STAMPEDE at the Dumball rally

I’m sure I’m not the only one to board a long haul flight with the aim of catching up on a little CPD reading, only to be led astray by a series of films that later I’ll never admit to watching. Still they can be educational, as having stopped studying History at the age of 12 I’m ashamed to admit that without this educational medium I would never have been aware that the 16th President of the United States spent his formative years hunting Vampires. So in January 2016 I boarded a 10-hour flight from London to Chennai equipped with the latest publication from the STAMPEDE Study, a Workshop Manual for the Hindustan Ambassador, and a sense of inevitability that I’d be watching Matt Damon land on Mars before we’d finished crossing Kent. Taking a car manual for in-flight entertainment was not a cunning plan to encourage my neighbouring passengers to change seats before I engaged them in conversation. I have an unread copy of Donald Trump’s 2009 tome “Think Like a Champion” that fulfils that role perfectly. The manual was my homework, as I was en route to join the Dumball Rally.

I’m sure I’m not the only one to board a long haul flight with the aim of catching up on a little CPD reading, only to be led astray by a series of films that later I’ll never admit to watching. Still they can be educational, as having stopped studying History at the age of 12 I’m ashamed to admit that without this educational medium I would never have been aware that the 16th President of the United States spent his formative years hunting Vampires. So in January 2016 I boarded a 10-hour flight from London to Chennai equipped with the latest publication from the STAMPEDE Study, a Workshop Manual for the Hindustan Ambassador, and a sense of inevitability that I’d be watching Matt Damon land on Mars before we’d finished crossing Kent. Taking a car manual for in-flight entertainment was not a cunning plan to encourage my neighbouring passengers to change seats before I engaged them in conversation. I have an unread copy of Donald Trump’s 2009 tome “Think Like a Champion” that fulfils that role perfectly. The manual was my homework, as I was en route to join the Dumball Rally.

The Dumball Rally is a fancy-dress charity banger rally – that raises money for the Teenage Cancer Trust. Since its inception in 2006 (Amsterdam to Athens) it has raised over £650,000. This year the route was Chennai to Goa, via Kanyakumari (the Southern Tip of India), the Western Ghats, Cochin, and for our team a stapes-shuddering Rock Bar in Mysore. 37 Hindustan Ambassadors awaited us on the start-line, their fully enclosed monocoque chassis based on the Morris Oxford Series III that last rolled off the production line in Cowley in 1959 – just in case you’re thinking I didn’t read the manual.

As a Clinical Oncologist I’m admit to being in one of the more geek-orientated specialities. Who needs a PDE5-inhibitor when a graph depicting a Bragg Peak excites you? So as I read about the history of Hindustan Motors, and the inner workings of my Ambassador, I was struck by the commonality of their significant anniversaries with those of my chosen profession. Hindustan Motors was founded in 1942, the year after Charles Huggins published his seminal paper on Prostate Cancer. The Morris Oxford Series III began production in 1956, the same year that Hertz and Li first described the successful use of cytotoxic chemotherapy (methotrexate) to treat a solid tumour (Choriocarcinoma). The production of the Hindustan Ambassador began in 1958, the year Rosalind Franklin died. The final version of the Ambassador (the Avigo) began production in 2004, the same year Tak327 was published demonstrating a survival advantage for Docetaxel and prednisone in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Who said altitude and wine don’t mix well?

The rally began on 10th January 2016. Our team, dressed as Dick Dastardly and Muttley (wise outfit choices in greater than 30 degrees centigrade heat), were pitted against a range of other themed cars from a fire-engine (with wired-in power washer), a yellow-submarine (broadcasting “Beatles” songs), to the Jungle Book (which continuously grew with foliage collected from the roadside). The Rally results are summarised below, and compared with the results from the STAMPEDE Study (finally read on the return flight).

STAMPEDE is a study assessing the impact of intensifying initial treatment for locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer. Its novel Multi-Arm Multi-Stage (MAMS) design may prove as important to future cancer care as the results generated by the study itself. Basically MAMs permits multiple different primary questions to be addressed simultaneously and sequentially over a far shorter time period, and with fewer subjects, than would be required to address the questions separately.

