BAUS 2018 Highlights Day Three

BAUS Day 3—Going home images and snippets…

On the final night of BAUS, I had the honor of giving a dinner talk to the IBUS group—International British Urology Society. With BAUS contracting from 4 to 3 days, some of the previous joint sessions fell by the wayside, but IBUS president Subu Subramonian put together a nice evening program for the group.

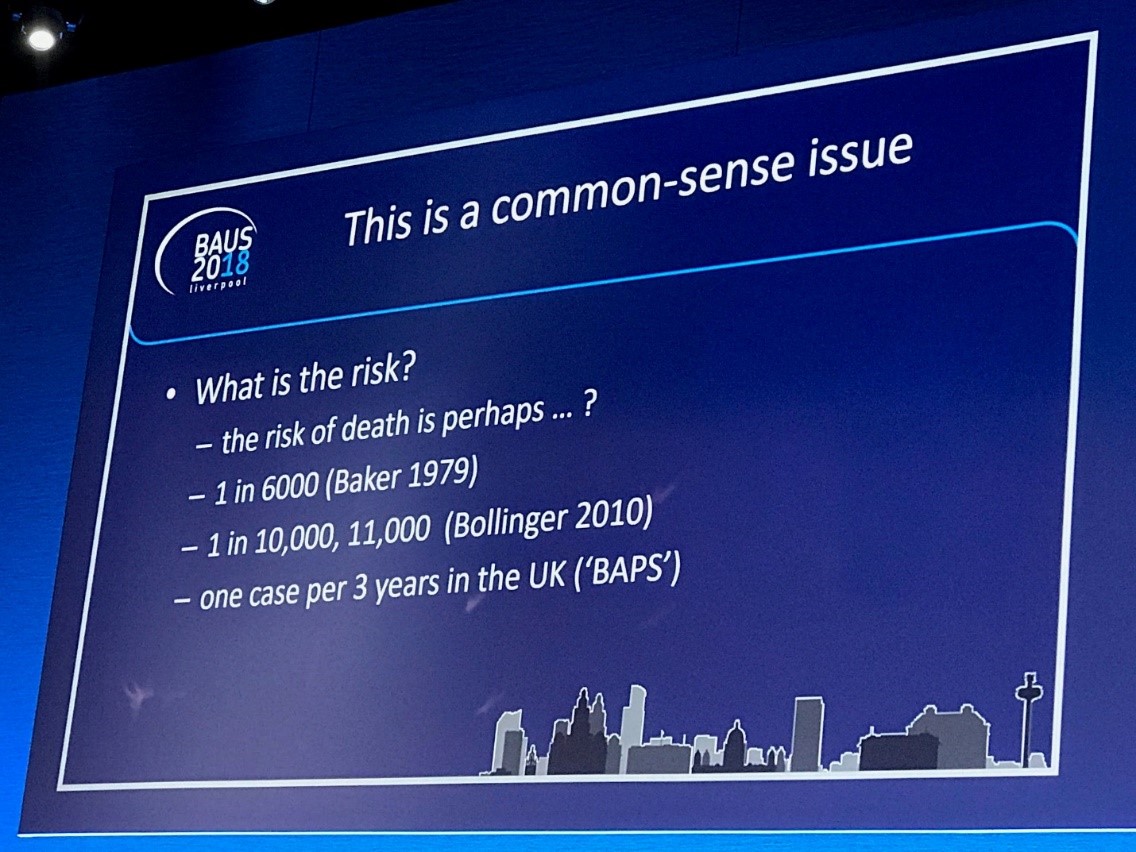

The Day 3 morning session started with what is likely an original debate topic: “Consenting to Death.” The pro/con centered around whether or not every circumcision operation should be consented for the possibility of death. The idea was nominated by Jonathan Glass who also did a Twitter poll on the subject, which was similar to this audience poll—around 90% saying no.

