Discussion

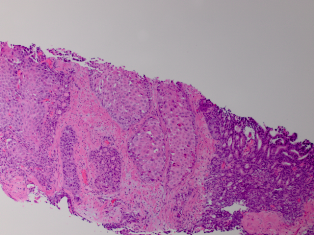

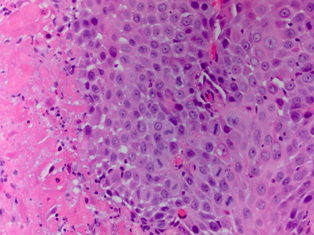

Unlike global testicular infarction, segmental testicular infarction (STI) is an uncommon testicular condition resulting from partial ischemia of the testis. STI commonly affects males between the second and fourth decades of life.1 However, several cases of STI in children have been reported.[1-3]

STI usually presents with acute scrotal pain and may resemble orchido-epididymitis or torsion of the spermatic cord. The condition can, however, present without pain. Sometimes swelling of the testis is present. In early stages palpation of the testis is normal, however, in more advanced cases an indurated testicular mass can be detected.[4]

Partial ischaemia of the testis is thought to be secondary to venous thrombosis, for which various local and systemic disorders have been reported as causal factors. Such factors include sickle cell anemia, polycythemia, vasculitis, iatrogenic vascular injury, trauma, arterial intimal fibroplasia and previous epididymo orchitis.[5-8] Another possible mechanism reported only recently by Adachi et al. is cholesterol embolism-associated STI.[8] However, the majority of cases have been reported as idiopathic.[5]

In this case the patient was initially treated for acute epididymitis with antibiotics by his general physician. Although it may be possible that this patient developed an STI secondary to epididymitis, our patient had no clinical, laboratory, or echographical signs for this condition. In addition, there was no history of systemic disease or genital trauma. In this case therefore, the STI could be considered idiopathic.

The majority of cases of STI reported in the literature underwent a (partial) orchiectomy because of the suspicion of malignancy or the need for histology for definitive diagnosis.[5] However, a conservative approach to STI is possible and safe if the diagnosis is reached with a high degree of certainty.[9,10] In this patient we had not reached a high degree of certainty. The age of the patient, the acute onset of pain and negative tumor markers were suggestive of a non malignant condition. However, acute scrotal symptoms may occur in patients with testicular tumors.[11] On the other hand, weight loss of 11 kilograms and the firm mass palpable within the parenchyma were more suggestive of a possible malignancy.

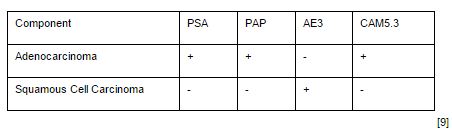

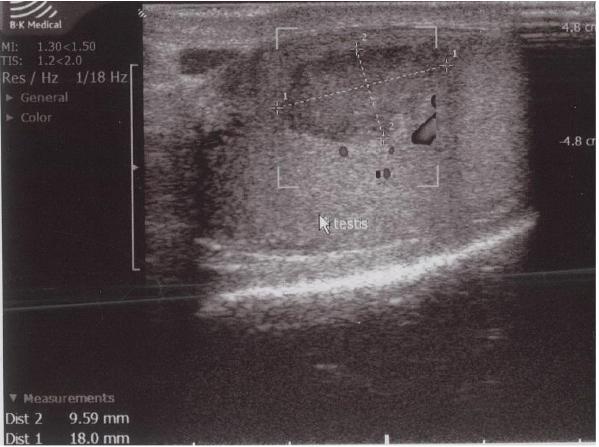

Although ultrasound is the first choice diagnostic tool in evaluating scrotal pain, distinguishing the hypoechogenic lesion from a testicular tumor on ultrasound was difficult in this case. This difficulty in distinguishing between testicular infarction and testicular tumor, especially in small sized lesions, is also reported by other authors.[4,12] STI in adults usually is wedge shaped on ultrasound as is demonstrated by the study of Fernández-Pérez et al.[13] In our patient, the lesion was oval shaped. Several studies have also reported a round morphology. [5,6,13]

Color Doppler ultrasound showed an avascular central zone with several peri-lesional spots with low colour signals. However, on Color Doppler ultrasound it can be difficult to detect increased blood flow in tumors less than 2 cm in size.[14] In any case, the presence of hypervascularity is not specific for the diagnosis of malignancy, because of the frequent hypovascular pattern of testicular tumors.[15] Therefore, an intratesticular tumor could not be excluded in our patient despite the absence of blood flow in the center of the hypoechogenic lesion.

