The NICE (National Institute For Health And Care Excellence) “Renal and ureteric stones: assessment and management” guideline NG118 was published on-line on Tuesday 8th January 2019 and appeared on the BJUI website on Friday 18th January.

NICE guidelines are based on the best available evidence for the treatment of the specific clinical condition evaluated (i.e. from randomised controlled trials) and aim to provide recommendations that will improve the quality of healthcare within the NHS. As such, the need for a particular guideline is determined by NHS England, and NICE commissions the NGC produce it. The renal and ureteric stone guidelines are comprised a series of evidence reports, each based on the PICO system for a systematic review, covering the breadth of stone management in patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic renal or ureteric stones from initial diagnosis and pain management, through the much debated subject of medical expulsive therapy, to a comprehensive assessment of the surgical treatment of stone disease, including pre- and post- treatment stenting. Follow up imaging, dietary intervention and metabolic investigations have also been reviewed and analysed in detail. These reports are summarised in what is referred to as “The NICE Guideline”, and which is published in the BJUI itself in the February issue (Volume 123, Issue 2, February 2019). The guideline uses the term “offer” to indicate a strong recommendation with the alternative “consider” to indicate a less robust evidence base, with both terms chosen to highlight the need for patient-centred discussion and shared decision making. Indeed, the preface to The Guideline points out the importance of clinical judgment, and that “the individual needs, preferences and values” of patients should be taken into account in decision making, emphasising that “the guideline does not override the responsibility to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual”.

We have written these blogs to highlight the individual reports, which can be downloaded from NICE at www.nice.org.uk, and to stimulate some thoughts and comments about their implications for the management of stone patients in the UK and internationally.

Daron Smith and Jonathan Glass

Institute of Urology, UCH and Guys and St Thomas’ Hospitals

London, January 15th 2019

Daron Smith Commentary

Considering the patient journey to begin with acute ureteric colic, the first recommendation is that a low-dose non-contrast CT should be performed within 24 hours of presentation (unless a child or pregnant) [Evidence Review B, a 73 page document analysing 5224 screened articles, of which 13 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. Their pain management should be with NSAIDs as first line pain relief, i.v. paracetamol as second line and opioids as third line, but antispasmodics should not be used [Evidence Review E, a 227 page document for which 1685 articles were screened, of which 38 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. Somewhat contentiously for UK practice, given the SUSPEND findings, is that alpha blockers should be considered for patients with distal ureteric stones less than 10 mm [Evidence Review D, a 424 page document for which 1351 articles were screened, of which 71 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review].