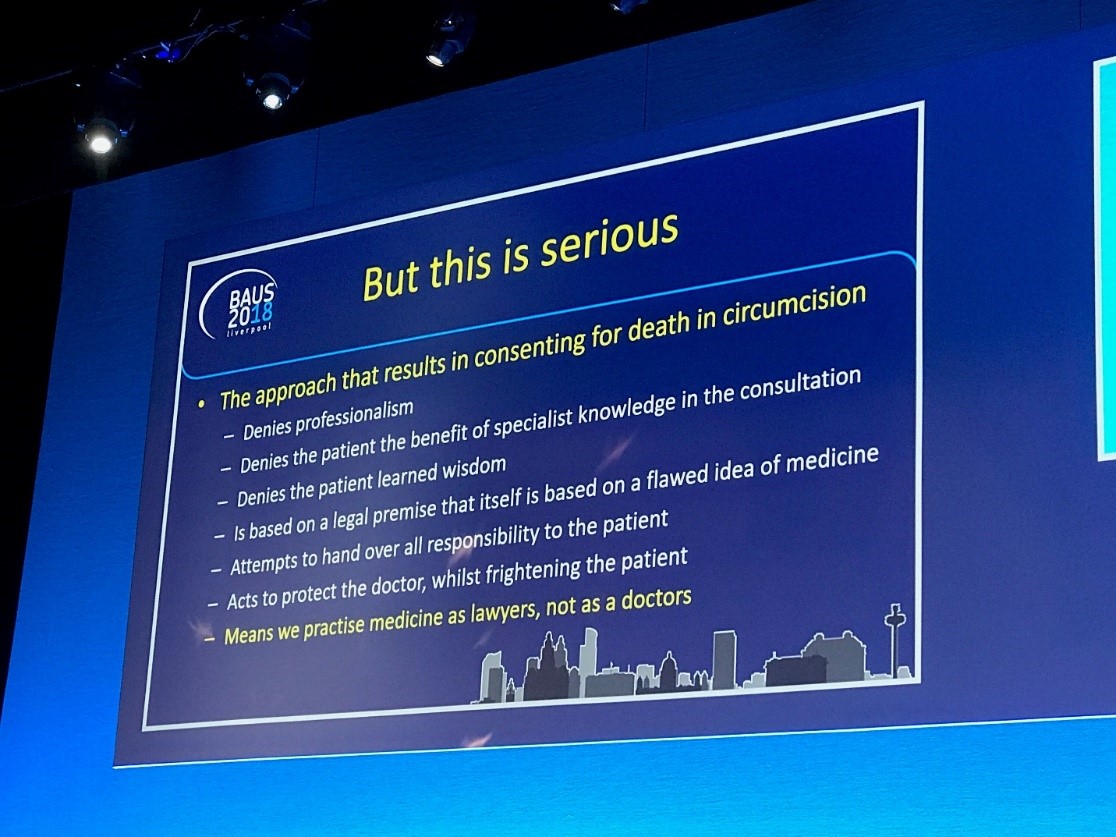

The general flow of the debate was whether or not the rare incidence of a complication should be left off, so as not to alarm/concern the patient with minutia. On the other had, severe complications and death should potentially be consented even if rare.

