Patient with De Novo Adenosquamous Carcinoma of the Prostate

We report a case of ASC arising spontaneously in a 54 year old male with no previous risk factors.

Authors: Love, Matthew; Storey, Barckley; Alatassi, Houda; Tonkin, Jeremy

Corresponding Author: Love, Matthew

Abstract

Primary adenosquamous cell carcinoma of the prostate (ASC) is an exceedingly rare and aggressive form of prostate cancer, making up <1% of all diagnoses. Since its initial description by Thompson in 1942, there have been fewer than 30 cases reported in the literature. Recent reports of age-adjusted incidence rates of ASC have been shown to be around 0.03 cases per million people per year, making it less prevalent than pure squamous cell carcinoma, an exceedingly rare subtype in itself. While the majority of these tend to arise subsequent to endocrine or radiation treatment with squamous differentiation, approximately one-third of cases have arisen in a de novo setting. We report a case of ASC arising spontaneously in a 54 year old male with no previous risk factors.

Introduction

Primary adenosquamous cell carcinoma of the prostate (ASC) is an exceedingly rare and aggressive form of prostate cancer. Since its initial description by Thompson in 1942, there have been fewer than 30 cases reported in the literature [1]. While the majority of these tend to arise subsequent to endocrine or radiation treatment with squamous differentiation, approximately one-third of cases have arisen in a de novo setting [2]. We report a case of ASC arising spontaneously in a 54 year old African American male with no previous risk factors.

Case Report

A 54 year old African American male was referred to the University of Louisville Department of Urology following detection of an elevated PSA of 20 ng/mL on annual screening. He denied hematuria, dysuria, ejaculatory issues, or lower urinary tract symptoms at the time of presentation. Past medical history was noncontributory and there was no history of prostate cancer or any other malignancies in his family. On digital rectal examination the patient was noted to have a 40 gram prostate that was firm, non-tender, and with no discernible nodules. Repeat PSA was obtained and was found to be 46.7 ng/mL and he was subsequently scheduled for an ultrasound guided prostate biopsy.

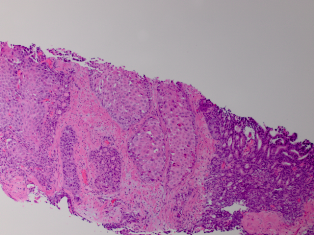

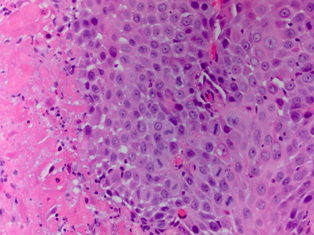

Standard 12 core template prostate biopsy revealed adenosquamous carcinoma of the prostate, Gleason 4+4=8 in 7/12 cores and involving more than 50% of each core (See Figure 1 and Figure 2). As a result, an extensive metastatic workup was performed. Bone scan revealed multiple metastatic sites including the patient’s right rib, pubic symphysis, and iliac crest. CT abdomen/pelvis was obtained showing extensive retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. Chest X-ray was negative for disease.

Due to the extensive metastatic nature of the disease, the patient opted for hormone deprivation therapy and an elective orchiectomy was performed. He was then referred to medical oncology for chemotherapeutic intervention.

Discussion/Conclusion

ASC of the prostate is among one of the rarest and most aggressive subtypes of prostate cancer making up <1% of all diagnoses [3]. Recent reports of age-adjusted incidence rates of ASC have been shown to be around 0.03 cases per million people per year, making it less prevalent than pure squamous cell carcinoma, an exceedingly rare subtype in itself [4].

The underlying mechanism for the progression and development of ASC is unknown and debated; however, most theories contend that differentiation is triggered by the various treatment modalities rather than de novo development [5]. While over two thirds of the cases of ASC originate in patients with previously diagnosed adenocarcinoma of the prostate who have been treated with additional endocrine/radiation therapy, it is extremely rare to find a primary case of this particular subtype[5]. While some believe that hormonal treatment and radiotherapy induce squamous metaplasia in the glandular cells of adenomatous prostate cancer, others contend that ASC develops de novo from divergent differentiation from epithelial stem cell lines within the prostatic cells [6] [7]. Due to the infrequent occurrence of this disease there are very few available studies to examine the mechanism behind this metaplastic process and research is currently undergoing.

