Earlier this month at the annual American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting in Chicago, IL, Dr. Karim Fizazi and Dr. Nicholas James (@Prof_Nick_James) presented results from the LATITUDE and STAMPEDE trials, respectively. These randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessed the utility of adding abiraterone acetate (AA) + prednisone to conventional androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) among men with high-risk, hormone-naïve prostate cancer. Since Dr. Charles Huggins’ 1941 Nobel prize winning finding that ADT is highly effective in controlling metastatic prostate cancer, nearly 70 years passed before CHAARTED and STAMPEDE demonstrated in 2015 that the addition of docetaxel to ADT prolongs survival in men with high volume metastatic prostate cancer. The de novo metastatic prostate cancer global incidence is striking: 3% in the US and rising, 6% across Europe, 4-10% in Latin America, and nearly 60% in Asia-Pacific. Historically, ADT has been standard of care, however most men with metastases progress to metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) driven by the reactivation of androgen receptor (AR) signaling. The rationale for adding AA + prednisone to ADT for metastatic hormone-naïve prostate cancer patients is threefold: (i) the mechanism of resistance to ADT may develop early, (ii) ADT alone does not inhibit androgen synthesis by the adrenal glands or prostate cancer cells, and (iii) AA + prednisone improves overall survival (OS) in mCRPC patients and reduces tumor burden in high-risk, localized prostate cancer.

Earlier this month at the annual American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting in Chicago, IL, Dr. Karim Fizazi and Dr. Nicholas James (@Prof_Nick_James) presented results from the LATITUDE and STAMPEDE trials, respectively. These randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessed the utility of adding abiraterone acetate (AA) + prednisone to conventional androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) among men with high-risk, hormone-naïve prostate cancer. Since Dr. Charles Huggins’ 1941 Nobel prize winning finding that ADT is highly effective in controlling metastatic prostate cancer, nearly 70 years passed before CHAARTED and STAMPEDE demonstrated in 2015 that the addition of docetaxel to ADT prolongs survival in men with high volume metastatic prostate cancer. The de novo metastatic prostate cancer global incidence is striking: 3% in the US and rising, 6% across Europe, 4-10% in Latin America, and nearly 60% in Asia-Pacific. Historically, ADT has been standard of care, however most men with metastases progress to metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) driven by the reactivation of androgen receptor (AR) signaling. The rationale for adding AA + prednisone to ADT for metastatic hormone-naïve prostate cancer patients is threefold: (i) the mechanism of resistance to ADT may develop early, (ii) ADT alone does not inhibit androgen synthesis by the adrenal glands or prostate cancer cells, and (iii) AA + prednisone improves overall survival (OS) in mCRPC patients and reduces tumor burden in high-risk, localized prostate cancer.

LATITUDE

LATITUDE was conducted at 235 sites in 34 countries in Europe, Asia-Pacific, Latin America, and Canada. The objectives of the study were to evaluate the addition of AA + prednisone to ADT on clinical benefit in men with newly diagnosed, high-risk, metastatic hormone-naïve prostate cancer. Patients were stratified by the presence of visceral disease (yes/no) and ECOG performance status (0, 1 vs 2) and then randomized 1:1 to either ADT + AA (1000 mg daily) + prednisone (5 mg) (n=597) or ADT + placebo (n=602). The co-primary endpoints were OS and radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS). Secondary endpoints included time to: (i) pain progression, (ii) PSA progression, (iii) next symptomatic skeletal event, (iv) chemotherapy, and (v) subsequent prostate cancer therapy. The study was powered to detect an HR of 0.67 and 0.81 in favor of AA for rPFS and OS, respectively.