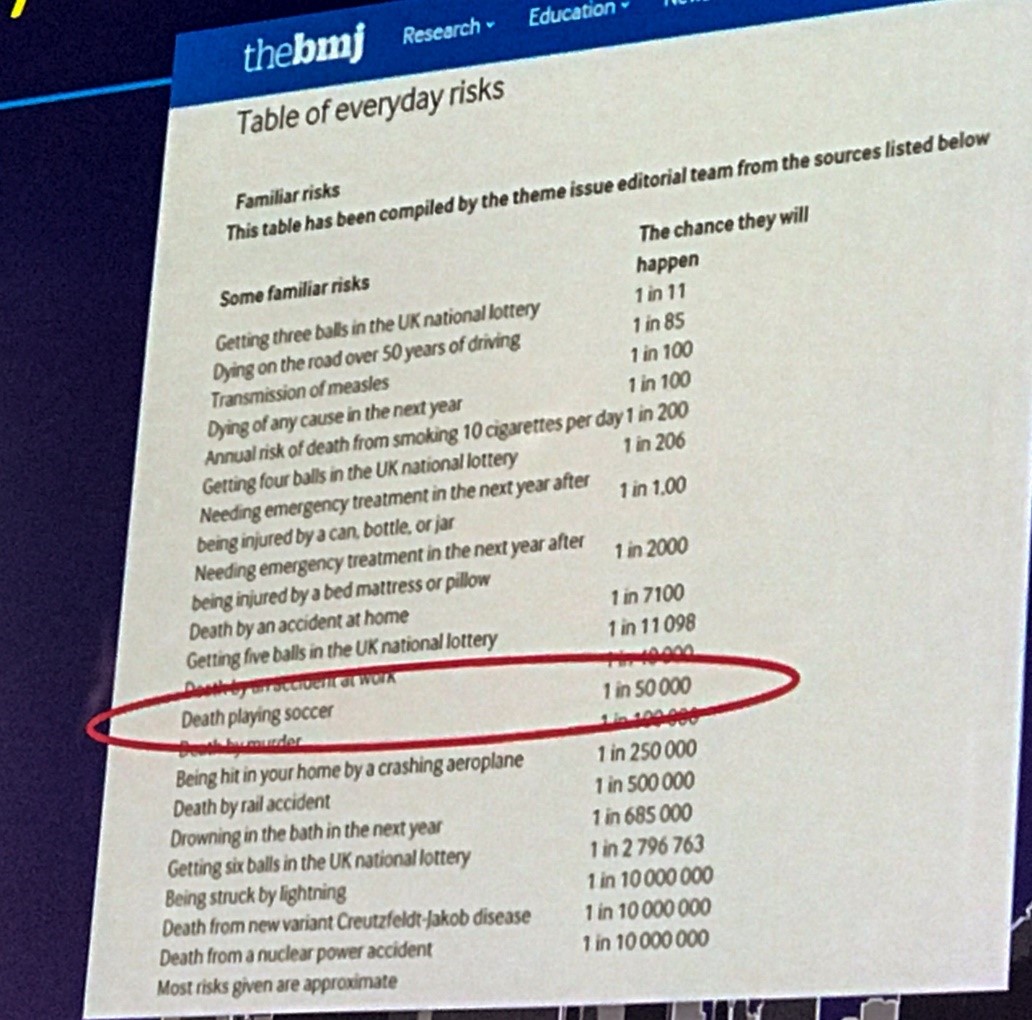

Note the risk of everyday life compared to surgery: soccer was 1: 50,000. Mr. Glass had a nice display on how choices of driving routes to the hospital could affect the risk of dying. Turns out the bus is safest.

At the end of the debate, the voting shifted slightly to around 30% saying they would consent for death for a circumcision.

As Mr. O’Brien asked—do you also have to show the patient some horrific picture of gangrene so they are truly informed as to the risk of serious infection?

My favorite phrase on the serious but rare event is “its low risk, but never zero…perhaps a lightning strike.” Never say “routine surgery,” as that is always what the newspaper says: “ He died after routine surgery.” Routine sounds like zero risk. I must say also that the risk of “bleeding, infection, cardiac event, stroke, and death” is on almost every U.S. hospital template consent. So I think patients are used to it and will not freak out. Also vis-a-vie the Day 2 Blog on Dr. Wachter’s talk, an unintended consequence of the EPIC EMR is that we rarely print consents for patient review—rather we shows them on a screen and they digitally sign. But I bet they read the details less often than before. Oddly, they are not able to view their consents with their personal accounts, yet they can read clinic notes, diagnostics, imaging, path ,etc. Need a solution here.

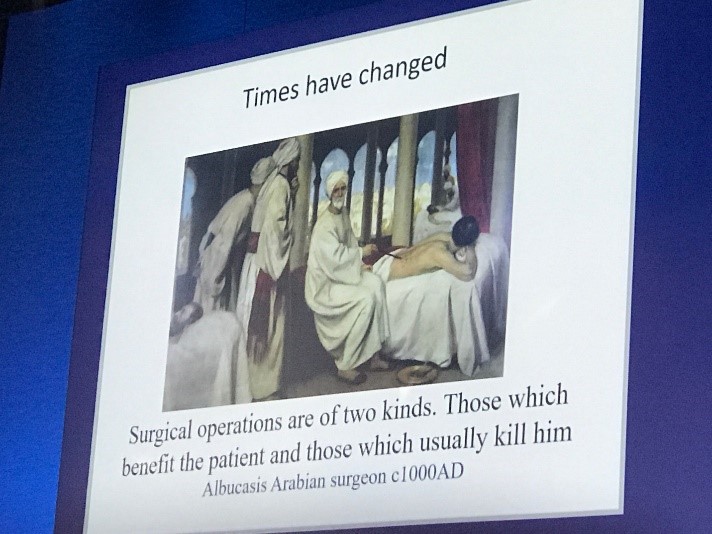

Always good to have some humor in the slides.