When a discrepancy between clinical and ultrasonographic findings exists, MRI with contrast may provide additional information over ultrasound, occasionally showing a well-circumscribed hypo-intense area with an enhanced rim, indicating an STI.[13] Nevertheless, definite exclusion of a testicular tumor is not always possible because MRI may demonstrate different findings for different stages of infarction, showing lesions that are lacking the typical features previously mentioned.[16] The use of contrast enhanced ultrasound in the diagnosis of STI seems promising but requires further investigation.[6]

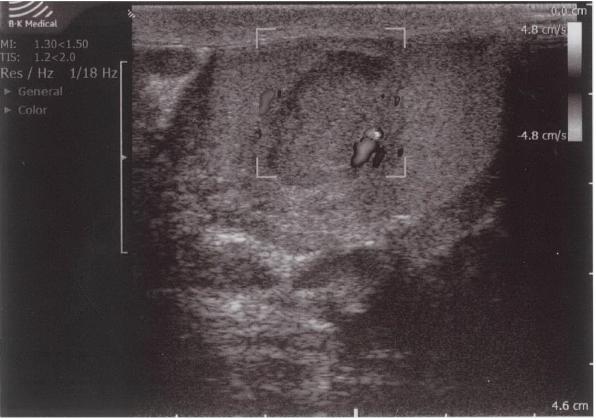

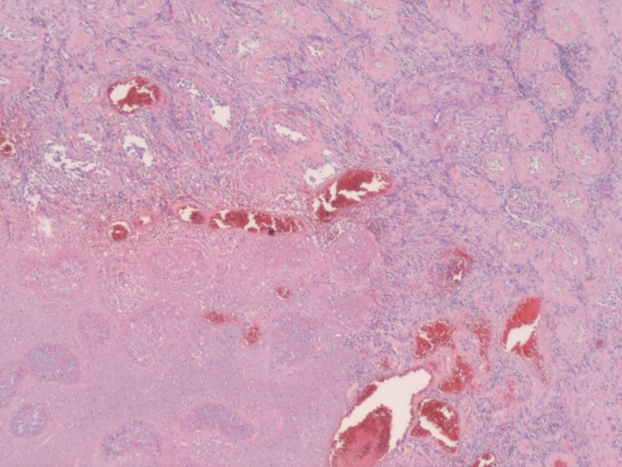

When STI cannot be diagnosed based on the clinical picture and radiologic findings, histological examination is necessary. In most studies STI is histologically confirmed following radical or partial orchiectomy.[4,8,16,19,20] However, in certain cases sparing of the testis is desired and a less invasive way for obtaining a histological confirmation is needed. Perioperative frozen section examination has proven to be accurate for distinguishing benign from malignant lesions, allowing the testis to be spared. In addition, there is no evidence that oncological safety is impaired with this technique.[17] Several studies have showed the feasibility of this method of confirming histology.[1,12,21] In the case of nonpalpable or small hypoechogenic lesions, intraoperative ultrasound guided needle localization with microsurgical exploration has proven to be a safe and effective approach for microsurgical removal of the lesion and obtaining histology. This allows maximal preservation of the testicular parenchyma and its vasculature.[22,23] In this case frozen section examination was not performed, because the patient did not want to take any risk of the tumor being missed on the frozen section. In addition, because of his age our patient was not troubled by the fact of having one testis for the rest of his life.

As previously mentioned, conservative management has been proven to be possible and safe in highly selected patients where a diagnosis of STI has been made with a high degree of certainty. According to the literature, patients clinically supected to have for STI, with negative tumor markers and Doppler ultrasound and contrast enhanced MRI indicating a STI, are suitable for conservative management with scrotal ultrasound follow-up. Several studies report the development of the ultrasound appearance of STI during follow up ranging from one day to five years.[6,7,9,10] In these studies, follow-up ultrasound demonstrated no progression, or a gradual reduction in size of the lesion, with reflectivity and vascularity essentially unchanged or diminished. This could differentiate STI from a testicular tumor.

In conclusion, differential diagnosis between STI and testicular maligancy remains difficult. STI is therefore mostly detected after (partial) orchiectomy. Some features may suggest this benign condition; a hypovascular wedge-shaped lesion, in patients with normal tumor markers. In highly selected patients, diagnosis with a high degree of certainty allows conservative treatment with strict follow-up ultrasound. However, if the clinical picture and radiologic imaging are inconclusive or unclear, histologic confirmation cannot be avoided. In that case explorative surgery together with (microsurgical) frozen section examination should be performed, especially in patients in whom sparing of the testis is desired. In the future, further studies are needed to better diagnose this benign condition.

