Editorial: How long is long enough for pharmacological thromboprophylaxis in urology?

Each year, millions of patients who undergo urological surgery incur the risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, together referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE), and major bleeding. Because pharmacological prophylaxis decreases the risk of VTE, but increases the risk of bleeding, and because knowledge of the magnitude of these risks remains uncertain, both clinical practice and guideline recommendations vary widely [1]. One of the uncertainties is the recommended duration of pharmacological thromboprophylaxis.

In this issue of the BJUI, Naik et al. [2] provide an up‐to‐date review that summarises the articles that examined extended thromboprophylaxis in patients with cancer who underwent radical prostatectomy (RP), radical cystectomy (RC) or nephrectomy. The outcomes on which they focussed include risks of VTE, bleeding, renal failure and mortality – all potentially influenced by whether or not patients receive extended prophylaxis.

After screening >3500 articles, the authors included 18 studies, none of them randomised controlled trials (RCTs) [2]. They found that VTE risk is highest in open and robot‐assisted RC, and that, based on observational studies, extended thromboprophylaxis significantly reduces the risk of VTE relative to shorter duration prophylaxis. Evidence suggested that robot‐assisted RP, as well as both open and robot‐assisted partial and radical nephrectomies, incur lower VTE risk than RCs or open RP. They did not find studies comparing extended prophylaxis to standard prophylaxis for RPs or nephrectomies [2].

Overall, these findings are consistent with systematic reviews that estimated the procedure‐ and patient risk factor‐specific risks for 20 urological cancer procedures [3]. As these reviews suggested substantial procedure‐specific differences in the VTE risk estimates, the European Association of Urology (EAU) Guidelines provided separate recommendations for each procedure [4]. For urological (as well as gastrointestinal and gynaecological) patients, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines suggest to ‘consider extending pharmacological VTE prophylaxis to 28 days postoperatively for people who have had major cancer surgery in the abdomen’ [5]. Because of variation in both bleeding and thrombosis risks across procedures, this advice is appropriate for some procedures and misguided for others. For instance, the procedure‐specific EAU Guidelines recommend extended VTE prophylaxis for open RC but not for robot‐assisted RP without lymphadenectomy [4].

The review by Naik et al. [2] identified the lack of urology‐specific studies comparing the in‐hospital‐only prophylaxis to extended prophylaxis. The few included studies were observational with considerable limitations (e.g. limited adjustment for possible confounders).

A recent update of a Cochrane review compared the impact of extended thromboprophylaxis with low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) for at least 14 days to in‐hospital‐only prophylaxis in abdominal or pelvic surgery procedures [6]. The authors identified seven RCTs (1728 participants) evaluating extended thromboprophylaxis with LMWH and generated pooled estimates for the incidence of any VTE (symptomatic or asymptomatic) after major abdominal or pelvic surgery of 13.2% in the control group compared with 5.3% in the patients receiving extended out‐of‐hospital LMWH (odds ratio [OR] 0.38, 95% CI 0.26–0.54).

Most events were asymptomatic, although the incidence of symptomatic VTE was also reduced from 1.0% in the in‐hospital‐only group to 0.1% in patients receiving extended thromboprophylaxis (OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.08–1.11). The authors reported no persuasive difference in the incidence of bleeding complications within 3 months of surgery (defined as major or minor bleeding according to the definition provided in the individual studies) between the in‐hospital‐only group (2.8%) and extended LMWH (3.4%) group (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.67–1.81).

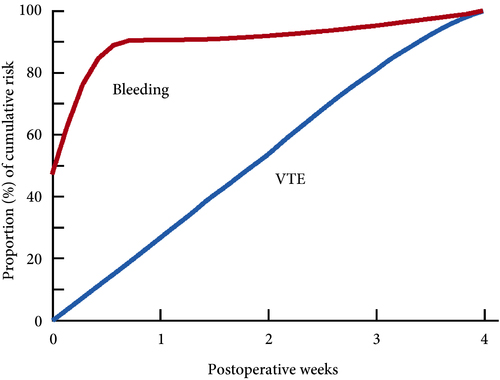

These findings are consistent with our own modelling study that demonstrated an approximately constant hazard of VTE up to 4 weeks after surgery [7]. That study also found that bleeding risk, by contrast, is concentrated in the first 4 days after surgery [7] (Fig.1). Using these findings, the EAU Guidelines suggest for patients in whom pharmacological prophylaxis is appropriate, extended pharmacological prophylaxis for 4 weeks [4]. Consistent with these recommendations, Naik et al. [2] found that 15 studies of 18 included in their review recommended extended prophylaxis.

Fig.1 Proportion of cumulative risk (%) of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and major bleeding by week since surgery during the first 4 postoperative weeks. Reproduced from: Tikkinen et al. [7].

Overall, as shown also by this review [2], the evidence base for urological thromboprophylaxis is limited. Although current evidence supports extended prophylaxis, definitively establishing the optimal duration of thromboprophylaxis will require large‐scale RCTs. Other unanswered key questions include: baseline risks of various procedures, timing of prophylaxis, patient risk stratification, as well as effectiveness of direct oral anticoagulants. In the meanwhile, suggesting extended duration to patients whose risk of VTE is sufficiently high constitutes a reasonable evidence‐based approach to VTE prophylaxis.

by Kari A.O. Tikkinen and Gordon H. Guyatt

References

- , , , , Guidelines of guidelines: thromboprophylaxis for urological surgery. BJU Int 2016; 118: 351– 8

- , , The role of extended venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for major urological cancer operations. BJU Int 2019; 124: 935-44

- , , et al. Procedure‐specific risks of thrombosis and bleeding in urological cancer surgery: systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Eur Urol 2018; 73: 242– 51

- , , et al. EAU Guidelines on Thromboprophylaxis in Urological Surgery, 2017. European Association of Urology, 2018. Accessed November 2019

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Venous Thromboembolism in over 16s: reducing the risk of hospital‐acquired deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. NICE guideline [NG89]. London: NICE, 2018. Accessed November 2019

- , , et al. Prolonged thromboprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin for abdominal or pelvic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019; 3: CD004318

- , , et al. Systematic reviews of observational studies of risk of thrombosis and bleeding in urological surgery (ROTBUS): introduction and methodology. Syst Rev 2014; 23: 150. DOI: 10.1186/2046‐4053‐3‐150.