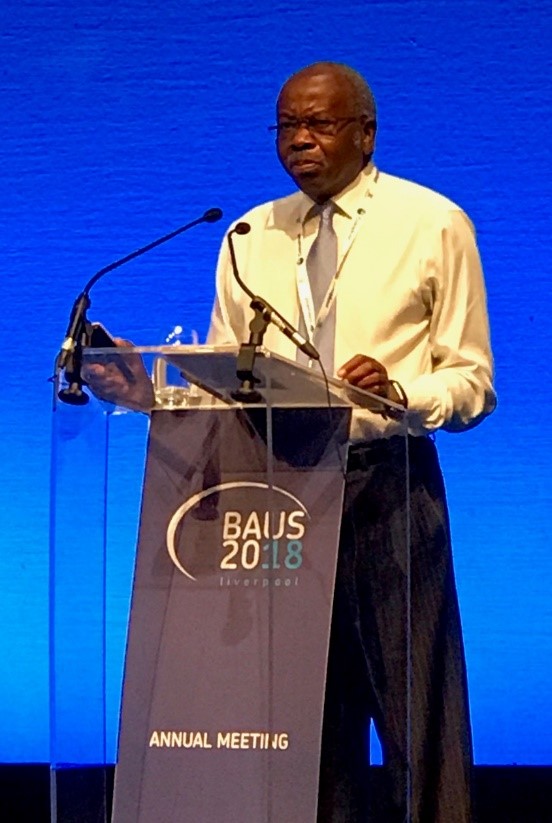

Next, we heard a lecture from a truly unique individual. Mr. David Sellu gave us his personal account of how he was brought before a criminal court for manslaughter when a patient had a bowel perforation after a knee operation—he was in call coverage. He served time but won his appeals to drop charges and clear his name. I’m sure there were errors in the case, but in the U.S. this would likely have been a malpractice/civil court case and the hospital would have been co-defendant (system errors). Roger Kirby has tweeted the progress of this case for years, so it was interesting to hear from him personally.

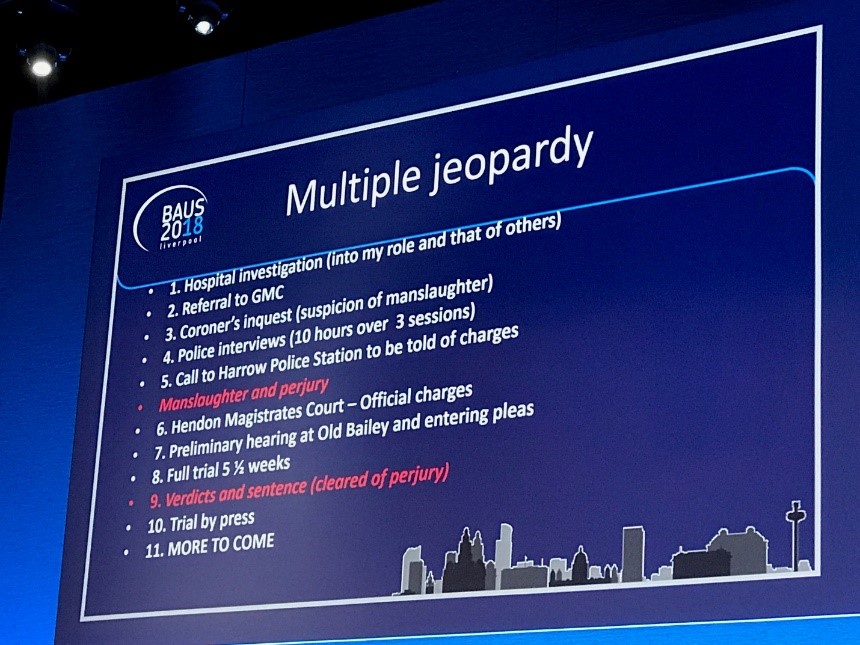

Look at the multiple layers of jeopardy his case took him through over a 6 year period.

