Posts

Article of the week: Prostate cancer in kidney transplant recipients – a nationwide register study

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to this post, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community and a video produced by the authors. Please use the comment buttons below to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

Prostate cancer in kidney transplant recipients – a nationwide register study

Ola Bratt*†, Linda Drevin‡, Karl-Göran Prütz§, Stefan Carlsson¶, Lars Wennberg** and Pär Stattin††

*Department of Urology, Institute of Clinical Science, Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg University, †Department of Urology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, ‡Regional Cancer Centre, Uppsala-Orebro, Uppsala, §Swedish Renal Registry, Ryhov Hospital, Jönköping, ¶Section of Urology, Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institute, **Department of Transplantation Surgery, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, and ††Department of Surgical Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

Abstract

Objective

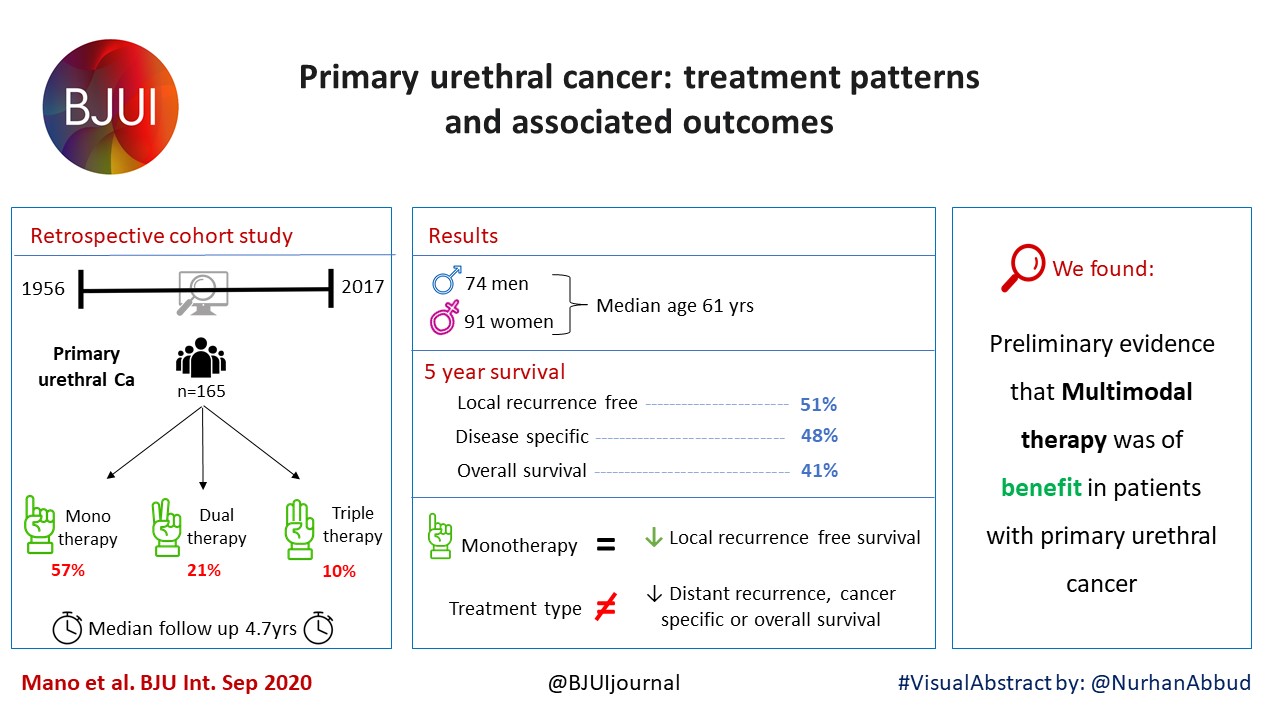

To investigate whether post‐transplantation immunosuppression negatively affects prostate cancer outcomes in male kidney transplant recipients.

Patients and Methods

We used the Swedish Renal Register and the National Prostate Cancer Register to identify all kidney transplantation recipients diagnosed with prostate cancer in Sweden 1998–2016. After linking these registers with Prostate Cancer Database Sweden (PCBaSe), a case‐control study was designed to compare time period and risk category‐specific probabilities of a prostate cancer diagnosis amongst kidney transplantation recipients versus the male general population. The registers did not include information about the specific immunosuppression agent used in all transplantation recipients. Data from PCBaSe were used to compare prostate cancer characteristics at diagnosis and survival for patients with prostate cancer with versus without a kidney transplant. Propensity score matching, Cox regression analysis and Fisher’s exact test were used and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated.

