Article of the week: The role of extended venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for major urological cancer operations

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urology community, a video prepared by the authors and a visual abstract; we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

The role of extended venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for major urological cancer operations

Rishi Naik*, Indrajeet Mandal*, Alexander Hampson†, Tim Lane†, Jim Adshead†, Bhavan Prasad Rai‡ and Nikhil Vasdev†§

*Faculty of Medical Sciences, UCL Medical School, University College London, London, †Department of Urology, Lister Hospital, Stevenage, ‡Department of Urology, Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne and §School of Life and Medical Sciences, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, UK

Rishi Naik and Indrajeet Mandal are joint first authors.

Abstract

Objectives

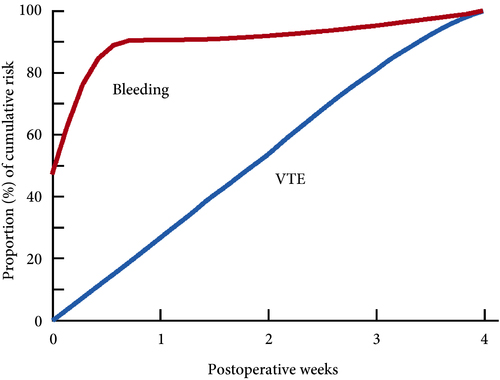

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), consisting of both pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thromboses (DVT), remains a well‐recognised complication of major urological cancer surgery. Several international guidelines recommend extended thromboprophylaxis (ETP) with LMWH, whereby the period of delivery is extended to the post‐discharge period, where the majority of VTE occurs. In this literature review we investigate whether ETP should be indicated for all patients undergoing major urological cancer surgery, as well as procedure specific data that may influence a clinician’s decision.

Methods

We performed a search of six databases (PubMed, Cochrane, EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO, and British Nursing Index (BNI)) from inception to June 2019, for studies looking at adult patients who received VTE prophylaxis after surgery for a major urological malignancy.

Results

Eighteen studies were analysed. VTE risk is highest in open and robotic Radical Cystectomy (RC) (2.6–11.6%) and ETP demonstrates a significant reduction in risk of VTE, but not a significant difference in Pulmonary Embolism (PE) or mortality. Risk of VTE in open Radical Prostatectomy (RP) (0.8–15.7%) is comparable to RC, but robotic RP (0.2–0.9%), open partial/radical nephrectomy (1.0–4.4%) and robotic partial/radical nephrectomy (0.7–3.9%) were lower risk. It has not been shown that ETP reduces VTE risk specifically for RP or nephrectomy.

Conclusion

The decision to use ETP is a fine balance between variables such as VTE incidence, bleeding risk and perioperative morbidity/mortality. This balance should be assessed for each specific procedure type. While ETP still remains of net benefit for open RP as well as open and robotic RC, the balance is closer for minimally invasive RP as well as radical and partial nephrectomy. Due to a lack of procedure specific evidence for the use of ETP, adherence with national guidelines remains poor. Therefore, we advocate further studies directly comparing ETP vs standard prophylaxis, for specific procedure types, in order to allow clinicians to make a more informed decision in future.