Here is a link to a previous blog on the case:

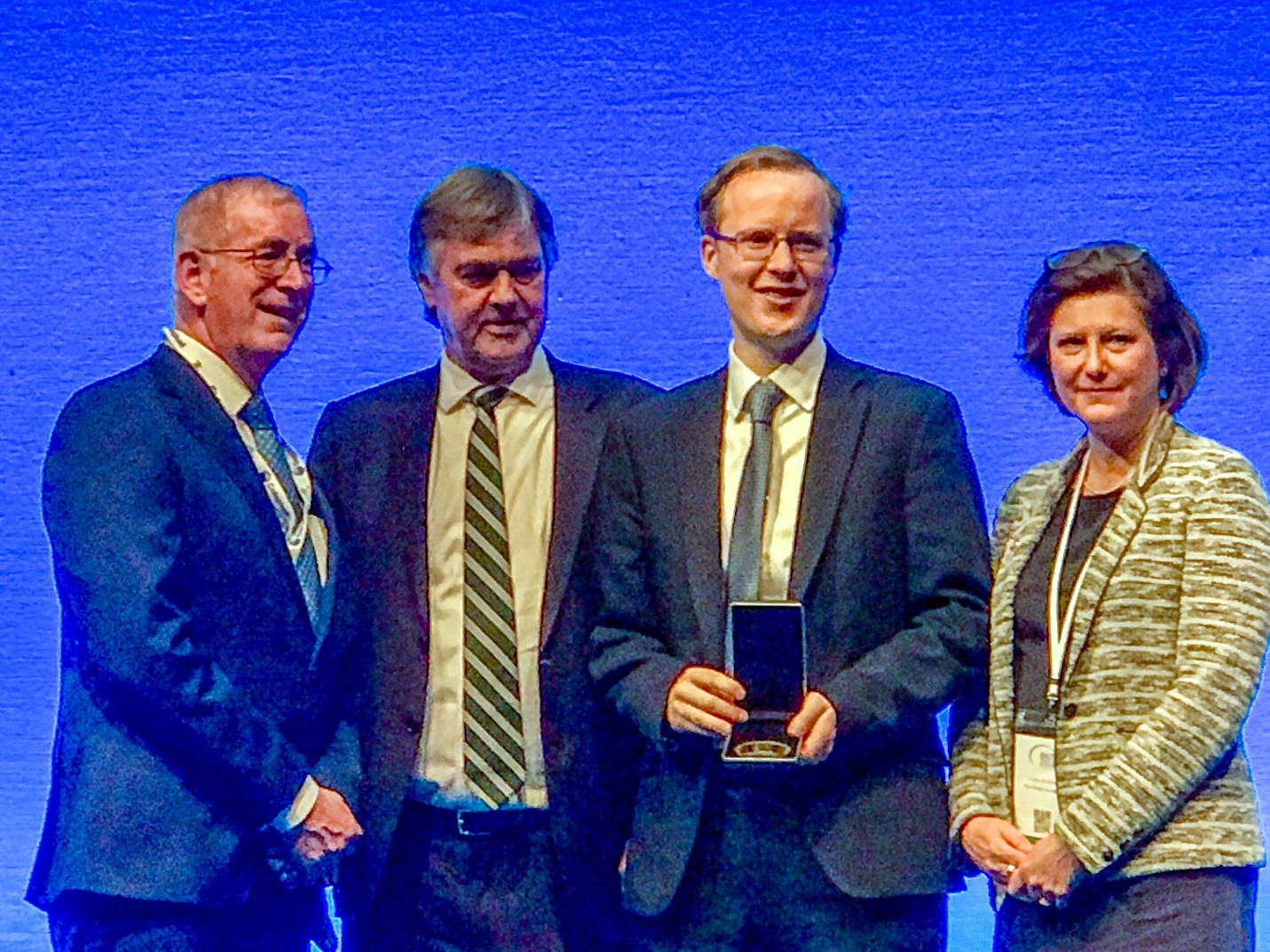

The Urology Foundation sponsored a session. They recognized a recent research scholarship awarded to Mr. David Eldred-Evans “The PROSTAGRAM trial: a prospective cross-sectional study assessing the feasibility of novel imaging techniques to screen for prostate cancer.

