Article of the Week: Prevalence of the HOXB13 G84E mutation in Danish men undergoing radical prostatectomy and its correlations with prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness

Every Week the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an accompanying editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community. This blog is intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Prevalence of the HOXB13 G84E mutation in Danish men undergoing radical prostatectomy and its correlations with prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness

Objectives

To determine the prevalence of the HOXB13 G84E mutation (rs138213197) in Danish men with or without prostate cancer (PCa) and to investigate possible correlations between HOXB13 mutation status and clinicopathological characteristics associated with tumour aggressiveness.

Materials and Methods

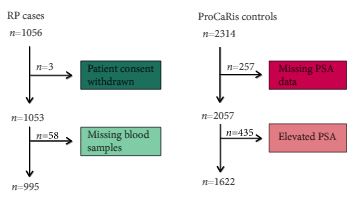

We conducted a case–control study including 995 men with PCa (cases) who underwent radical prostatectomy (RP) between 1997 and 2011 at the Department of Urology, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark. As controls, we used 1622 healthy men with a normal prostate specific antigen (PSA) level.

Results

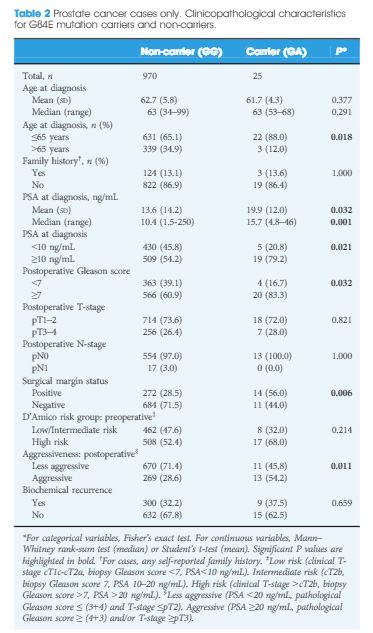

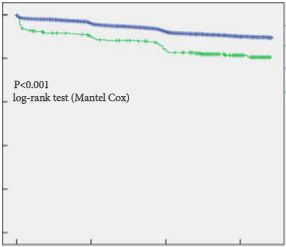

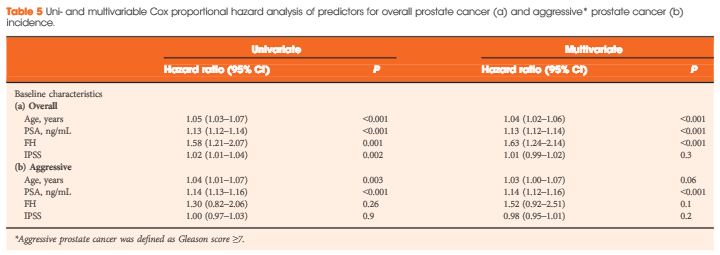

The HOXB13 G84E mutation was identified in 0.49% of controls and in 2.51% of PCa cases. The mutation was associated with a 5.12-fold increased relative risk (RR) of PCa (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.26–13.38; P = 13 × 10−6). Furthermore, carriers of the risk allele were significantly more likely to have a higher PSA level at diagnosis (mean PSA 19.9 vs 13.6 ng/mL; P = 0.032), a pathological Gleason score ≥7 (83.3 vs 60.9%; P = 0.032), and positive surgical margins (56.0 vs 28.5%; P = 0.006) than non-carriers. Risk allele carriers were also more likely to have aggressive disease (54.2 vs 28.6%; P = 0.011), as defined by a preoperative PSA ≥20 ng/mL, pathological Gleason score ≥ (4+3) and/or presence of regional/distant disease. At a mean follow-up of 7 months, we found no significant association between HOXB13mutation status and biochemical recurrence in this cohort of men who underwent RP.

Conclusions

This is the first study to investigate the HOXB13 G84E mutation in Danish men. The mutation was detected in 0.49% of controls and in 2.51% of cases, and was associated with 5.12-fold increased RR of being diagnosed with PCa. In our RP cohort, HOXB13 mutation carriers were more likely to develop aggressive PCa. Further studies are needed to assess the potential of HOXB13 for future targeted screening approaches.