Article of the week: The ProtecT trial: analysis of the patient cohort, baseline risk stratification and disease progression

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to this post, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community and a podcast produced by on of our resident podcasters. Please use the comment buttons below to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, we recommend this one.

The ProtecT trial: analysis of the patient cohort, baseline risk stratification and disease progression

Richard J. Bryant*, Jon Oxley†, Grace J. Young‡§, Janet A. Lane‡§, Chris Metcalfe‡§, Michael Davis‡, Emma L. Turner‡, Richard M. Martin‡, John R. Goepel¶, Murali Varma**, David F. Griffiths**, Ken Grigor††, Nick Mayer‡‡, Anne Y. Warren§§, Selina Bhattarai¶¶, John Dormer‡‡, Malcolm Mason***, John Staffurth†††, EleanorWalsh‡, Derek J. Rosario‡‡‡, James W.F. Catto‡‡‡, David E. Neal*§§§, Jenny L.Donovan‡¶¶¶, Freddie C. Hamdy* and for the ProtecT Study Group1

*Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, †Department of Cellular Pathology, North Bristol NHS Trust, ‡Bristol Medical School, §The Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration, University of Bristol, Bristol, ¶Department of Pathology, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield, **Department of Pathology, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, ††Department of Pathology, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, ‡‡Department of Pathology, University of Leicester, Leicester, §§Department of Pathology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, ¶¶Department of Pathology, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, ***School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, †††Division of Cancer and Genetics, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, ‡‡‡Academic Urology Unit, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, §§§Academic Urology Group, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, and ¶¶¶National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, Bristol, UK

Abstract

Objective

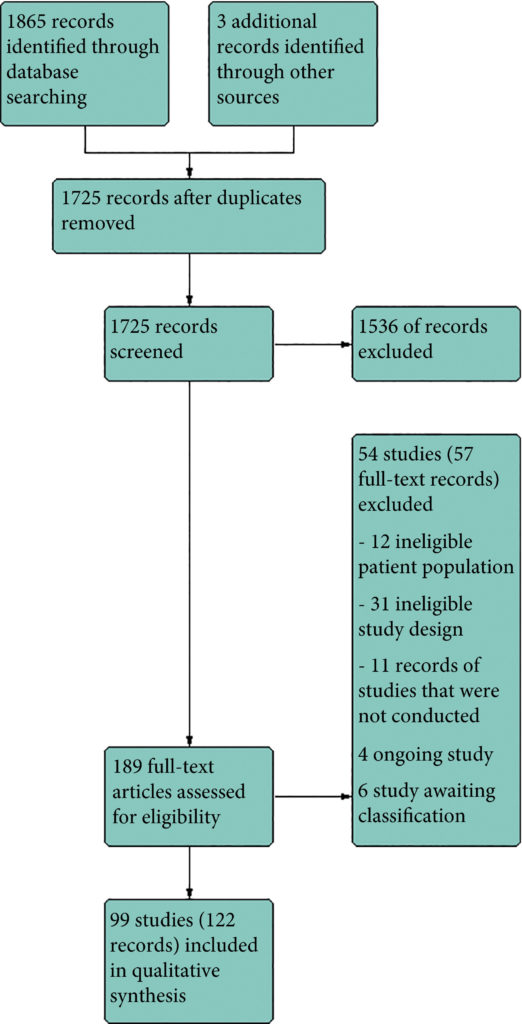

To test the hypothesis that the baseline clinico‐pathological features of the men with localized prostate cancer (PCa) included in the ProtecT (Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment) trial who progressed (n = 198) at a 10‐year median follow‐up were different from those of men with stable disease (n = 1409).

Patients and Methods

We stratified the study participants at baseline according to risk of progression using clinical disease stage, pathological grade and PSA level, using Cox proportional hazard models.

Results

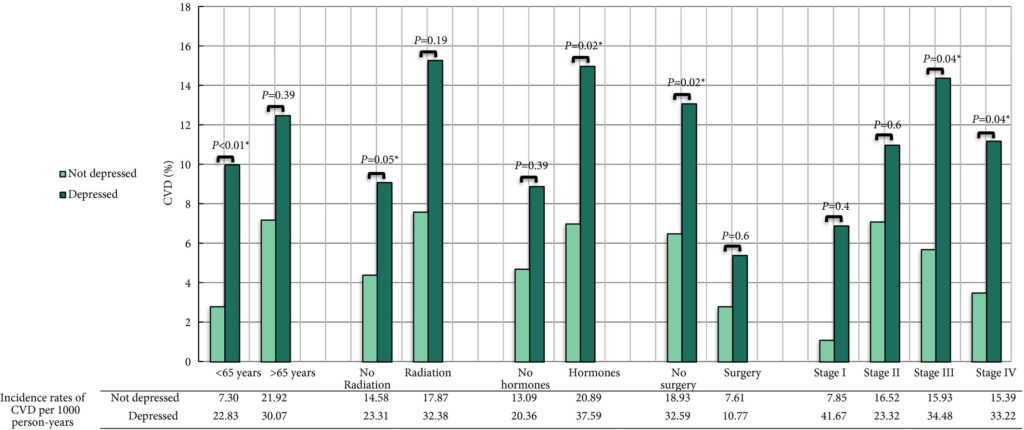

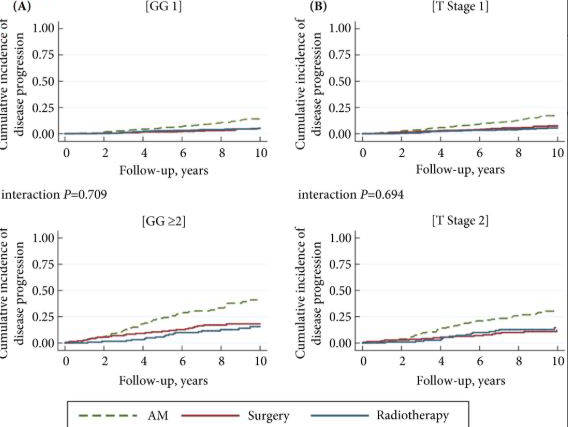

The findings showed that 34% of participants (n = 505) had intermediate‐ or high‐risk PCa, and 66% (n = 973) had low‐risk PCa. Of 198 participants who progressed, 101 (51%) had baseline International Society of Urological Pathology Grade Group 1, 59 (30%) Grade Group 2, and 38 (19%) Grade Group 3 PCa, compared with 79%, 17% and 5%, respectively, for 1409 participants without progression (P < 0.001). In participants with progression, 38% and 62% had baseline low‐ and intermediate‐/high‐risk disease, compared with 69% and 31% of participants with stable disease (P < 0.001). Treatment received, age (65–69 vs 50–64 years), PSA level, Grade Group, clinical stage, risk group, number of positive cores, tumour length and perineural invasion were associated with time to progression (P ≤ 0.005). Men progressing after surgery (n = 19) were more likely to have a higher Grade Group and pathological stage at surgery, larger tumours, lymph node involvement and positive margins.

Conclusions

We demonstrate that one‐third of the ProtecT cohort consists of people with intermediate‐/high‐risk disease, and the outcomes data at an average of 10 years’ follow‐up are generalizable beyond men with low‐risk PCa.