Roger Kirby then gave a guest lecture on his personal journal with prostate cancer as a surgeon and patient. He highlighted his actual biopsy specimens and RP path. He is 5 years disease free. He also showed some great nostalgia as he was being interviewed >20 years ago at the launch of Proscar to the market. He had 2 interviewers trying to gang up on him on conflict of interest and trying to make the drug sound toxic. I wonder how he would have handled those two in this era.

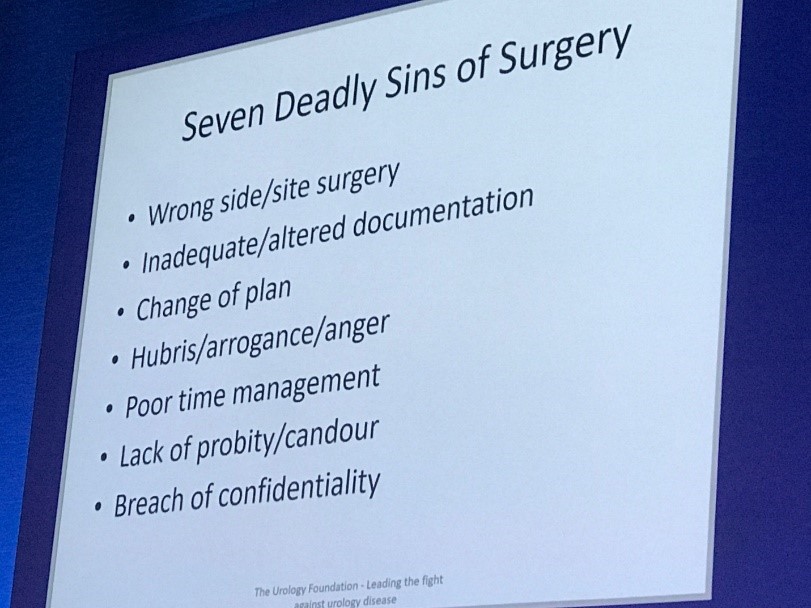

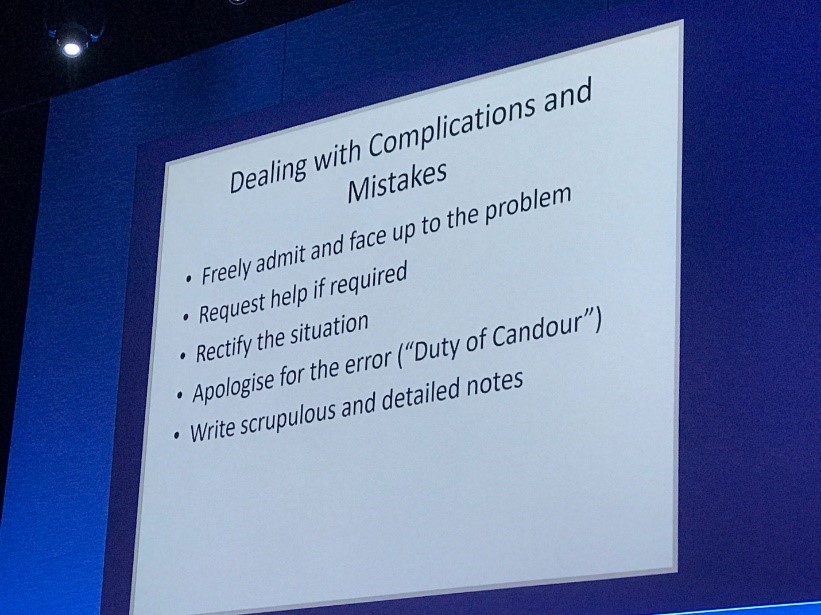

Some highlights of his slides on advice to surgeons. Thanks for all you do Roger.