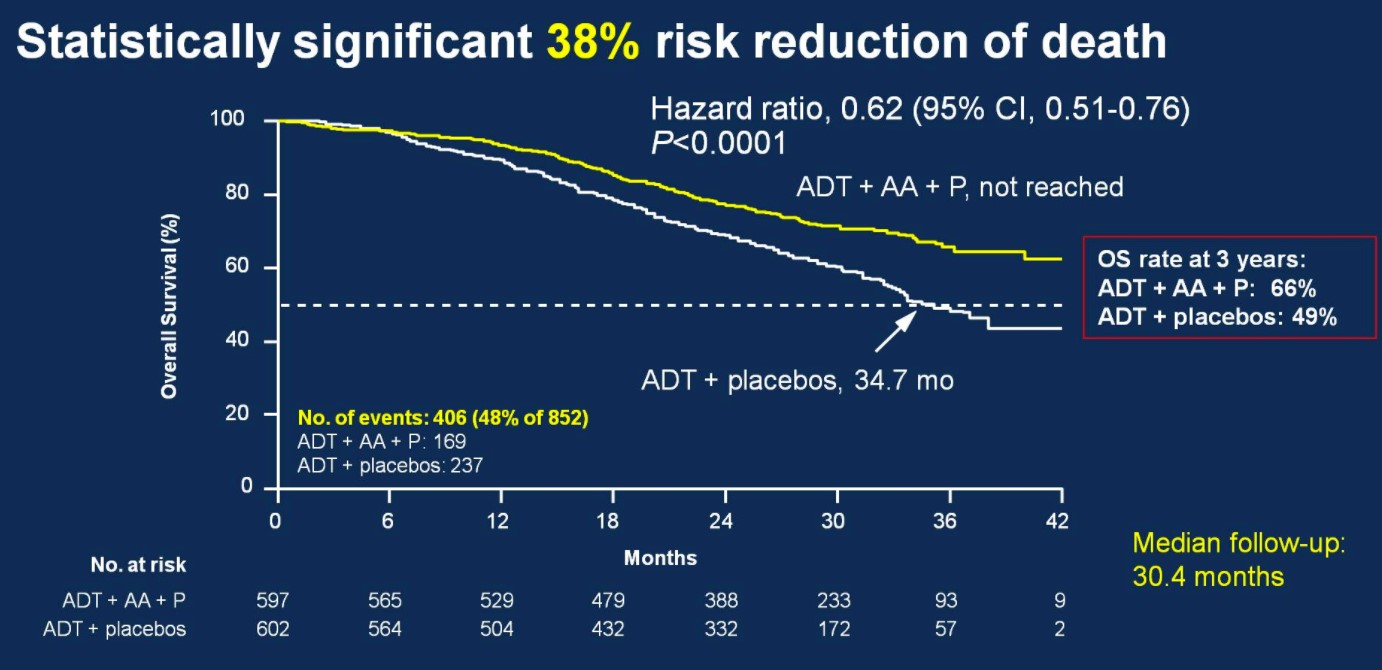

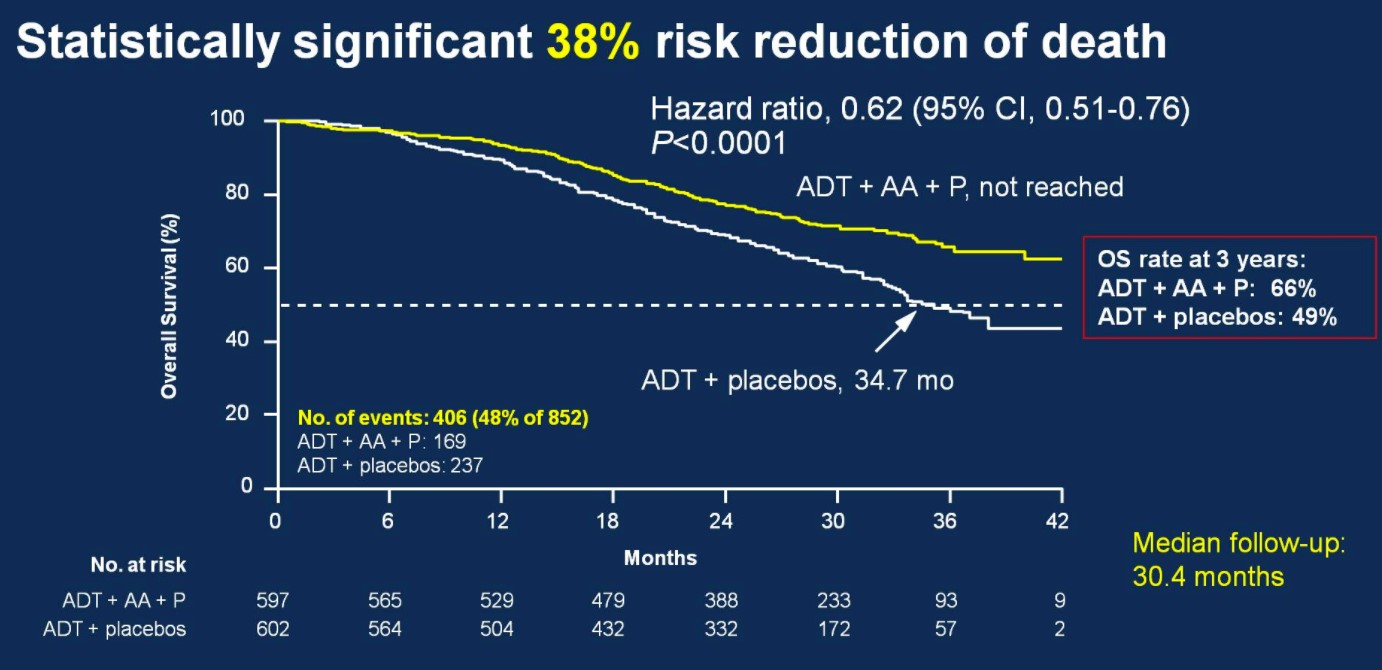

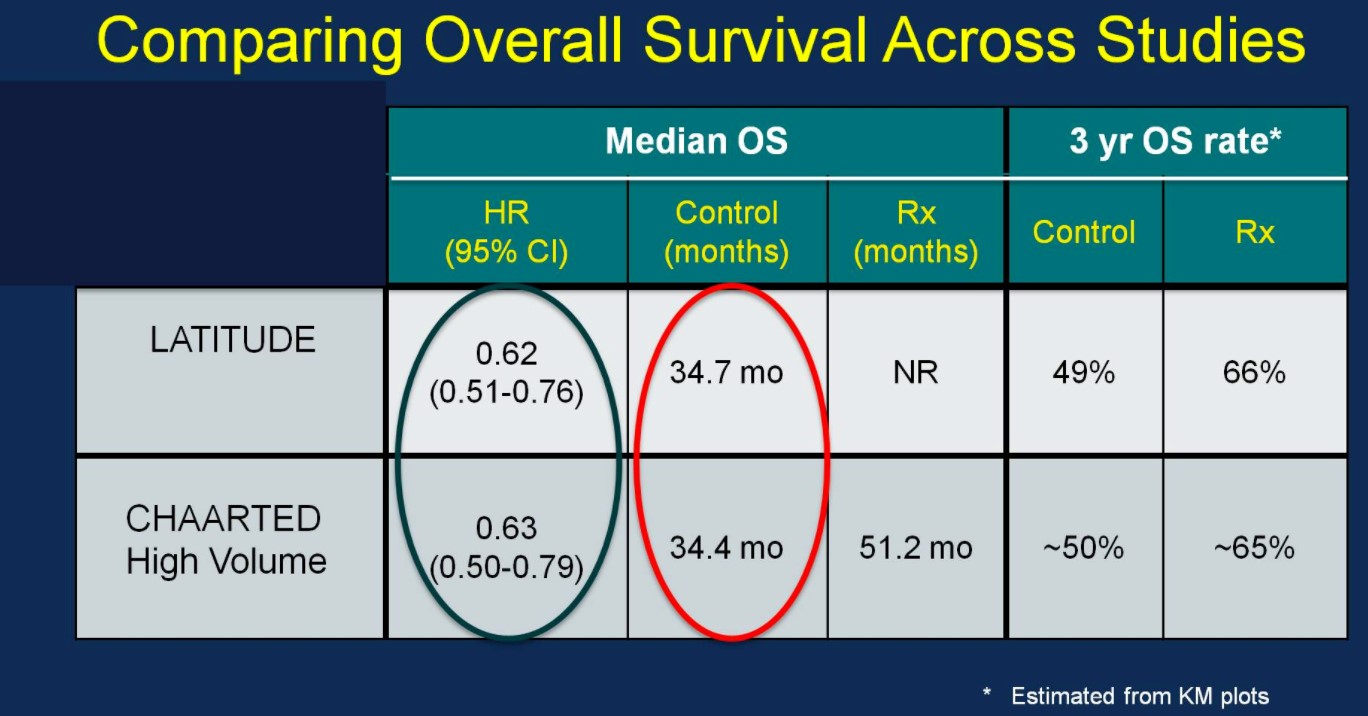

Over a median follow-up of 30.4 months, patients treated with ADT + AA + prednisone had a 38% risk reduction of death (HR 0.62, 95%CI 0.51-0.76) compared to ADT + placebo.

Median OS was not yet reached in the ADT + AA + prednisone arm compared to 34.7 months in the ADT + placebo arm. OS rates at 3 years for the ADT + AA + prednisone arm was 66%, compared to 49% in the ADT + placebo arm. This OS benefit was consistently favorable across all subgroups including ECOG 0 and 1-2, visceral metastases, Gleason ≥8 disease, and bone lesions >10.

