section analysis, and manoeuvers for NCSM, may ultimately be necessary and beneficial in only a small number of patients currently undergoing RP. An increasing proportion of men harbour more aggressive, higher‐risk disease in whom PSMs may have no impact on oncological outcomes or treatment decisions. In these men, long‐term cancer outcomes are probably more related to risks of unsuspected metastatic disease rather than residual, microscopic cancer within the prostatic fossa. As suggested in this study [5], an initial PSM in high‐risk men, independent of ultimate NCSM, may be a surrogate for non‐localised disease and poorer outcomes; PSMs were found in 53% of men with pT3b. In low‐risk men, the issues are whether active surveillance is a more appropriate initial management strategy and that routine intraoperative frozen section analysis may not be worthwhile with a PSM rate of only 10%. How does this alter the decision for adjuvant therapy? Adjuvant radiotherapy is probably under‐utilised in men with PSMs after RP (~11%), and NCSM may spare men from unnecessary treatment, particularly with lower‐risk disease [6]. However, men with PSMs and additional adverse pathological features, such as extraprostatic extension or seminal vesicle invasion, should probably receive adjuvant therapy, primarily driven by T stage.

The incremental value and potential clinical benefit of intraoperative frozen section analysis to achieve NSMs remain to be determined. Although one would suspect that PSM leading to excision of additional tissue could lead to worse functional outcomes, the study from Mirmilstein et al. [7] is reassuring. Despite higher Gleason score and pT stage in those undergoing the NeuroSAFE approach, the PSM rate was lower in this group (9.2%) compared with those undergoing standard intraoperative nerve‐sparing while leading to greater bilateral nerve preservation, higher potency rates at 12 months, and pad‐free continence.

In the future, other methods may guide surgical decision‐making and may eventually alter PSM rate including preoperative MRI of the prostate to evaluate extracapsular extension, genomic risk scores, or real‐time, near‐infrared fluorescent surgical guidance with prostate‐specific membrane antigen ligands [8]. However, one should not forget that outcomes are not solely based on the SM status. Various pathological and clinical factors and patients’ comorbidities and preference should be taken into consideration in the surgical management and that evaluation of validated oncological and functional outcomes is critical.

by Annika Herlemann and Maxwell Meng

References

- , , et al. International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Handling and Staging of Radical Prostatectomy Specimens. Working group 5: surgical margins. Mod Pathol 2011; 24: 48– 57

- , , et al. Positive surgical margins after radical prostatectomy: a systematic review and contemporary update. Eur Urol 2014; 65: 303– 13

- , , et al. Intraoperative frozen section of the prostate decreases positive margin rate while ensuring nerve sparing procedure during radical prostatectomy. J Urol 2013; 190: 515– 20

- , , et al. Neurovascular structure‐adjacent frozen‐section examination (NeuroSAFE) increases nerve‐sparing frequency and reduces positive surgical margins in open and robot‐assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: experience after 11,069 consecutive patients. Eur Urol 2012; 62: 333– 40

- , , , , , . The impact on oncological outcomes after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer of converting soft tissue margins at the apex and bladder neck from tumour‐positive to ‐negative. BJU Int 2019; 123: 811– 7

- , , et al. National trends in the management of patients with positive surgical margins at the time of radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36 (Suppl.): 111

- , , et al. The neurovascular structure‐adjacent frozen‐section examination (NeuroSAFE) approach to nerve sparing in robot‐assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy in a British setting – a prospective observational comparative study. BJU Int 2018;121: 854– 62

- , , et al. Real‐time, near‐infrared fluorescence imaging with an optimized dye/light source/camera combination for surgical guidance of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 771– 80