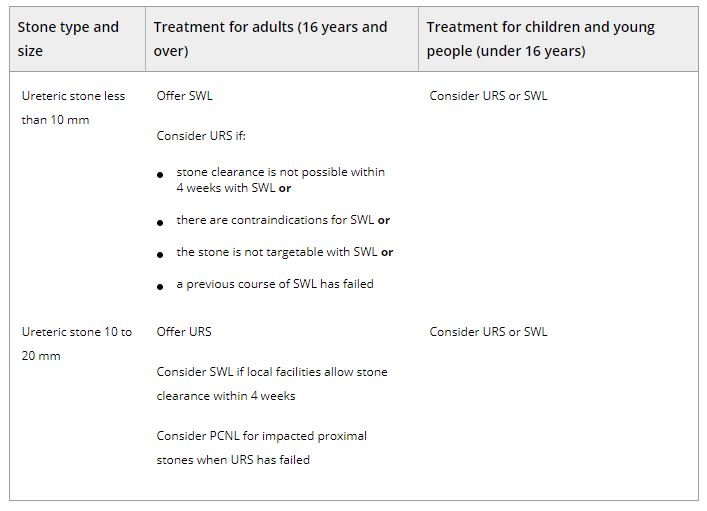

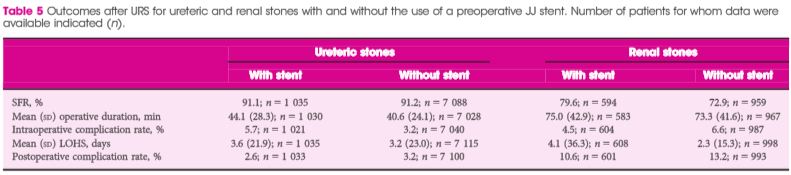

As far as stone interventions are concerned, observation was deemed to be reasonable for asymptomatic stones, especially if less than 5mm, that ESWL should be offered for renal stones less than 10mm and PCNL offered for those greater than 20mm with those in between having all options to be considered. Ureteric stones less than 10mm should be offered ESWL (unless unlikely to be cleared within 4 weeks, or contraindicated, or previously failed) whereas ureteric stones larger than 10mm should be offered URS. These conclusions were drawn from 2459 articles of which 66 were of sufficient quality to be included and summarised [Evidence Review F, a 369 page document]. Perhaps the most important aspect for change in practice relate to the use of stents (both before and after treatment) and the timing of definitive intervention (i.e. without a prior temporising JJ stent). Specifically, the guidance recommends patients with uncontrolled pain, or where the stone is deemed unlikely to pass spontaneously, should have definitive treatment within 48 hours [Evidence Review G, a 39 page document based on 3234 screened articles of which 3 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. Stents should not be inserted before ESWL for either renal or ureteric stones [Evidence Review H, a78 page document for which 1630 articles were screened, 7 being sufficiently high quality to be included in the review]. Patients who undergo URS for stones less than 20mm should not have a post-operative stent placed as a matter of routine [Evidence Review I, a 107 page document derived from 1630 screened articles of which 17 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. Clearly individual circumstances (ureteric trauma, need for second phase procedure, infection, risk of renal insufficiency) apply to this decision. Given that currently a URS is reimbursed at £2,172, and stent removal as £1,018, perhaps it is time that the treatment episode is remunerated as a combined £3,190, thereby encouraging stent-less procedures instead of stented ones…

Once the treatment is complete, the optimum frequency of follow-up imaging was assessed, comparing monitoring visits less than 6 monthly against 6 monthly and with rapid access/review on request, a strategy that includes no follow up at all for asymptomatic patients [presented in the 29 page Evidence Review J, in which 2385 articles were screened, but none of which were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. No specific recommendations could therefore be made, other than the need to specifically evaluate the effectiveness of 6 monthly reviews for three years in future research. Of course, if preventative management were more effective, then imaging review would become less important… The guidelines have also reviewed the non-surgical options to avoid stone recurrence [summarised in Evidence Review K – “prevention of recurrence” – a 141 page document in which 3187 articles were screened, of which 19 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review and Evidence Review C, an 81 page document in which 1785 articles were screened, of which 10 were of sufficient quality to be included in the review]. These advised a fluid intake of 2.5 to 3 litres of water per day (with added lemon juice) and that dietary sodium intake should be restricted but calcium intake should not. As far as medical therapy is concerned, potassium citrate and thiazide diuretics should be considered in patients with calcium oxalate stones and hypercalciuria respectively.

In the final aspect of the pathway for stone patients, the clinical and cost effectiveness of metabolic investigations including stone analysis, blood and urine tests (serum calcium and uric acid levels, and urine volume, pH, calcium, oxalate, citrate, sodium, uric acid and cystine) were compared to the outcomes achieved with no metabolic testing following treatment as appropriate for any recurrent stones. Outcomes sought included stone recurrence and need for any intervention, the nature of any metabolic abnormality detected, Quality of life and Adverse events related to the tests or treatment [reported in the 36 page Evidence Review A, in which 933 articles were screened, but which none were of sufficient quality to be reviewed]. A formal research study to evaluate the clinical and cost effectiveness of a full metabolic assessment compared with standard advice alone in people with recurrent calcium oxalate stones was recommended. Following comments in the review process, the guidelines have recommendation that serum calcium should be checked, and biochemical stone analysis considered.

In addition to these individual topic reports, a 49 page evidence review summaries the research methodology and provides an extensive glossary of terms, and a 73 page “Costing analysis of surgical treatments” provides the information regarding the cost effectiveness of the treatments, such as the estimates that 1000 URS procedures and follow up would cost £3,328,895 compared with £961,376 for 1000 ESWL treatments and follow up.

In conclusion, the NICE Guideline Renal and ureteric stones: assessment and management (NG118) is a 33 page summary of over 1700 pages of evidence and analysis. It is therefore an example of where the parts are very much greater than the sum: there is an enormous wealth of high quality data presented in the eleven Evidence Reviews, which are like individual handbooks of contemporary stone management, almost exclusively based on Level 1 Randomised Controlled Trial Evidence. At a time when Brexit dominates national and international news, this is a British Export that we can be proud of.

The real test, of course, will be in the delivery of these ideals, and it is likely that the goal of treating symptomatic patients with ureteric stones within 48 hours will be difficult to achieve. However, the guidance also points out that “local commissioners and providers of healthcare have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied when individual professionals and people using services wish to use it”. Along with the GIRFT report, the NICE guidelines are key drivers for change not just in the way that stone patients are managed by their urologist, but in the way that they are treated by the system. Who does not want to be able to treat a patient in pain, with a definitive intervention (be it ESWL or URS) within 48 hours, and without the need for a stent for either the patient or Urologist to worry about. That is the goal that these guidelines have set us; achieving that would be something that Endourologists can be very proud of, and our patients will be extremely grateful for. Are we up for the challenge?

DS

London, January 2019

Jonathan Glass Commentary

The NICE Stone Guidelines – clarification or confusion?

‘This guideline covers assessing and managing renal and ureteric stones.

It aims to improve the detection, clearance and prevention of stones, so reducing

pain and anxiety, and improving quality of life’.

This is the opening paragraph of the recently produced NICE guidelines on the management of urinary tract stones. The guidelines have been produced in the context of existing guidelines produced by the European Association of Urology and the American Urological Association pre-existing, and one hoped that these guidelines would add something for the treatment of stone disease in the UK to justify the expenditure spent producing them. I write these comments in full recognition of the terms of reference to which NICE adheres in producing a set of guidelines.