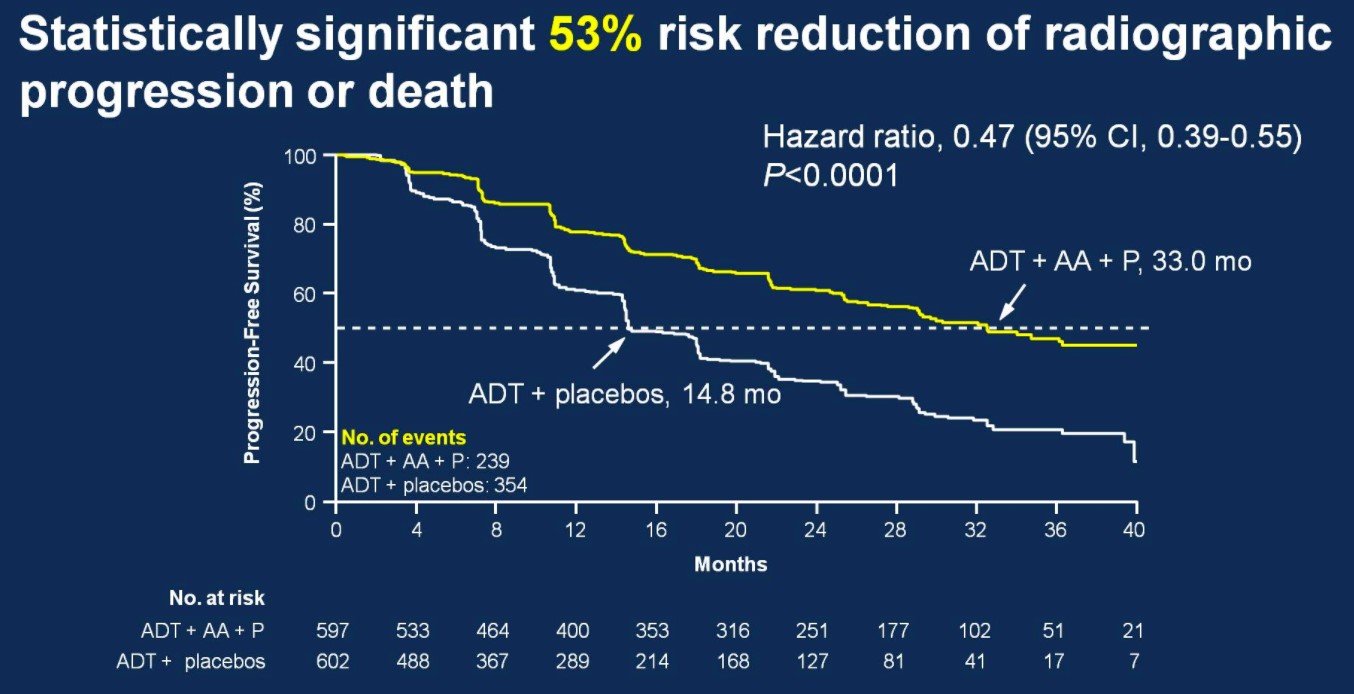

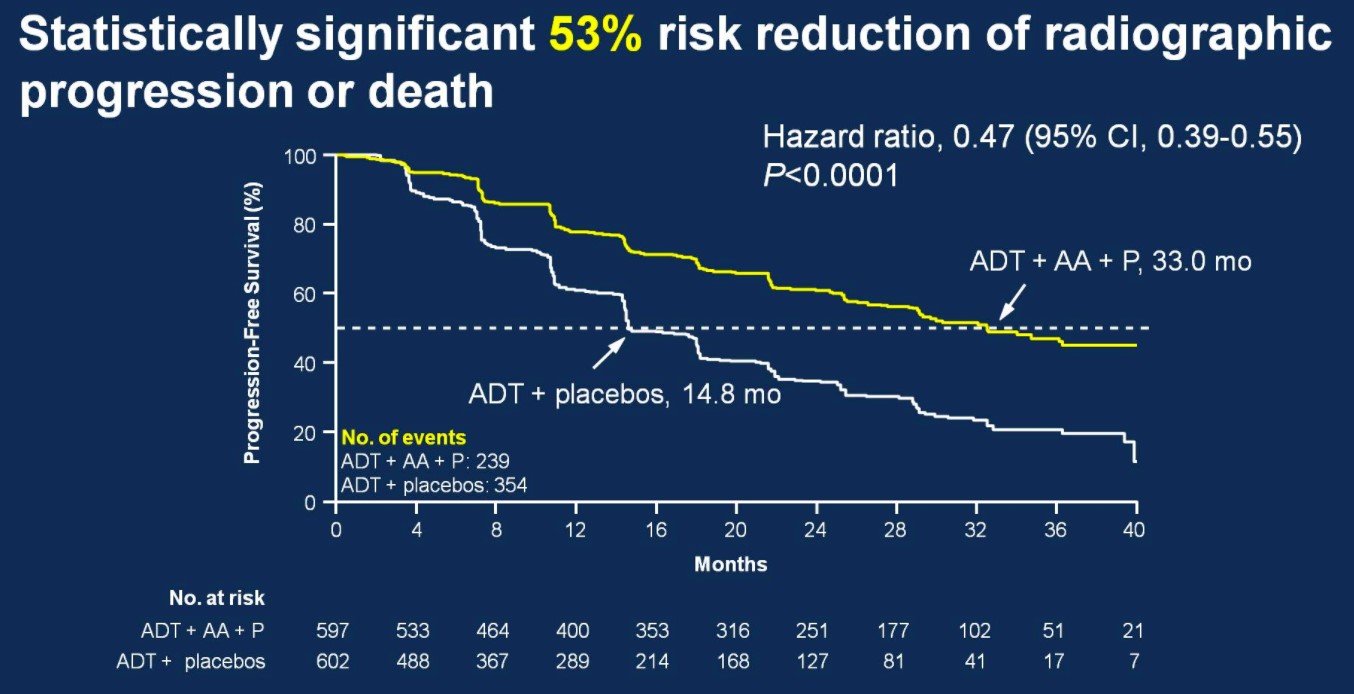

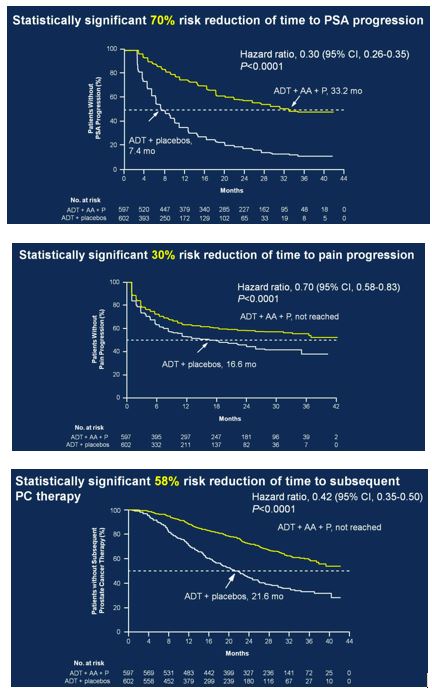

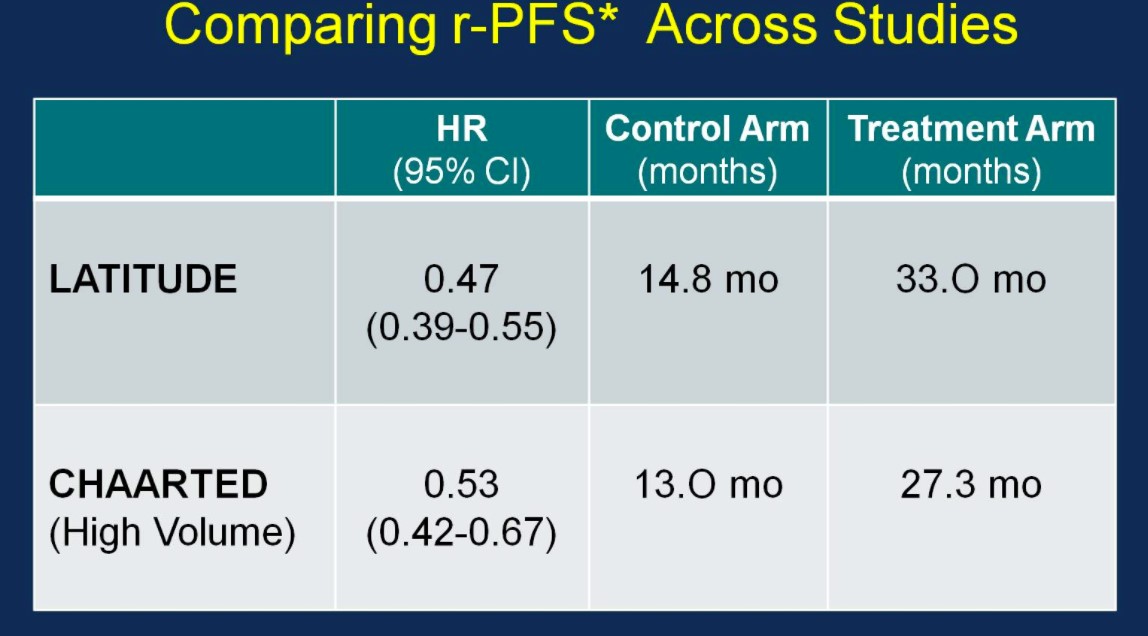

There was also 53% risk of reduction of radiographic progression or death for patients treated with ADT + AA + prednisone (median 33.0 months; HR 0.47, 95%CI 0.39-0.55) compared to ADT + placebo (14.8 months).

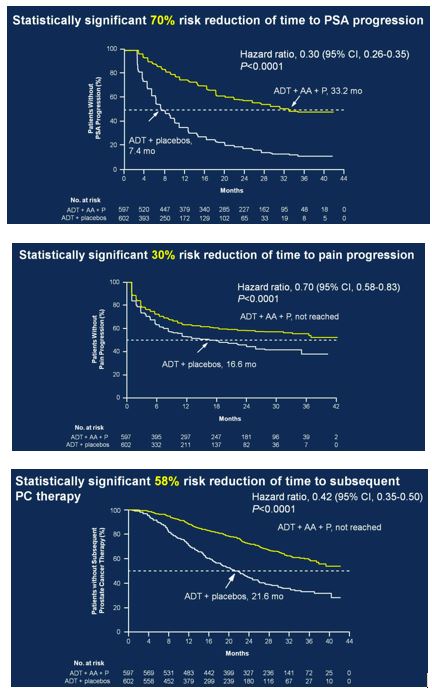

Secondary endpoints showed statistically significant improvement for ADT + AA + prednisone, including time to PSA progression (HR 0.30, 95%CI 0.26-0.35), time to pain progression (HR 0.70, 95%CI 0.58-0.83), time to next symptomatic skeletal event (HR 0.70, 95%CI 0.54-0.92), time to chemotherapy (HR 0.44, 95%CI 0.35-0.56), and time to subsequent prostate cancer therapy (HR 0.42, 95%CI 0.35-0.50).

Secondary to the results presented at ASCO, the study was discontinued after the first interim analysis. Adverse events were comparable in the two groups. Hypertension only rarely required treatment discontinuation, and only two patients discontinued treatment due to hypokalemia (no hypokalemia-related deaths). Two patients in each arm died of cerebrovascular events, and 10 patients treated with ADT + AA + prednisone compared to 6 patients treated with ADT + placebo died of cardiac disorders.

STAMPEDE

STAMPEDE is a large multi-stage, multi-arm, RCT being conducted in the United Kingdom to assess the utility of novel therapeutic agents in conjunction with ADT. Currently being tested are AA, enzalutamide, zoledronic acid, docetaxol, celecoxib and radiotherapy (RT). The AA arm of the study was presented at ASCO as a late-breaking abstract. Inclusion criteria included men with locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer, including newly diagnosed with N1 or M1 disease, or any two of the following: stage T3/4, PSA ≥ 40 ng/mL, or Gleason score 8-10. Patients undergoing prior radical prostatectomy or RT were eligible if they had more than one of the following: PSA ≥ 4 ng/mL and PSADT < 6 months, PSA ≥ 20 ng/mL, N1, or M1 disease. Patients were then randomized 1:1 to standard of care (SOC; ADT for ≥2 years, n=957) vs SOC + AA (1000 mg) + prednisone 5 mg daily (n=960). Treatment with RT was mandated in patients with N0M0 disease, while strongly encouraged for N1M0 patients. Primary outcomes were OS and failure-free survival (FFS), where failure was defined as PSA failure, local failure, lymph node failure, distant metastases or prostate cancer death. Secondary outcome included toxicity and skeletal-related events (SREs). The study was powered to detect a 25% improvement in OS for the treatment group (requiring 267 control arm mortalities).