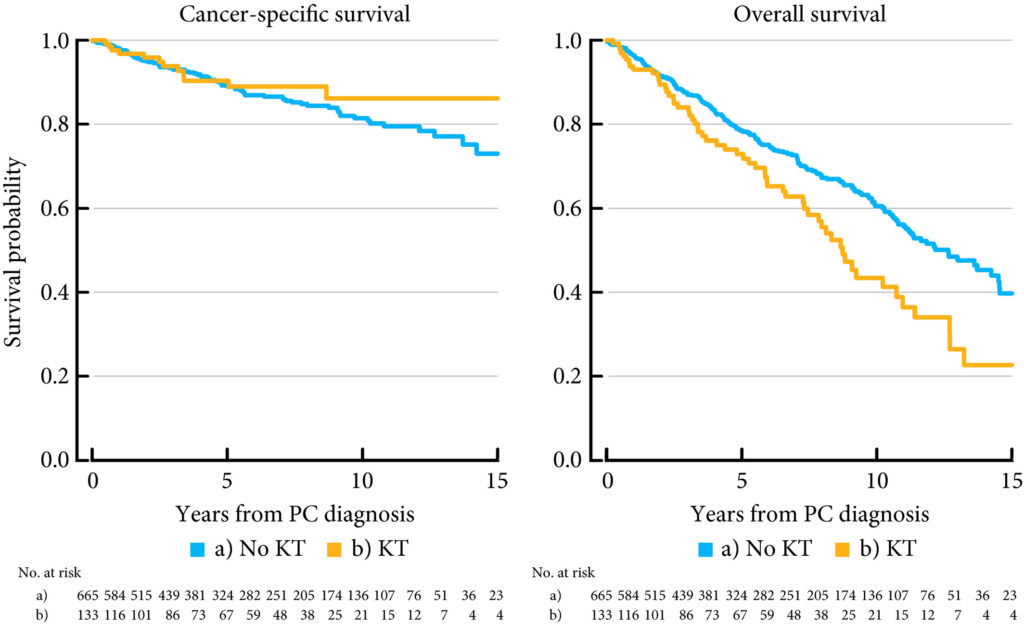

Results

Almost half of the 133 kidney transplantation recipients were transplanted before the mid‐1990s, when PSA testing became common in cancer centers. The transplant recipients were not more likely than age‐matched control men to be diagnosed with any (odds ratio [OR] 0.84, 95% CI 0.70–0.99) or high‐risk or metastatic prostate cancer (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.62–1.13). None of the ORs for the different categories of prostate cancer increased with time since transplantation. Cancer characteristics at the time of diagnosis and cancer‐specific survival were similar amongst transplant recipients and the control group of 665 men diagnosed with prostate cancer without a kidney transplant.

Conclusions

This Swedish nationwide, register‐based study gave no indication that immunosuppression after kidney transplantation increases the risk of prostate cancer or adversely affects prostate cancer outcomes. The study suggests that men with untreated low‐grade prostate cancer can be accepted for transplantation.

Video: Prostate cancer in kidney transplant recipients – a nationwide register study

:

Prostate cancer in kidney transplant recipients – a nationwide register study

Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether post‐transplantation immunosuppression negatively affects prostate cancer outcomes in male kidney transplant recipients.

Patients and Methods

We used the Swedish Renal Register and the National Prostate Cancer Register to identify all kidney transplantation recipients diagnosed with prostate cancer in Sweden 1998–2016. After linking these registers with Prostate Cancer Database Sweden (PCBaSe), a case‐control study was designed to compare time period and risk category‐specific probabilities of a prostate cancer diagnosis amongst kidney transplantation recipients versus the male general population. The registers did not include information about the specific immunosuppression agent used in all transplantation recipients. Data from PCBaSe were used to compare prostate cancer characteristics at diagnosis and survival for patients with prostate cancer with versus without a kidney transplant. Propensity score matching, Cox regression analysis and Fisher’s exact test were used and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated.

Results

Almost half of the 133 kidney transplantation recipients were transplanted before the mid‐1990s, when PSA testing became common. The transplant recipients were not more likely than age‐matched control men to be diagnosed with any (odds ratio [OR] 0.84, 95% CI 0.70–0.99) or high‐risk or metastatic prostate cancer (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.62–1.13). None of the ORs for the different categories of prostate cancer increased with time since transplantation. Cancer characteristics at the time of diagnosis and cancer‐specific survival were similar amongst transplant recipients and the control group of 665 men diagnosed with prostate cancer without a kidney transplant.

Conclusions

This Swedish nationwide, register‐based study gave no indication that immunosuppression after kidney transplantation increases the risk of prostate cancer or adversely affects prostate cancer outcomes. The study suggests that men with untreated low‐grade prostate cancer can be accepted for transplantation.

Article of the Month: Perineal repair of PFUI – In pursuit of a successful outcome

Every Month the Editor-in-Chief selects the Article of the Month from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Perineal repair of pelvic fracture urethral injury – In pursuit of a successful outcome

OBJECTIVE

To determine perioperative factors that may optimize the outcome after delayed perineal repair of a pelvic fracture urethral injury (PFUI).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

In all, 86 consecutive patients who underwent perineal repair of a PFUI between 2004 and 2011 were prospectively enrolled in this study. The mean (range) patient age was 23 (5–50) years. The mean (range) follow-up was 5.5 (2–8) years. We examined seven perioperative variables that might influence the outcome including: prior failed treatment, condition of the bulbar urethra, displacement of the prostate, excision of scarred tissues, fixation of the mucosae of the two urethral ends, and the number and size of sutures used for urethral anastomosis. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to identify factors that influence postoperative outcome.

