Editorial: All for one, one for all: is centralisation the way to go?

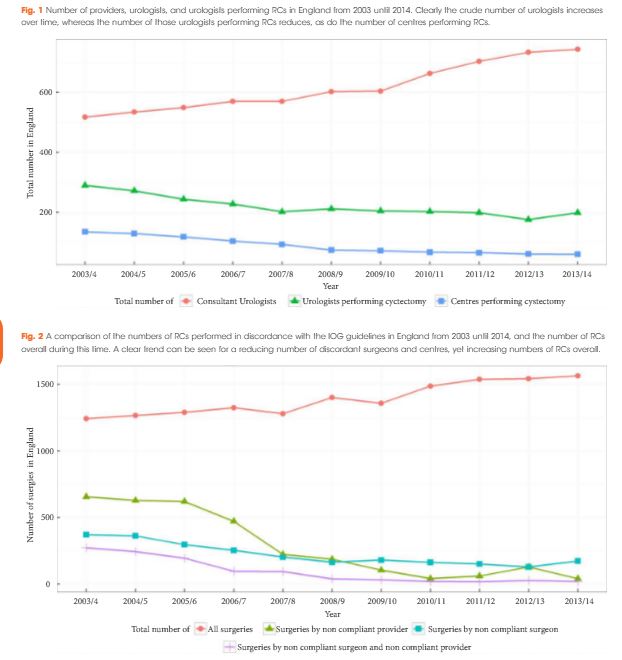

The need to centralise complex surgical procedures in large centres remains at the core of many health policy discussions. Much of the debate is focussed on three main aspects: (i) outcomes, (ii) costs and (iii) accessibility. Gray et al. [1] recently noted that increasing centralisation may be unnecessary for invasive procedures such as nephrectomy and cystectomy. Specifically, they noted almost no difference in outcomes of high‐volume centralised centres and those with lower throughput. Their findings go against most of the current literature on the volume–outcomes relationship, which generally reports a correlation between a hospital’s volume of procedures and improved healthcare outcomes. One could ask what factors specific to their analysis could explain the different observations. For one, the healthcare system in the UK may (and likely) operate in ways different from other European and USA‐based healthcare systems, from which most of the current data are derived. Healthcare in the UK may already be organised in such a way that further centralisation may not improve outcomes, which the authors allude to in their conclusions. Differences in methodology may explain their findings, e.g. their use of multilevel modelling, testing specific incremental volume cutoffs, etc. Outcome selection may play a role as well; length of stay and re‐admissions may vary more according to organisational factors rather than individual surgeon expertise.

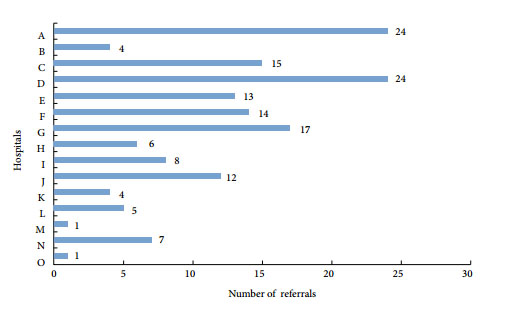

Regardless of their findings, we would argue that there are other tangible benefits to centralisation, which extend well beyond ‘better outcomes’. For instance, the management of the modern oncological, and urological, patient is critically dependent on a multidisciplinary team. The inherent multidisciplinary nature of large centres facilitates patients receiving their entire course of treatment at the same place. This enhances the continuity and efficiency of care, both of which are undoubtedly hampered in small peripheral centres that ultimately depend on referrals to larger facilities for advanced care for the most complex patients.

This ties into yet another major advantage of centralised centres, which is the ease of access to research. For instance, our affiliated cancer centre runs >1100 active clinical trials, 42 of which pertain to advanced urological diseases. Such trials provide access to otherwise unavailable therapies and enhance the production, diffusion, and application of knowledge.

In touting the many benefits of centralisation, one would imagine it comes at a significant cost. While this may have been true in the past, recent data comparing the higher‐volume teaching hospitals to lower‐volume non‐teaching centres suggest that centralisation actually decreases the 30‐day hospital costs and have similar costs at 90 days compared with non‐teaching hospitals [2]. Similar trends were also seen with radical cystectomies [3] and prostatectomies [4], showing that with the major urological procedures, centralisation is cost‐effective with at least the same outcomes as compared to peripheral centres.

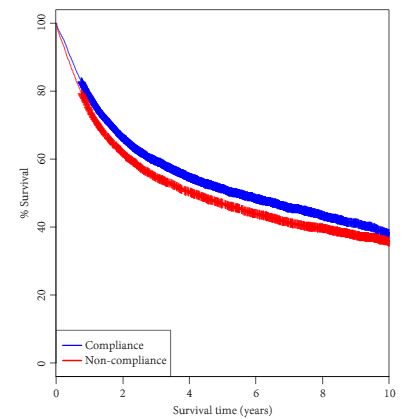

A common objection to centralisation is that it forces many patients to travel long distances and that this in turn could introduce or worsen discrepancies in accessibility to care. If true, this would have profound social and economic consequences for disadvantaged groups, as well as particularly fragile patients. Many centralised centres have developed approaches to ease the burdens of travelling from afar and, if patients can make the journey, the data suggest a survival advantage over those who are treated at peripheral centres. To this end, Vetterlein et al. [5] stratified >700 000 patients by risk class and demonstrated an overall survival benefit in those with all stages of prostate cancer. In the not‐too‐distant future, patient follow‐up can be shifted almost entirely to telemedicine, which can further alleviate travel burdens.

Our aim is not to promote a system of oncological care based solely at centralised hubs. However, to suggest that all care should be distributed equally across all centres seems unrealistic and may have devastating consequences, particularly for those with advanced disease. We strongly advocate the treatment of complex disease at high‐volume, centralised centres and suggest better use of an impartial classification of what constitutes a ‘complex’ disease. Therefore, one answer to this problem is broadly represented by the redistribution of the different surgical procedures amongst the hospitals.

by Daniele Modonutti, Venkat M. Ramakrishnan and Quoc‐Dien Trinh

References

- , , , . Understanding volume‐outcome relationships in nephrectomy and cystectomy for cancer: evidence from the UK Getting it Right First Time programme. BJU Int 2020; 125: 234– 43

- , , , , , . Comparison of costs of care for medicare patients hospitalized in teaching and nonteaching hospitals. JAMA Netw Open 2019; 2: e195229

- , , et al. Impact of surgeon volume on the morbidity and costs of radical cystectomy in the USA: a contemporary population‐based analysis. BJU Int 2015; 115: 713– 21

- , , et al. Redefining and contextualizing the hospital volume‐outcome relationship for robot‐assisted radical prostatectomy: implications for centralization of care. J Urol 2017; 198: 92– 9

- , , et al. Impact of travel distance to the treatment facility on overall mortality in US patients with prostate cancer. Cancer 2017; 123: 3241– 52