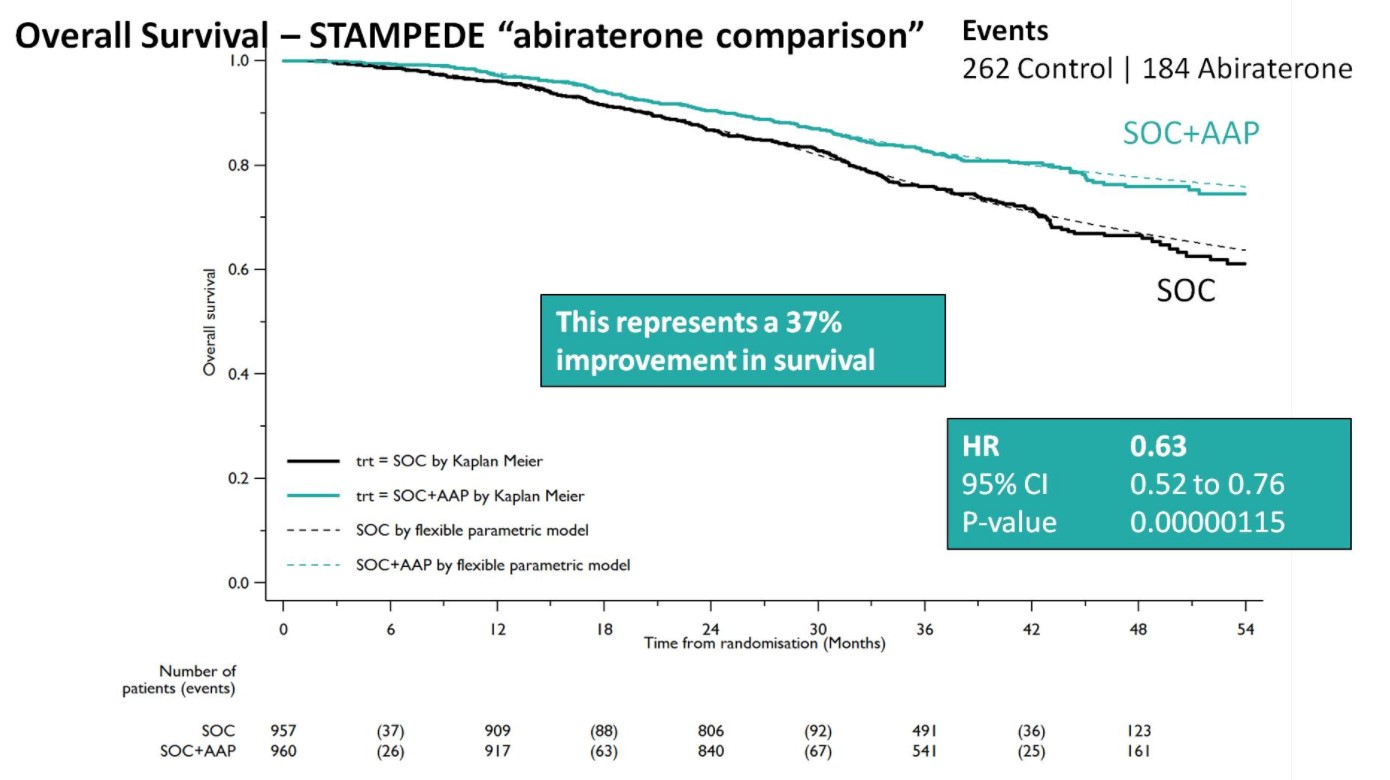

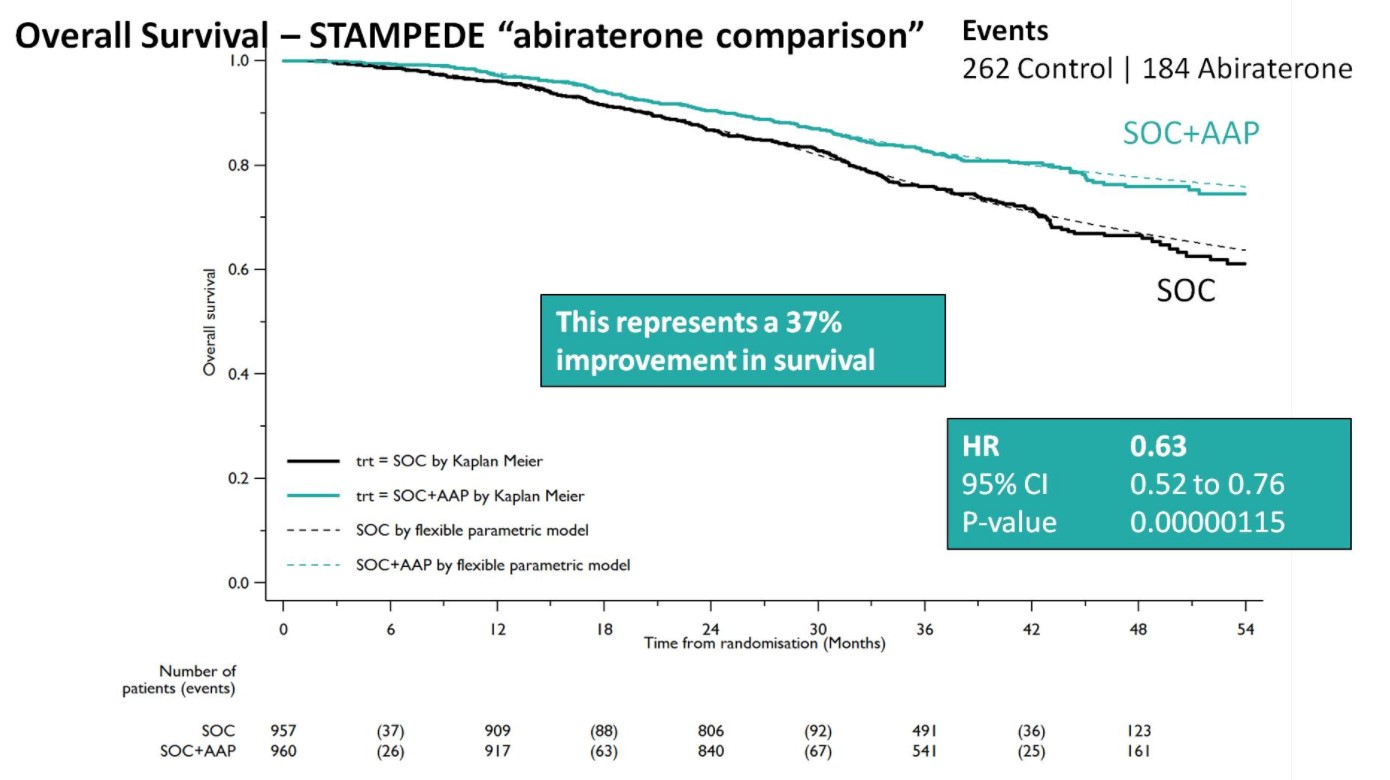

Both groups were balanced and patients were predominantly metastatic (52% M1, 20% N+M0, 28% N0M0), median was PSA 53 ng/mL, and 99% were treated with LHRH analogues. Over a median follow-up of 40 months, there were 262 control arm deaths, of which 82% were prostate cancer-related; there were 184 deaths in the SOC + AA + prednisone arm. There was a 37% relative improvement in overall survival (HR 0.63, 95%CI 0.52-0.76) favoring SOC + AA + prednisone.