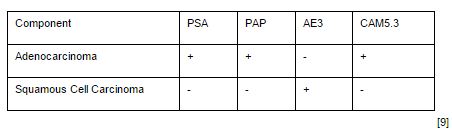

ASC is defined by the presence of both glandular and squamous components on histological examination. The squamous elements of ASC constitute on average of 40% of the tumor volume but can range anywhere from 5-95% [8]. This wide range of cell types is reflected in ASC variability through immunohistochemical staining. Stains such as PSA, PSAP, and low molecular weight keratin (CAM5.3) are commonly found only in the glandular components of ASC and therefore patients with a large squamous fraction can have normal serum levels of PSA, possibly further delaying diagnosis [3]. Similarly, the squamous portion can stain positive for high molecular weight keratin (AE3), but this can vary depending on the amount of tissue that has squamous components involved (See Table 1) [9]. Additionally, glandular components have a tendency to be more high grade with an average Gleason score of >6, however, this is also a controversial point as some have suggested that Gleason scoring should not be applied to this subtype [8].

ASC tends to follow the traditional metastatic pathways similar to adenocarcinoma of the prostate, starting with local invasion and then spreading to bone and other distant soft tissue sites. However, one notable difference is that unlike standard prostatic adenocarcinoma, bone metastatic sites are characteristically osteolytic rather than osteoblastic in nature [3].

ASC is an extremely aggressive subtype of prostate cancer and in most cases is found to have widely metastasised at time of diagnosis, suggesting that this disease has a tendency to disseminate early. Most cases reported in the literature presented in individuals who were found to be in urinary retention and the pathological diagnosis was made on TURP specimens [8]. The disease is highly resistant to radiation and chemotherapy and in those individuals fortunate enough to be diagnosed early with localized/regional disease, prostatectomy shows some survival advantage [2]. It is not clear whether hormone ablation is an effective treatment modality, as some authors suggest an early response while others have noted that patients are refractory to hormone deprivation. Long term survival is extremely poor. Wang et al, evaluating SEER data and isolating for patients with an ASC diagnosis, found that the median cancer specific survival was 16 months [2]. For patients who presented with distant disease, the 6 month survival rate was only 20% with all dying within one year of diagnosis.

While literature on the subject of ASC is limited, it appears that the best initial treatment for this particular type of cancer is aggressive surgical intervention in patients with regionally restricted disease. However, due to the highly aggressive nature of this disease in most cases, such as this one, patients present with widely disseminated disease and are relegated to a regimen of hormone ablation and chemotherapy. Currently there are no recommended chemotherapeutic regimens targeted at ASC.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

References

1. Thompson GJ. Transurethral resection of malignant lesions of the prostate gland. JAMA, 1942;120: 1105-9.

2. Wang J, Wang FW, LaGrange CA, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of 25 patients with primary adenosquamous cell carcinoma of the prostate. Rare Tumors, 2010; 2(3): e47.

3. Humphrey PA. Histological variants of prostatic carcinoma and their significance. Histopathology, 2012; 60(1): 59-74.

4. Marcus DM, Goodman M, Jani AB, et al. A comprehensive review of incidence and survival in patients with rare histological variants of prostate cancer in the United States from 1973 to 2008. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Disease, 2012. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2012.4.

5. Mazzucchelli R, Lopez-Beltran A, Cheng L, et al. Rare and unusual histological variants of prostatic carcinoma: clinical significance. BJU International, 2008; 102: 1369–1374.

6. Baydar DE, Kosemehmetoglu K, Akdogan B, et al. Prostatic Adenosquamous Carcinoma Metastasizing to Testis. The Scientific World Journal, 2006; 6: 2491–2494.

7. Egilmez T, Bal N, Guvel S, et al. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the prostate. Int J Urol, 2005; 12(3): 319-21.

8. Parwani AV, Kronz JD, Genega EM, et al. Prostate carcinoma with squamous differentiation: an analysis of 33 cases. Am J Surg Pathol, 2004; 28(5): 651-7.

9. Gattuso P, Carson HJ, Candel A, et al. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the prostate. Hum Pathol, 1995; 26(1): 123-6.

Table 1

Immunohistochemicalstaining patterns of adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas of the prostate.

Date added to bjui.org: 14/12/2012

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-087-web