Editorial: Early stent removal after pyeloplasty

In the current issue of BJUI Danuser et al. [1] present their prospective randomised single-centre study evaluating the effectiveness of 1-week vs the more traditional 4-week ureteric stent placement, after either a laparoscopic (LPP) or robot-assisted laparoscopic pyeloplasty procedure (RALPP) for PUJO.

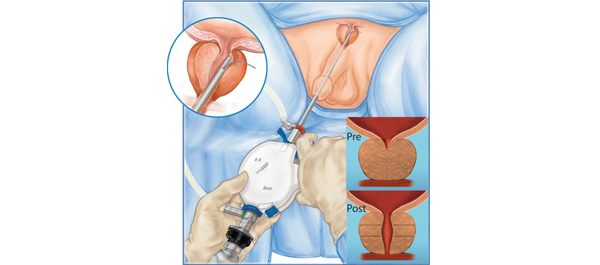

In recent years LPP and RALPP have become the standard treatments for PUJO. In the adult population most patients undergoing this procedure require a period of ureteric stenting with a JJ stent, while the newly formed anastomosis heals. Many published pyeloplasty series report a stenting period of between 3 and 6 weeks [2-4]. The present study questions the need for such an extended period of stenting. With current minimal access techniques, either LPP or RALPP, it is possible to create a direct anastomosis between the ureter and renal pelvis similar to, and some would argue even more accurately than, that achievable via open surgery. The authors make the case that as historically most open pyeloplasty procedures were successfully stented for a period of 1 week, it seems only right to question why many of us continue to leave our ureteric stents in for longer periods after LPP and RALPP.

The negative impact of ureteric stent placement on patient health-related quality of life has been well documented in the literature. In 2003, Joshi et al. [5] published their study investigating the prevalence of symptoms associated with ureteric stents. They found that 78% of patients reported bothersome urinary symptoms that included storage symptoms, incontinence and haematuria, and >80% of patients had stent-related pain affecting daily activities. Furthermore, 58% reported reduced capacity to work and 32% reported sexual dysfunction. With this in mind, it is clear why we should try to reduce the period of ureteric stenting wherever possible, as long as it does not compromise patient outcome.

Danuser et al. [1] studied 100 consecutive patients with PUJO treated by an Anderson-Hynes pyeloplasty performed laparoscopically or robotically. Patients were randomly assigned to have a 6-F JJ catheter for either 1 week, or for 4 weeks. Their primary outcome, success rate (defined as no obstruction on the IVU or renogram), was 100% in the 1-week group and 98% in the 4-week group (P = 0.006), showing that 1 week is equally effective. For secondary outcomes measures they found no difference in residual symptoms, rate of complications, need for synchronous robot-assisted pyelolithotomy, improvement in split renal function and duration of surgery between the two groups. They therefore conclude that stenting of the PUJO anastomosis for 1 week after LPP or RALPP is as effective as stenting for 4 weeks.

We are all responsible for constantly evaluating and challenging our medical and surgical practice to ensure that we are providing the best care possible for our patients. In surgery, in the absence of high-level evidence, many of the decisions and actions we take are those inherited from our teachers and mentors, as practices that are thought to be safe and effective. Postoperative patient management is one area where clinicians vary greatly in their practice and we all strive to ensure a safe and comfortable recovery for patients, while not compromising on surgical outcome.

In the postoperative management of pyeloplasty patients many of us continue to leave ureteric stents in for up to 4–6 weeks, as this is ‘safe’ practice. It has been my observation that despite careful counselling of what patients should expect postoperatively when they have a ureteric stent in situ, many complain of stent symptoms and often seek medical advice. This prospective randomised single-centre study by Danuser et al. [1] provides us with good evidence to support the role for a shorter duration of stenting, particularly in this group of patients where a good anastomosis can be created, without compromising patient outcome.

Jane Letitia Boddy

Department of Urology, New Cross Hospitals NHS Trust, Wolverhampton, UK

References

-

Danuser H, Germann C, Pelzer N, Rühle A, Stucki P, Mattei A. One-week versus four-week stent placement following laparoscopic and robotic assisted pyeloplasty – Results of a prospective randomized single-centre study. BJU Int 2014; 113: 931–935

-

Chow K, Adeyoju AA, Section of Endourology of The British Association of Urological Surgeons. National practice and outcomes of laparoscopic pyeloplasty in the United Kingdom. J Endourol 2011; 25: 657–662

-

Singh O, Gupta SS, Hastir A, Arvind NK. Laparoscopic dismembered pyeloplasty for ureteropelvic junction obstruction: experience with 142 cases in a high-volume centre. J Endourol 2010; 24: 1431–1434

-

Mufarrij PW, Woods M, Shah OD et al. Robotic dismembered pyeloplasty: a 6 year, multi-institutional experience. J Urol 2008; 180: 1391–1396

-

Joshi HB, Stainthorpe A, MacDonagh RP, Keeley FX Jr, Timoney AG, Barry MJ. Indwelling ureteral stents: evaluation of symptoms, quality of life and utility. J Urol 2003; 169: 1065–1069