I, with other members of the committee of the Section of Endourology of BAUS wrote a response to the draft guidelines and we are delighted that the committee has changed some aspects of the published guidelines as a result of our (and other contributions) to the consultation process. I must record however that what follows is a personal opinion, and not that of the committee.

These guidelines do refer to patients with a single stone. That of course immediately means that they have limited application to many of our patients who have multiple stones at first presentation.

The draft guidelines, which are in the public domain, stated ‘Do not use opioids’ in the treatment of ureteric colic. Although this has been changed to ‘Do not offer opioids to adults, children and young people with suspected renal colic unless both NSAIDs and intravenous paracetamol are contraindicated or have not been effective’ this still potentially leaves patient in severe pain for too long. Our first duty as doctors is to relieve pain. In my view, as a doctor caring for stone patients but also as an individual who has suffered ureteric colic, if opioids are needed, they should be given in a timely manner.

The recommendations on medical expulsive therapy are unusual at best and arguably a little bizarre and confusing to the British urologist. There is good evidence from a large UK study – the SUSPEND trial – that alpha blockers have little role to play in improving stone passage. This is the best level 1 evidence in the use of alpha blockers in stone disease. The study was sponsored by the NIHR and as such was truly independent, was statistically robust, and randomised. A representation was made to the guidelines committee by the Aberdeen group that published the study following distribution of the draft guidelines pointing out the robust nature of their study and the less than robust nature of the studies that made up the meta-analysis from which the guideline was derived. I would suggest that this guideline puts British urologists in a situation of huge uncertainty about how we advise our patients in this regard. Do we tell our patients the best evidence shows one course of action – not to use alpha blockers, but the NICE guidelines suggest another path? (I am pleased however that the administration of nifedipine, the use of which appeared in the draft guidelines, was removed from the final document).

The recommendation about pre-stenting children with staghorn stones prior to lithotripsy is arguably an historical perspective. Children with staghorn stones should be considered for primary percutaneous surgery. The recommendation in the guideline possibly reflects review of papers in a field where treatments and approaches to care have changed considerably in the last 10 years. I recognise that robust level 1A evidence is lacking for these interventions. It could indeed be argued that a guideline stating ‘consider ESWL, ureteroscopy or PCNL’ for stones 10-20mm and for stones greater than 20mm or staghorn stones is of limited use. Complex patients require bespoke care individualised to the patient in front of the clinician, taking in to account the stone and all other factors with respect to the patient other than the stone.

Suggesting treatment within 48 hours of presentation of patients with ureteric stones including lithotripsy will put urologists under huge pressure. Patients could hold up these guidelines and demand care. Treatment within 48 hours is often unnecessary, has huge cost implications, may well be unachievable and could lead to excessive intervention. To introduce it successfully, given that most stones present to district general hospitals, would suggest that NICE is calling for a lithotripter in every DGH, and in so doing, suggests the death of the mobile lithotripsy service; alternatively it will require the rapid and streamlined transfer of patients to stone centres for intervention. Either way the cost implications of this are considerable. I am certainly an advocate for the clinically appropriate timely treatment of stone patients but producing guidelines that are possibly unrealistic and impossible to implement might be considered a missed opportunity.

The recommendation to not offer routine stenting to patients undergoing ureteroscopy is controversial. As clinicians we understand the symptoms caused by stents. We also know the risk of sepsis following any stone intervention, the pain from stones obstructing the ureter and the oedema generated by ureteroscopy in the unstented ureter. Sepsis from urological disease is life threatening. These guidelines allow the legal justification of leaving a ureter unstented post ureteroscopy. I don’t know and can’t always predict which patients are going to go septic post intervention. Stents in this scenario save lives but proving that with level 1A evidence is nigh on impossible. I have concerns that this recommendation is potentially harmful and may be dangerous. We accept that many patients have interventions and procedures that may appear unnecessary to protect the few where it is life saving. This is true of nasogastric tubes following major surgery, of patients having a radical prostatectomy, of the placement of the nephrostomy tube following percutaneous surgery. It is also true of stents after ureteroscopy.

The metabolic considerations are a little odd. Sending the stone for analysis is only something that should be considered in these guidelines, and yet recommendations are made – based on the stone analysis. Similarly, there are no recommendations for metabolic testing beyond taking a serum calcium, and yet treatments are recommended for patients with hypocitraturia or hypercalciuria with no suggestion when and in whom these conditions should be sought and diagnosed.

Is this an opportunity lost? Do these recommendations justify the considerable cost in time and money that NICE has put in? Are these guidelines potentially harmful – and will they result in the justification of stones not being sent for analysis, the inappropriate use of alpha blockers, obstructed infected kidneys after ureteroscopy and a serum creatinine never being sent.

I have a healthy scepticism for medicine by committee. The MDT discusses treatments for prostate cancer and makes recommendations without the patient being present. I am not sure this process has relieved me of my scepticism. ‘This guideline… aims to improve the detection, clearance and prevention of stones, so reducing pain and anxiety, and improving quality of life’. Read them, and decide for yourselves whether these aims have been met and the expense producing them justified.

JG

London, January 2019