References

1) Kim HK, Goske MJ, Bove KE, Minovich E. Segmental testicular infarction in a young man simulating a testicular tumor. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:400–402

2) Fukuda S, Takahashi T, Kumori K, Takahashi Y, Yasuda K, Kasai T, Yamaguchi S. Idiopathic testicular infarction in a boy initially suspected to have acute epididymo-orchitis associated with mycoplasma infection and Henoch-Schönlein purpura. J Pediatr Urol. 2009;5:68-71

3) Barber TD, Al-Omar O, Poulik J, McLorie GA. Testicular infarction in a 12-year-old boy with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Urology 2006;67:846.e9-10

4) Ruibal M, Quintana JL, Fernández G, Zungri E. Segmental testicular infarction.

J Urol.2003;170:187-188.

5) Gianfrilli D, Isidori AM, Lenzi A. Segmental testicular ischaemia: presentation, management and follow-up. Int J Androl. 2009;32:524-31

6) Bertolotto M, Derchi LE, Sidhu PS, Serafini G, Valentino M, Grenier N, Cova MA. Acute segmental testicular infarction at contrast-enhanced ultrasound: early features and changes during follow-up. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:834-41

7) Bilagi P, Sriprasad S, Clarke JL, Sellars ME, Muir GH, Sidhu PS. Clinical and ultrasound features of segmental testicular infarction: six-year experience from a single centre. Eur Urol. 2007;17:2810-2818

8) Adachi S, Tsutahara K, Kinoshita T, Hatano K, Kinouchi T, Kobayashi M, Inoue H, Takada T, Hara T, Yamaguchi S. Segmental testicular infarction due to cholesterol embolism: not the first case, but the first report. Pathol Int. 2008;58:745-8

9) Madaan S, Joniau S, Klockaerts K, DeWever L, Lerut E, Oyen R, Van Poppel H. Segmental testicular infarction: conservative management is feasible and safe. Eur Urol. 2008;53:441-445

10) Madaan S, Joniau S, Klockaerts K, DeWever L, Lerut E, Oyen R, Van Poppel H. Segmental testicular infarction. Conservative management is feasible and safe: part 2. Eur Urol. 2008;53:656-658

11) Guthrie JA, Fowler RC. Ultrasound diagnosis of testicular tumours presenting as epididymal disease. Clin Radiol. 1992;46:397-400

12) Calcagno C, Gastaldi F. Segmental testicular infarction following herniorrhaphy and varicocelectomy. Urol Int. 2007;79:273-275

13) Fernández-Pérez GC, Tardáguila FM, Velasco M, Rivas C, Dos Santos J, Cambronero J, Trinidad C, San Miguel P. Radiologic findings of segmental testicular infarction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1587-1593

14) Venugopal S, Schoeman D, Damola A, Hamid B, Powell C. Acute scrotal pain with a twist. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:24-26

15) Horstman WG, Melson GL, Middleton WD, Andriole GL. Testicular tumors: findings with color Doppler US. Radiology 1992;185:733-737

16) Kodama K, Yotsuyanagi S, Fuse H, Hirano S, Kitagawa K, Masuda S. Magnetic resonance imaging to diagnose segmental testicular infarction. J Urol. 2000;163:910–911

17) Kirkham AP, Kumar P, Minhas S, Freeman AA, Ralph DJ, Muneer A, Allen C. Targeted testicular excision biopsy: when and how should we try to avoid radical orchiectomy? Clinic Radiol. 2009;64:1158-1165

18) Sharma SB, Gupta V. Segmental testicular infarction. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72:81-82

19) Secil M, Kocyigit A, Aslan G, Kefi A, Ozdemir I, Tuna B, Yorukoglu K. Segmental testicular infarction as a complication of varicocelectomy: sonographic findings. J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34:143-145

20) Flanagan JJ, Fowler RC. Testicular infarction mimicking tumour on scrotal ultrasound – a potential pitfall. Clin Radiol. 1995;50:49-50

21) Hidalgo J, Rodríguez A, Canalias J, Muntané MJ, Huerta MV, Carrasco N, Vesa J. Segmental testicular infarction vs testicular tumour: the usefulness of the excisional frozen biopsy. Arch Esp Urol. 2008;61:92-93

22) Hopps CV, Goldstein M. Ultrasound guided needle localization and microsurgical exploration for incidental nonpalpable testicular tumors. J Urol. 2002;168:1084-1087

23) Kravets FG, Cohen HL, Sheynkin Y, Sukkarieh T. Intraoperative sonographically guided needle localization of nonpalpable testicular tumors. AJM Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:141-143