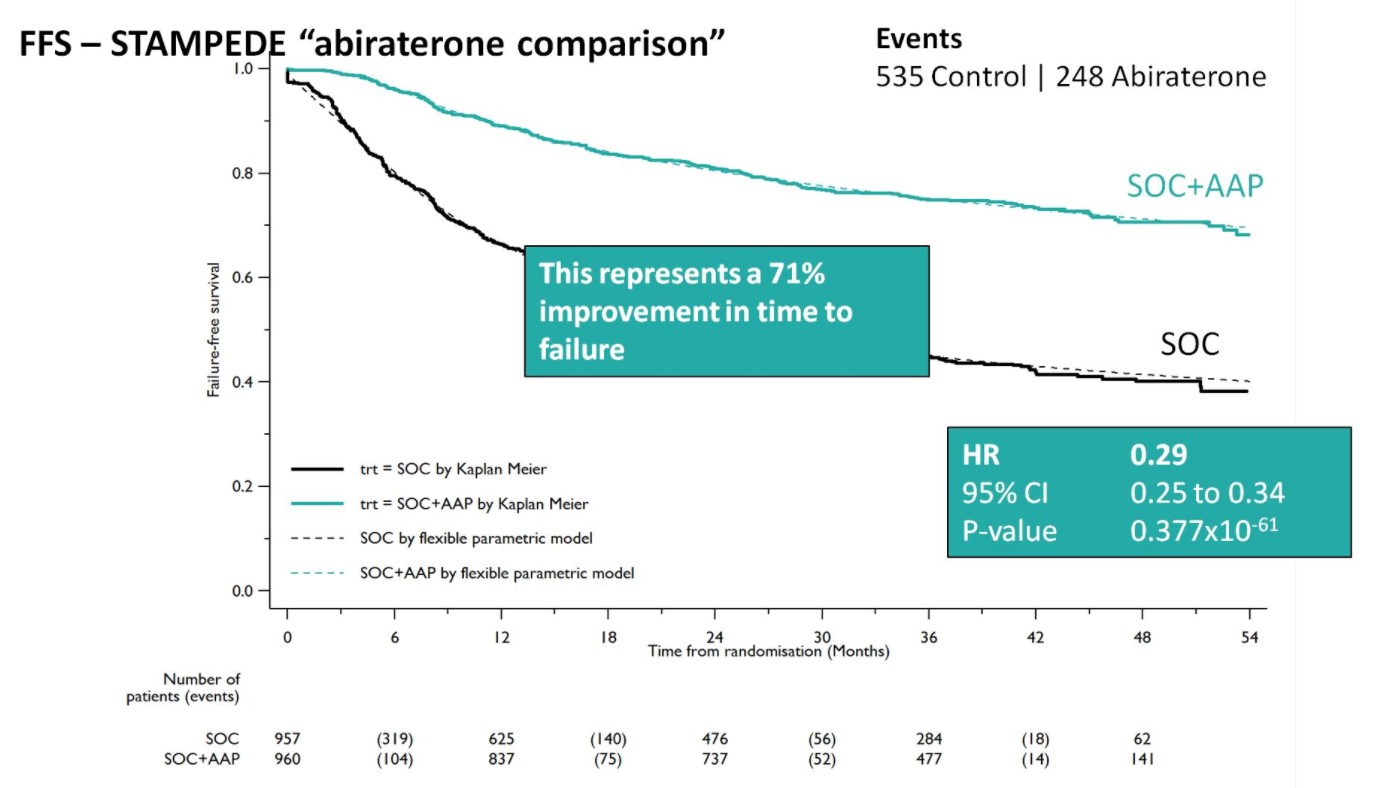

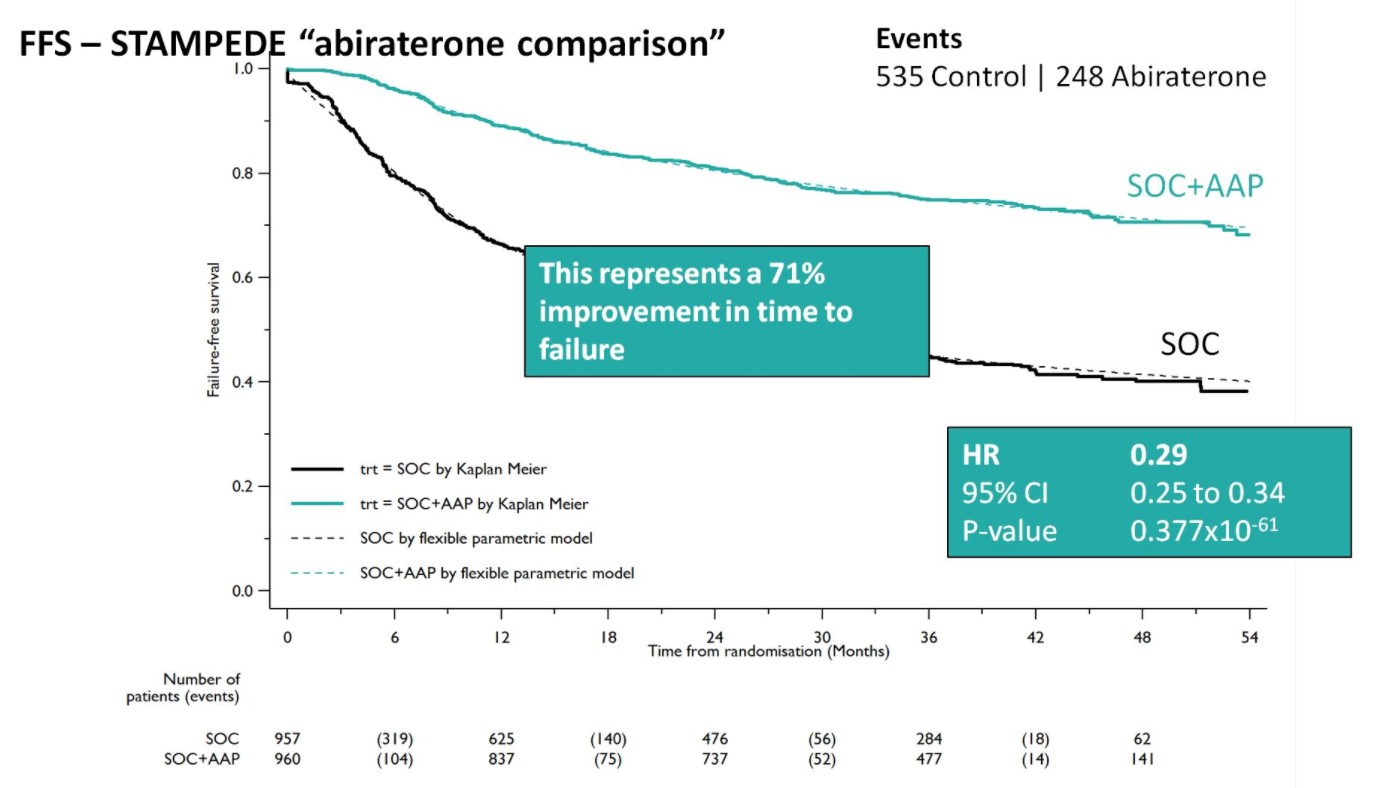

A Forrest plot split on stratification factors demonstrated no evidence of heterogeneity based on any of the factors, including M0/M1 status (p=0.37). Second, SOC+AA + prednisone demonstrated a 71% improvement in FFS (HR 0.29, 95%CI 0.25-0.34), with an early split in the KM curves.

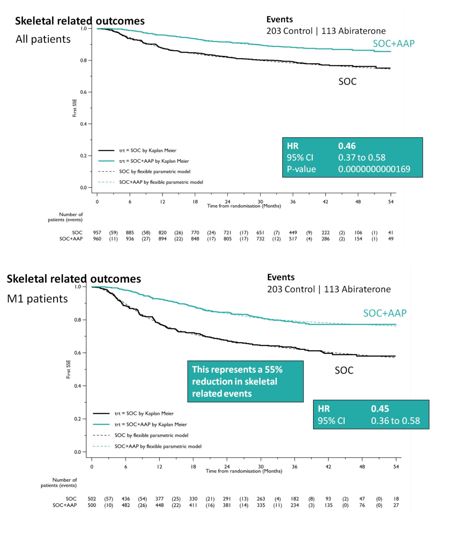

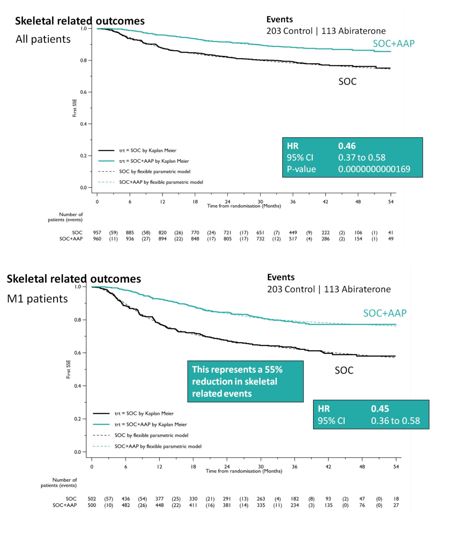

SOC + AA + prednisone also significantly decreased SREs among the entire cohort (HR 0.46, 95%CI 0.37-0.58), as well as specifically in the M1 cohort (HR 0.45, 95%CI 0.37-0.58). This resulted in a 55% reduction in SREs in the M1 subset analysis.

When looking at treatment progression, 89% of the SOC arm went on to next line of therapy, whereas 79% of the SOC + AA + prednisone arm received additional therapy, most commonly docetaxel. As expected, the rate of Grade 3-5 adverse events was higher in the SOC + AA prednisone arm (47% vs. 33%), and were primarily cardiovascular (HTN, MI, cardiac dysrhythmias) or hepatic (transaminitis) in nature.

REACTION, INTERPRETATION & FUTURE DIRECTIONS

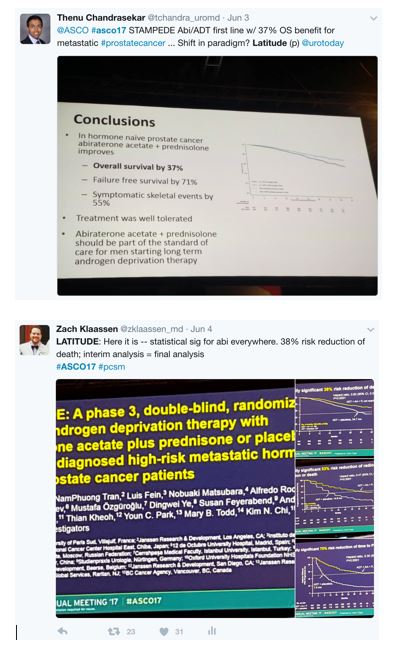

As has become the norm during academic conferences, there was significant buzz on Twitter over the course of the two days these results were presented:

This also included the New England Journal of Medicine immediately tweeting after the presentations that LATITUDE and STAMPEDE were published instantaneously:

Furthermore, immediately following Dr. Fizazi’s presentation of LATITUDE, Dr. Eric Small from @UCSF presented a discussion of LATITUDE. A number of important points were raised. First, although this was a well-designed, placebo controlled, randomized phase III study, early unblinding (although appropriate) resulting in an HR of 0.62 for OS is based on only 50% of the targeted total deaths. Making conclusions based on interim analyses must be made with caution. However, with every endpoint reaching statistical significance and conditional probability modeling, if the study had remained blinded, the probability of reaching the same conclusions is high. Second, since twice as many patients in the ADT + placebo arm received life-prolonging therapy than compared to the ADT + AA + placebo arm, the benefit of AA is not explained by more secondary life-prolonging therapy, strengthening the cause for AA + ADT.