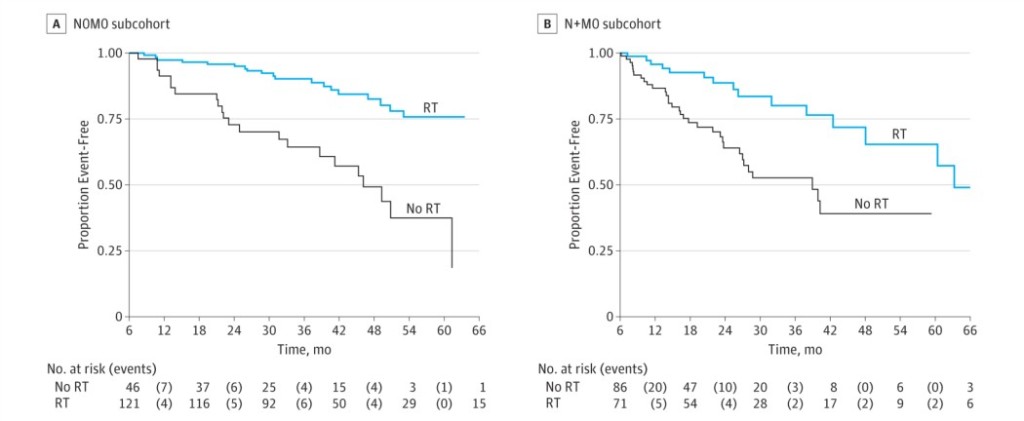

Median Overall Survival for the Standard of Care (SOC) arm of STAMPEDE was 71 months, which increased to 81 months with the addition of 6 cycles of Docetaxel Chemotherapy. There was no additional benefit with the use of Zoledronic acid (with or without Docetaxel). Looking at the subset with metastatic disease, Median Overall Survival increased from 45 months to 60 months with the addition of Docetaxel, demonstrating that this should now be standard of care in suitable patients with metastatic disease. Regarding the Median Overall Survival for the Dumball Rally, there were insufficient events (only 1 car had to be abandoned), and follow-up is too short (8 days) to report meaningful data.

Median Failure Free Survival (FFS) for the SOC arm of STAMPEDE was 20 months, which increased to 37 months with Docetaxel. The hazard ratios were similar for both metastatic and non-metastatic subsets. Again there was no additional benefit with the addition of Zolendronic acid. The median FFS for the Hindustan Ambassador was about 6 hours. The passenger seat and seat-belt broke in our car whilst exiting the car-park having just collected it; most cars over-heated daily (interestingly the electrics are located directly beneath the radiator overflow); one engine seized completely; and an axel broke on Dumball 1, the organiser’s car.

Grade 3 + adverse events reported within the first 6 months of the STAMPEDE Study increased from 17% in the SOC arm to 36% with the addition of Docetaxel. Despite this the chemotherapy was well tolerated, with most patients completing all 6 planned cycles with minimal changes in dose or scheduling. Regarding the Rally, ironically it coincided with India’s National Road Safety Week. Their slogan “Hurry leads to worry; Accident brings tears; Safety brings cheers” repeated Orwellian-style in my subconscious as we negotiated the Indian traffic. In India they drive on the left……and sometimes the right, the middle of the road, the pavement –in fact wherever they want! A gentle toot of the horn lets other road users know where they are, and it appears to be the driver’s responsibility to avoid anything in front of them – no matter how late it pulls out. But it works – and everything keeps moving with good humour and smiles. It wasn’t unusual to be horrendously cut-up, only for the “offending driver” to then stop, get out the car and come over for a friendly chat and a photo opportunity. As a result, there were minimal adverse events – other than putting on a few additional Kg in weight eating curry 3 times a day.

Work on next year’s Dumball Rally has already started – rumours are that it may involve Nepal. If anyone is interested in taking part, please look at their website: www.dumball.org

Simon Hughes is a Consultant Clinical Oncologist at Guy’s and St Thomas’, London