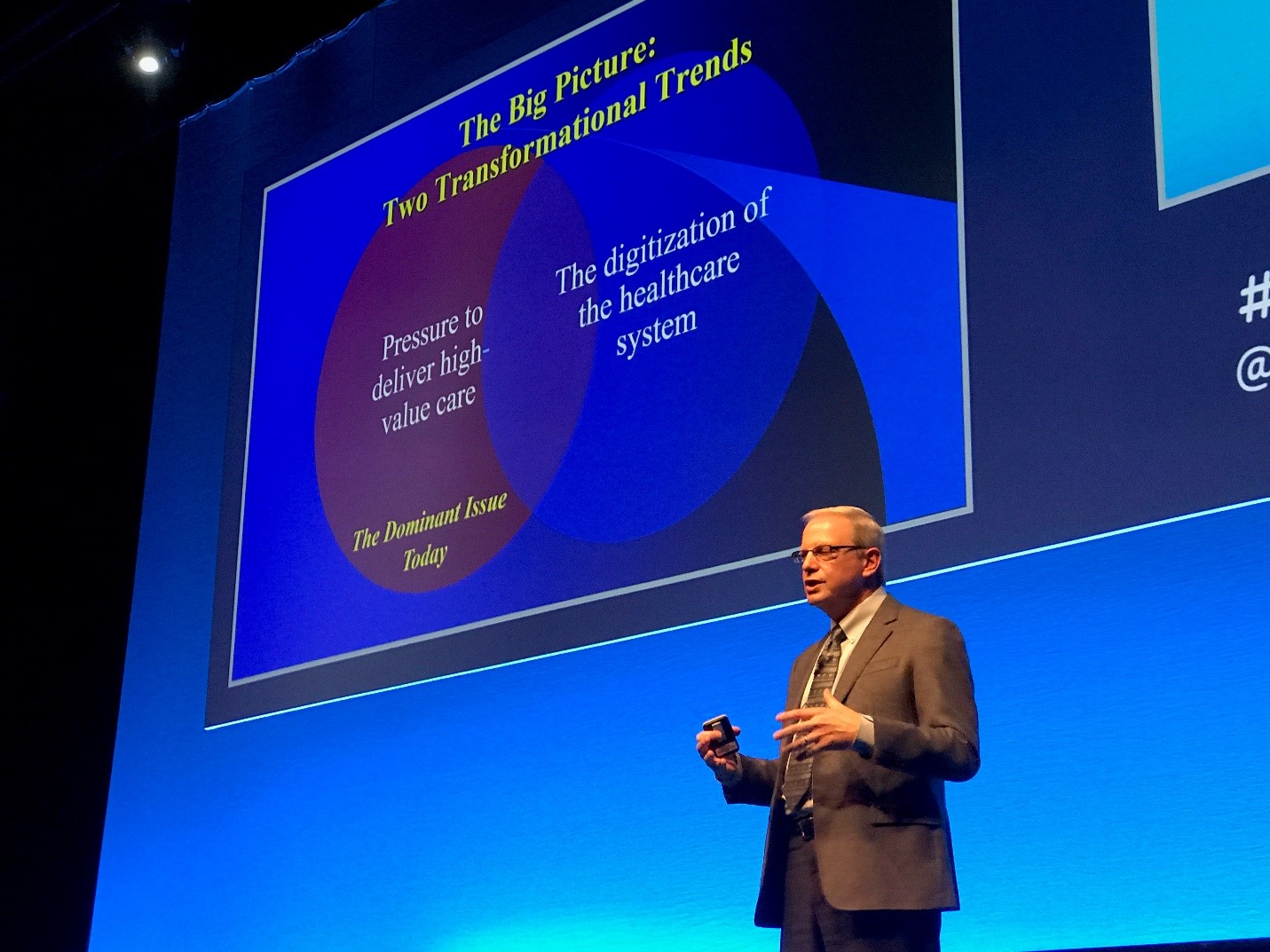

Finally, there was an interesting session on the Global practice of urology with emphasis on training pathways and what has changed over the decade. Alan Partin presented his department’s approach to urology training at Johns Hopkins and the US perspective. James N’Dow outlined how diverse urologic training and credentialing is organize across Europe. Sanjay Kulkarni gave in Indian perspective—noteworthy that the urologist does not have such constraining credentialing pathways, and often will have private practice across multiple hospitals. He has attended over 60 and now owns one for his urethroplasty cases. Times are changing globally for urologic training, and Dr. Partin summed it up well by pointing out that the process of training is highly scrutinized now and seemingly higher priority than the final trained product. Does anyone think that a urology graduate in 2018 is better trained than 1998?

Ok—time to get back to work in Houston.

John W. Davis, MD, FACS

Associate Editor, BJUI.