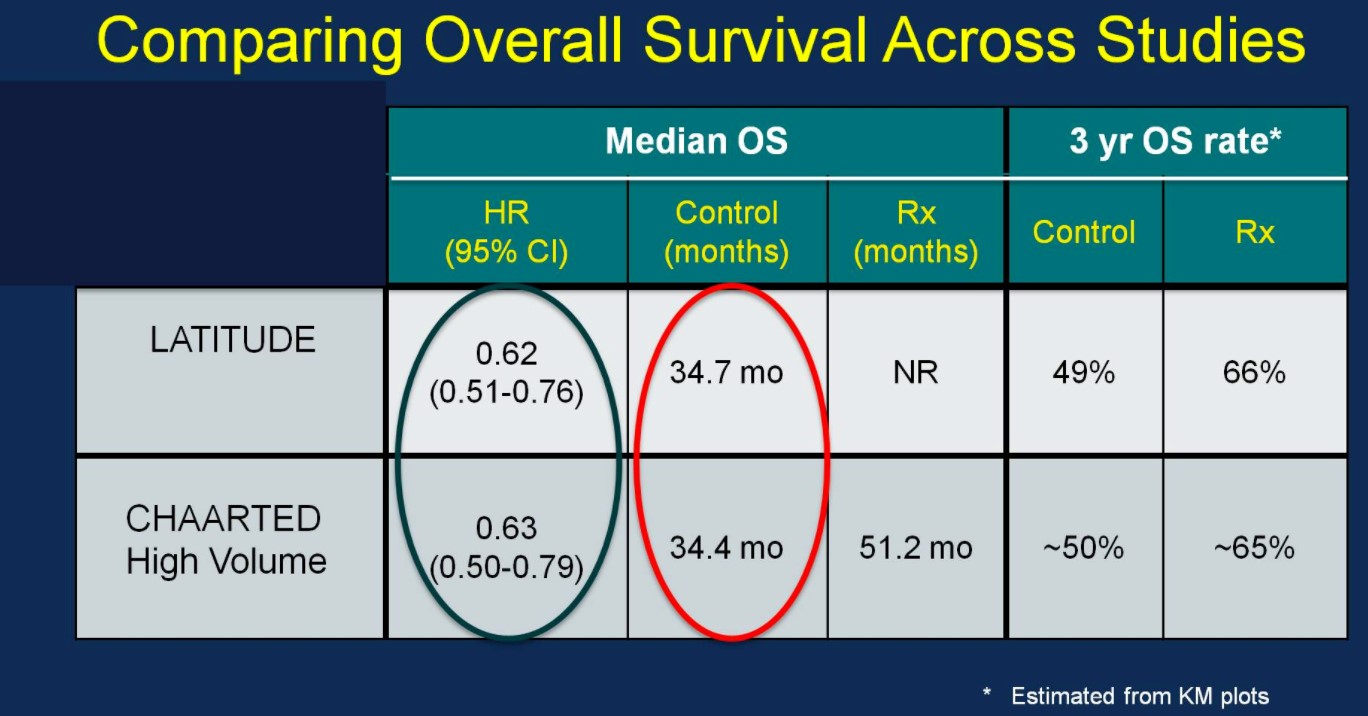

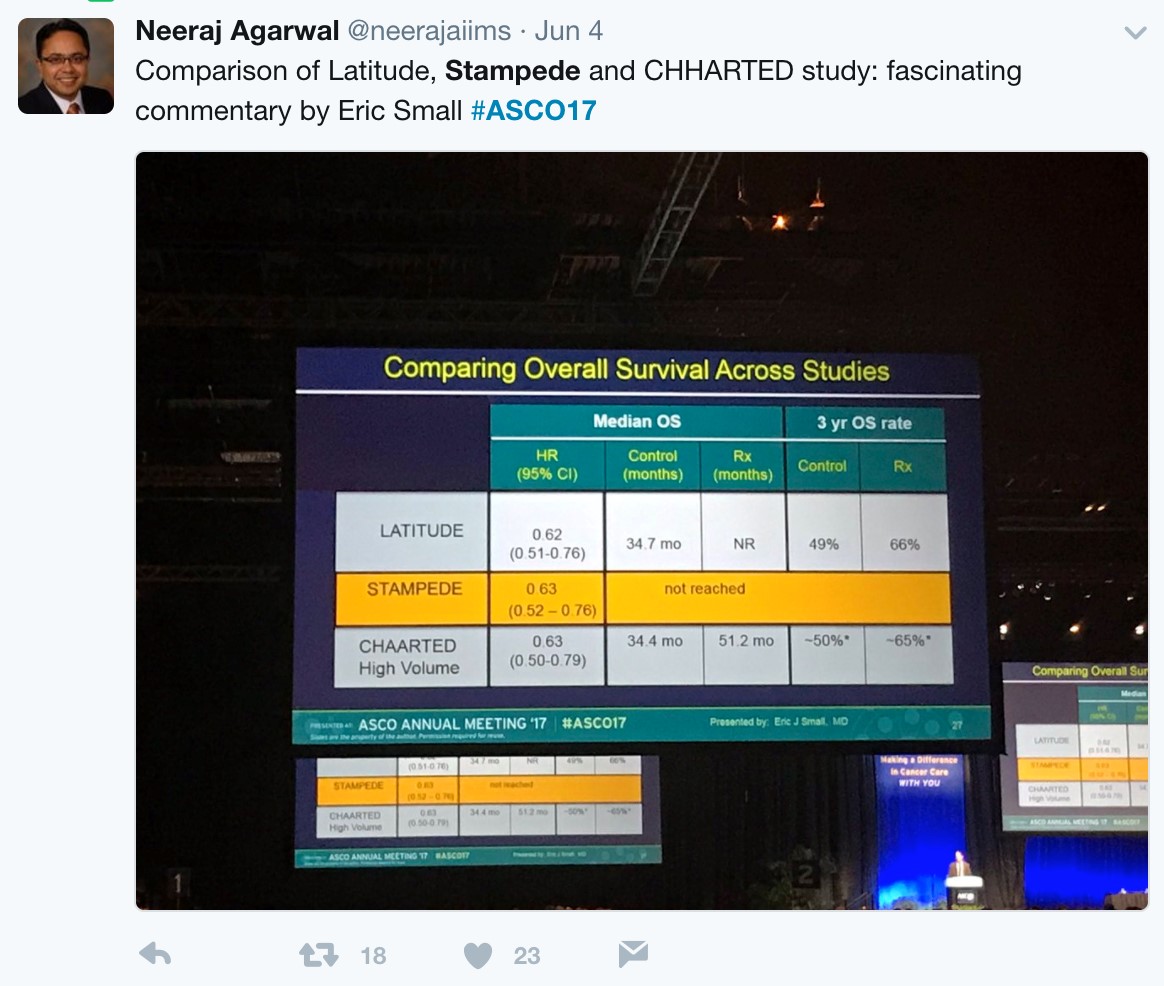

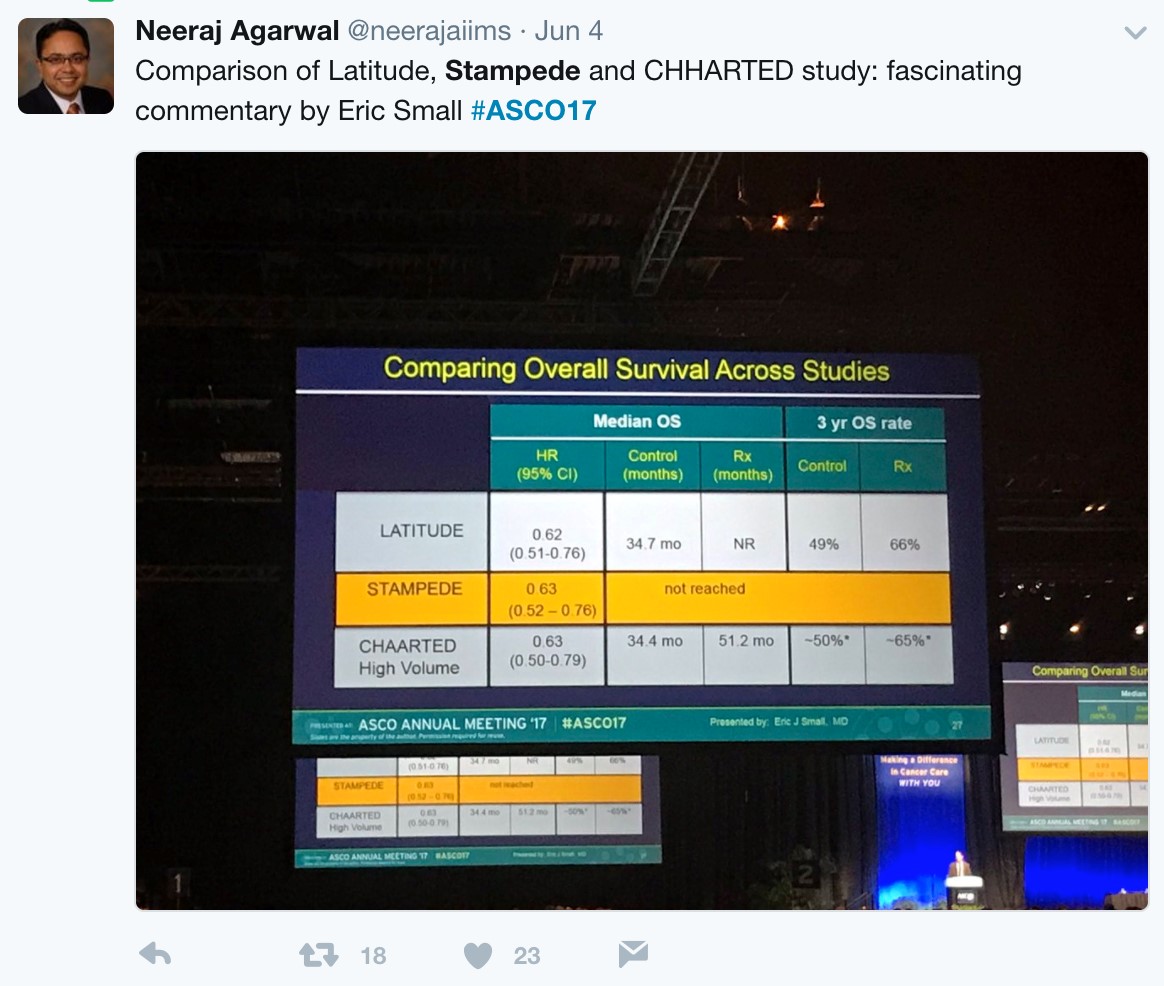

Perhaps the most interesting and pertinent clinical comparison is assessing outcomes of the LATITUDE and CHAARTED (high-volume disease) treatment arms (AA vs docetaxel). With similar median OS outcomes between the ADT control arms of the two trials (suggesting similar populations), the HRs for OS based on treatment are nearly identical:

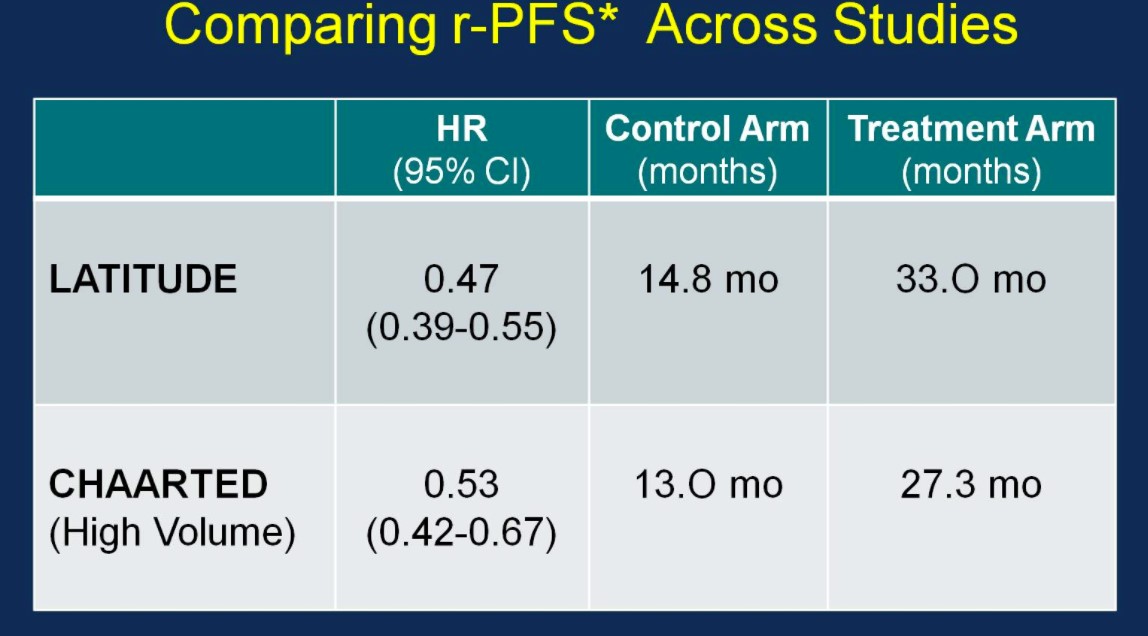

Similarly, the rPFS outcomes were comparable between the two trials:

With nearly identical OS and rPFS outcomes for men receiving ADT + AA or ADT + docetaxel, the question becomes whether the impact of adding AA to ADT is volume or risk dependent. Results from the STAMPEDE trial would suggest remarkably similar outcomes support the use of AA + ADT in patients with less burden of disease. Arguably the most important slide of the meeting was captured and tweeting by Dr. Agarwal (@neerajaiims):

Dr. Small eloquently summarized future directions into two groups. Unanswered questions regarding efficacy include: (i) Can a genomic classifier be used to select patients more likely to benefit from AA or docetaxel? (ii) Can AA be added in even earlier settings (with radiation? Increasing PSAs?) (iii) Should AA and docetaxel be combined or used sequentially? Additionally, there are also unanswered questions regarding AA resistance, including (i) Will the mechanisms of resistance to AA be the same when used in the non-mCRPC setting? (ii) Will androgen receptor amplification still be observed? (iii) Will there be an increased risk of treatment-associated small cell/neuroendocrine prostate cancer? (iv) Does adding chemotherapy or AA to ADT result in more aggressive disease at the time of resistance? (v) What is the optimal therapy for a patient who progresses on ADT + AA, compared to a patient who progresses on ADT + docetaxel? Given the avoidance of potential chemotherapy related side effects (ie. neutropenic complications) for an oral, long-term treatment, AA + ADT should be considered standard of care for untreated, high-risk metastatic prostate cancer.

