Editorial: Penile vibratory stimulation (PVS) a novel approach for penile rehabilitation post nerve sparing radical prostatectomy

The reported incidence of erectile dysfunction (ED) after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy (NS-RP) varies in the literature from 30 to 80% [1]. This can be explained by the state of neuropraxia which affects the cavernosal nerves, even if the nerves are anatomically intact. During this period there is a lack of nocturnal tumescence which leads to tissue hypoxia and ischaemic damage to the cavernosal smooth muscles leading to smooth muscle necrosis and fibrosis, which in turn causes veno-occlusive dysfunction (VOD). A study by Mulhall et al. [2] showed that, at 12 months after NS-RP, 50% of patients will have VOD and ED. The role of penile rehabilitation, therefore, is to maintain adequate tissue oxygenation until the cavernosal nerves recover with the return of the spontaneous nocturnal tumescence; thus, penile rehabilitation should not be confused with ED treatment. If you see yourself as religious, addiction may make you feel guilty or get you to feel isolated among your friends at your religious organization. A spiritual Christian rehab center in Orlando may be the right choice for you. Not only do you get to meet like-minded people to share your experiences in your journey to sobriety, but the process may also help you to rediscover your faith in God. Legacy Healing Center Tampa offer programs that make spiritual guidance an important part of every type of addiction treatment. Orange County law enforcement has taken steps to make sure the drugs are not as easily available as they once were. This has helped manage Orlando’s drug problem and kept it from turning worse. As important as prevention is to saving lives, however, to the hundreds who are already addicted, rehab is what helps. If you are religious or spiritual, faith-based drug rehab can be the answer to the challenges that you face. It’s important to remember that faith-based rehab only works well for those who are deeply spiritual or religious. Trying faith-based rehab when you are ambivalent about religion can work against you. You may find that you aren’t able to accept what you’re asked to practice, and you may find yourself rebelling. It’s important to choose a treatment approach that you can go along with in good conscience.

Several lines of treatment, including phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, intracavernous injection of alprostadil and vacuum pump therapy, have been used in penile rehabilitation but an agreed rehabilitation programme in terms of agents used, timing and duration of therapy does not yet exist [1].

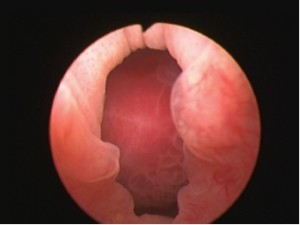

The present study by Fode et al. [3] reports a novel approach to penile rehabilitation using penile vibratory stimulation (PVS). The study looked into the effect of PVS on postoperative erection and continence. The Ferticare® vibrator (Fig. 1) was used at an amplitude of 2 mm and a vibration frequency of 100 Hz and applied to the frenulum once daily, with a sequence consisting of 10 s of stimulation followed by a 10-s rest and repeated 10 times.

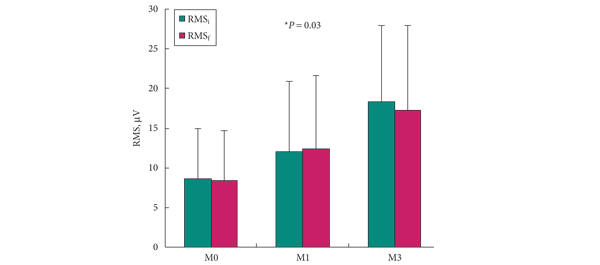

The results showed a trend towards better erection in the PVS group (n = 30) compared with the control group (n = 38) as evidenced by the higher International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) score, but the difference was not significant (P = 0.09). After 1 year, 16 patients (53%) in the PVS group had an IIEF score ≥18 compared with 12 (32%) patients in the control group (P = 0.07). The results did not show any effect of treatment on continence; at 12 months, 90% of the PVS group achieved continence compared with 94.7% of the control group (P = 0.46), although the PVS group had a significantly higher preoperative LUTS score which may explain the results.

The theory postulated is that application of PVS activates the parasympathetic erectile spinal centre (S2–S4), which in turn leads to activation of the cavernosal nerves, enhancing the healing process, and recovery from neuropraxia and restoration of spontaneous erections. Also this would lead to stimulation of the somatic S2–S4 spinal centre, which controls the pelvic floor muscles via the pudendal nerve, leading to the recovery of continence. Although this has been shown in patients with spinal cord injury as the authors mentioned; this may not be the case in post NS-RP with the nerves in a state of neurapraxia, whereas in patients with spinal cord injury the nerves are intact. It would have been of great value to conduct neurophysiological tests on these patients to demonstrate that, despite the cavernosal nerves being in a state of neurapraxia, nerve activity in response to PVS was actually present.

The rehabilitation protocol used in the present study started early but only continued for 6 weeks postoperatively. Studies have shown that the potential recovery time of erectile function after NS-RP is 6–36 months, with the majority recovering within 12–24 months [1,4]. The results might have shown statistical significance in favour of PVS, had treatment continued for a longer period. Starting PVS treatment in the early postoperative period may not be suitable in all patients; in this study six out of 36 patients (16.6%) were non-compliant with the protocol; four had prolonged catheterization and two experienced pain. Furthermore, neurophysiological testing is required to show that in the early postoperative period the cavernosal nerves are actually intact and therefore respond to PVS.

Although the results of the present study did not reach significance, they are encouraging, as there was a trend in favour of treatment with regard to erectile function. Further studies involving larger numbers of patients are warranted to investigate this new line of rehabilitation.

Amr Abdel Raheem*† and David Ralph†

*Andrology Department, Cairo University Hospital, Cairo, Egypt, and †St. Peter’s Andrology Centre, Institute of Urology, London, UK

References

- Mulhall JP, Bivalacqua TJ, Becher EF. Standard operating procedure for the preservation of erectile function outcomes after radical prostatectomy. J Sex Med 2013; 10: 195–203

- Mulhall JP, Slovick R, Hotaling J et al. Erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy: hemodynamic profiles and their correlation with the recovery of erectile function. J Urol 2002; 167: 1371–5

- Fode M, Borre M, Ohl D, Lichtbach J, Sønksen J. Penile vibratory stimulation in the recovery of urinary continence and erectile function after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: a randomized, controlled trial. BJU Int 2014; 114: 111–7

- Rabbani F, Schiff J, Piecuch M et al. Time course of recovery of erectile function after radical retropubic prostatectomy: does anyone recover after 2 years? J Sex Med 2010; 7: 3984–90