RESULTS

Of the patients, 76 (88%) had successful outcomes and 10 (12%) were considered treatment failures. On univariate analysis, four variables were significant factors influencing the outcome: excision of scarred tissues, prostatic displacement, condition of the bulbar urethra and fixation of the mucosae. On multivariate analysis only two remained strong and independent factors namely complete excision of scarred tissues and prostatic displacement in a lateral direction.

CONCLUSIONS

Meticulous and complete excision of scar tissue is critically important to optimise the outcome after perineal urethroplasty. This is particularly emphasised in cases associated with lateral prostatic displacement. Six sutures of 3/0 or 4/0 polyglactin 910 are usually sufficient to create a sound urethral anastomosis. Prior treatment and scarring of the anterior urethra do not affect the outcome.

Editorial: Specialty within a specialty – posterior urethroplasty

Posterior urethral distractions occur in up to 25% of cases of blunt force pelvic fractures. Proper repair of these pelvic fracture urethral injuries (PFUI) is an art that requires exquisite attention to technique and tissue handling. Koraitim and Kamel [1] recently reported their single-surgeon series of PFUI repairs on 86 patients, with the specific aim of characterizing risk factors for treatment failure. Success was defined subjectively as absence of urinary symptoms and normal postoperative urethrography. Requirement for repeat procedures constituted failure. At a mean 5.5 years of direct follow-up, 88% of patients were considered to have had successful treatment. Multivariate logistic regression showed that incomplete scar excision and lateral prostatic displacement (as opposed to superior or no displacement) were predictive of treatment failure (odds ratios 122 and 34, respectively). All other factors analysed, including previous treatment, relative bulbar urethral scarring, mucosal fixation, suture size and number of sutures, were not significant predictors of urethral outcomes.

Large patient series of posterior urethroplasty report treatment success rates of 86–97%, although follow-up has been short in general [2-4]. The present report by Koraitim and Kamel compares favourably with these series, despite longer patient follow-up. This suggests that late failures after posterior urethral repair are rare. The authors should be commended for their desire to ascertain risk factors for failure after repair of these urethral injuries; however, several factors that probably affect outcomes were not evaluated and may at least partially explain some of their treatment failures.

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is known to occur in ~5% of men after pelvic fracture, and to increase to a mean of 42% in those with a concomitant urethral injury [5]. A portion of these men with ED will have arterial insufficiency and will be at increased risk of bulbar necrosis and ischaemic stenosis. Before urethral reconstruction, men with ED should be evaluated with penile duplex ultrasonography and, if arteriogenic ED is suggested, pelvic angiogram. In those with bilateral complete obstruction of the deep internal pudendal or common penile arteries, revascularization should be offered before urethral reconstruction. In this patient population, penile revascularization has been shown to reverse arterial insufficiency, leading to both improved erections and enhanced tissue perfusion for optimum outcomes after posterior urethral reconstruction [6].

A progressive perineal approach has been popularized by Webster and Ramon [4] and generally accepted by those regularly performing posterior urethral reconstruction. While the present authors report extensively on relative excision of fibrosis and number, type and location of suture utilization, they do not provide insight into the number of ancillary measures necessary for a tension-free repair. While some argue that the importance of crural separation and infrapubectomy are overstated [3], these techniques are essential in some patients in order to achieve a tension-free anastomosis. Given that fibrosis was incompletely excised in 15% of patients in this cohort, some of these same patients may also have had some degree of tension of the urethral anastomosis. Alternatively, these adjunctive procedures may be independent predictors of treatment success or failure and their role in this series would be interesting to note.

It is our experience, and surely that of others, that direct long-term follow-up after urethroplasty at a tertiary referral centre is often difficult or non-existent. These authors should be applauded for their ability to follow their patients for a mean 5.5 years in this series. They have provided much needed extended outcome data after posterior urethral reconstruction. The challenge going forward will be for high-volume centres of reconstruction to design studies prospectively that answer specific questions using standardized instruments and objective results.

Complete remission of rapidly-progressing, unilateral, primary adrenal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with surgery and rituximab-chop chemotherapy

We report a patient with a massive adrenal tumor treated with early surgical intervention due to concern for that an adrenocortical carcinoma was present.

Authors: Michael J. Lyons1, Anthony J. Kubat1, Stephen N. Huang1, Richard J. Kahnoski1,2,

Brian R. Lane1,2,3

Corresponding Author: Brian R. Lane, M.D., Ph.D. Urology Division, Spectrum Health Medical Group, 4069 Lake Drive, Suite 313, Grand Rapids, MI 49546. Tel: 616-267-7333; E-mail: [email protected]

Date added to bjui.org: 06/02/2012

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2011-119-web