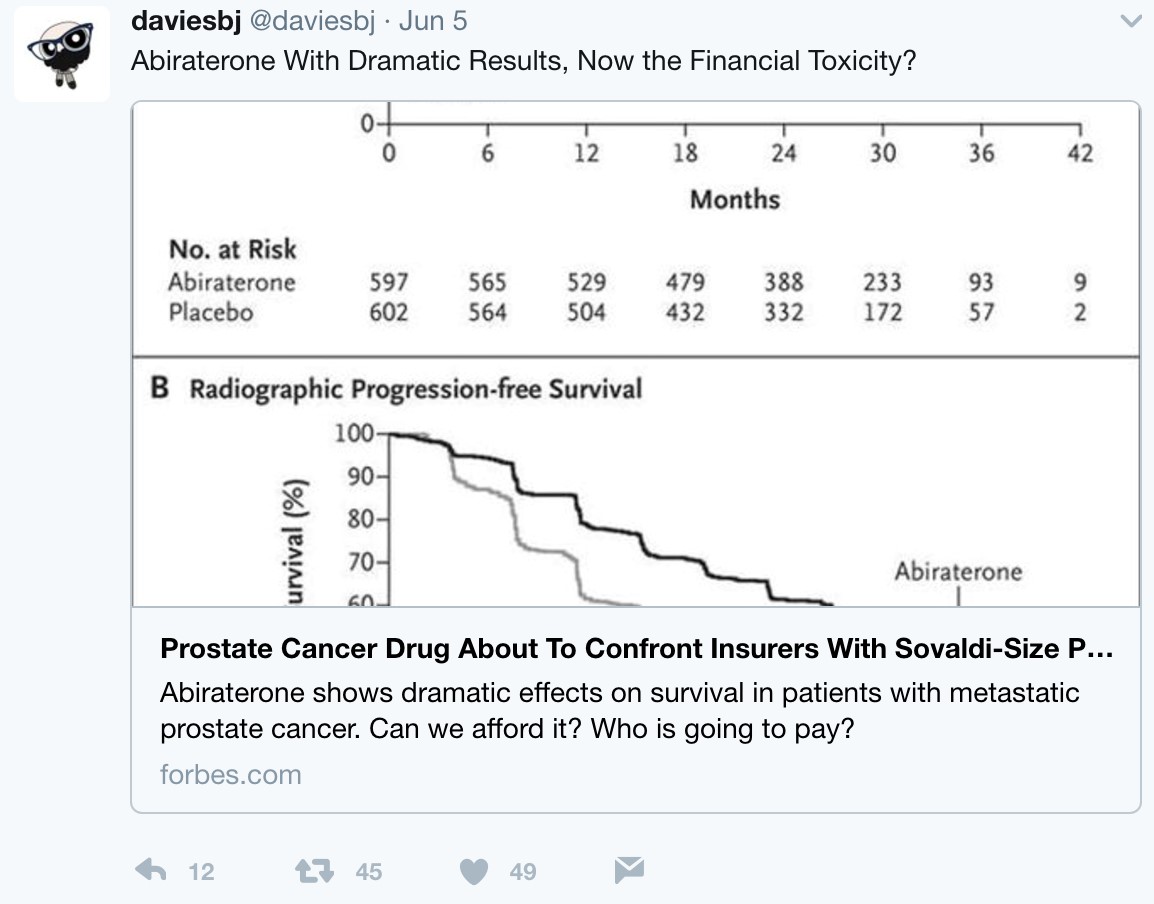

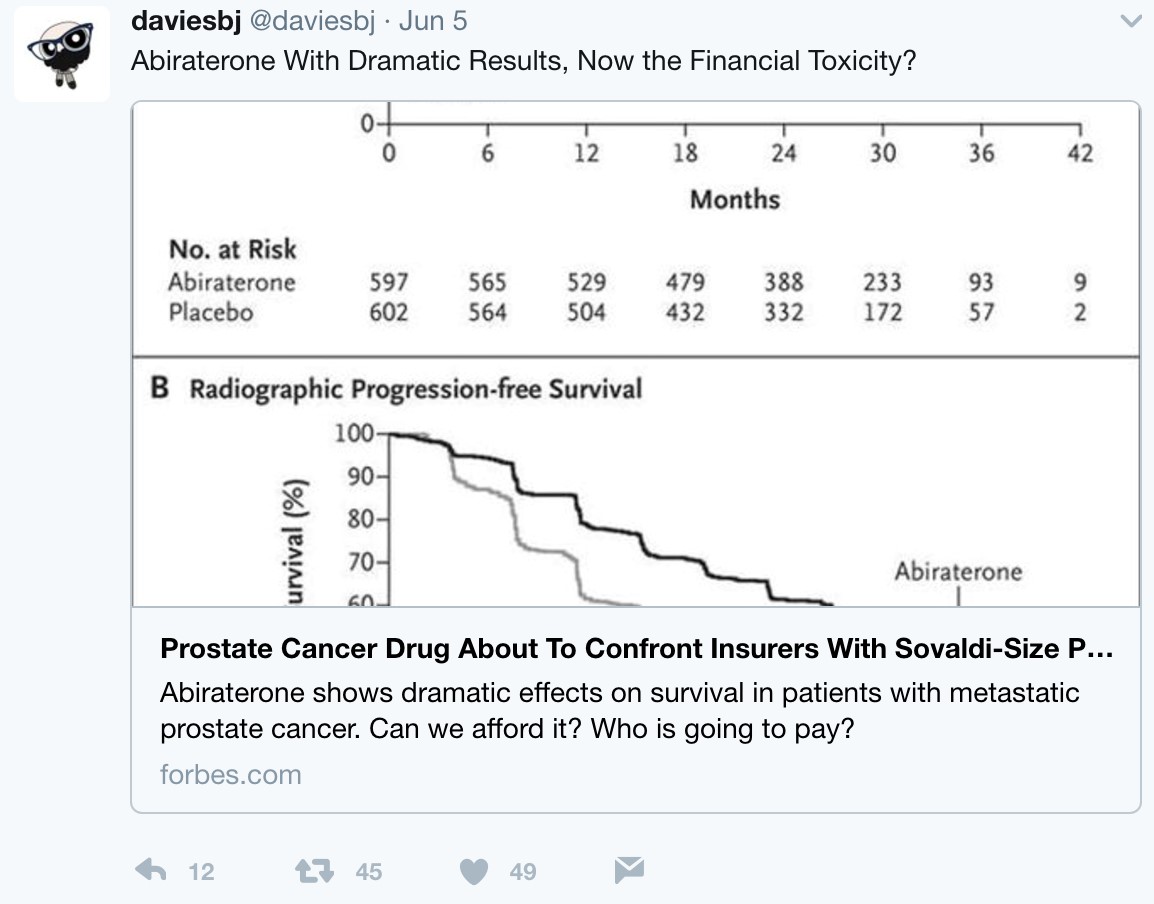

But what is the long-term economic landscape like when practice changing trials such as LATITUE and STAMPEDE suddenly thrust an expensive medication such as AA + prednisone directly to the forefront of hormone-naïve disease? Following these presentations, urologic oncologist, Twitter veteran, and Forbes correspondent Dr. Ben Davies (@daviesbj) wrote a provocative piece highlighting the potential ‘financial toxicity’ (particularly in the United States) that may result downstream of these trials:

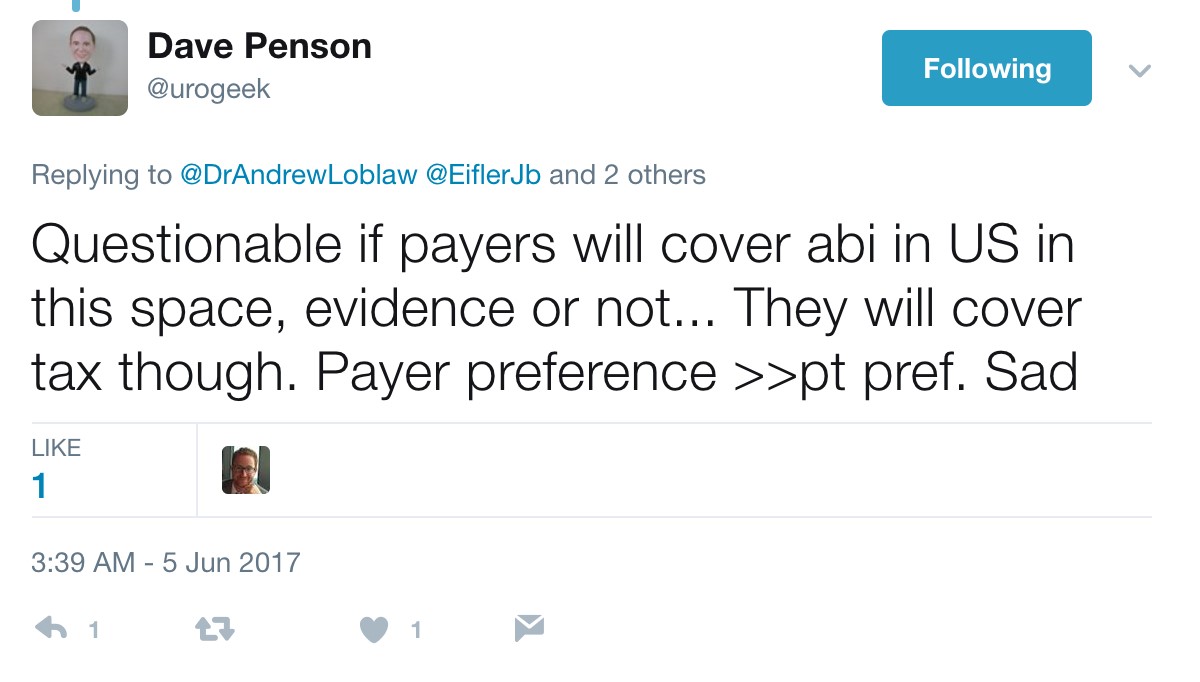

A conservative estimate is a wholesale cost of $115,000 per year per patient for AA + prednisone, resulting in a crude estimate of a $2.8 billion annual expenditure for the drug in the United States alone if used in the hormone-naïve setting, according to Dr. Davies. As Dr. Davies also points outs, although the patent for AA expired in 2016 and there are currently 13 applications to make generic AA, the patent for prednisone lasts until 2027, with $30 billion riding on the lawsuit. Dr. David Penson (@urogeek) succinctly summarized via Twitter:

Strictly academically speaking, LATITUDE and STAMPEDE, in addition to the docetaxel benefits of CHAARTED, have provided clinicians with exciting Level 1 evidence for improving patient care in the high-risk/metastatic setting. The investigators and more importantly the thousands of patients and families are to be thanked and congratulated for their perseverance, hard-work, and willingness to participate in these practice-changing clinical trials. It is our job as clinicians to continue advocating the best treatment for our patients, whether this be through economic barriers in the United States, or access to appropriate care on a global scale.

Zach Klaassen, MD

Urologic Oncology Fellow

University of Toronto/Princess Margaret Cancer Centre

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

@zklaassen_md