Article of the week: ‘Dr Google’: trends in online interest in prostate cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial and a visual abstract written by prominent members of the urological community. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this month, it should be this one.

‘Dr Google’: trends in online interest in prostate cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment

Michael E. Rezaee*, Briana Goddard†, Einar F. Sverrisson*, John D. Seigne* and Lawrence M. Dagrosa*

*Section of Urology, Department of Surgery, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, and †Geisel School of Medicine, Hanover

Abstract

Objectives

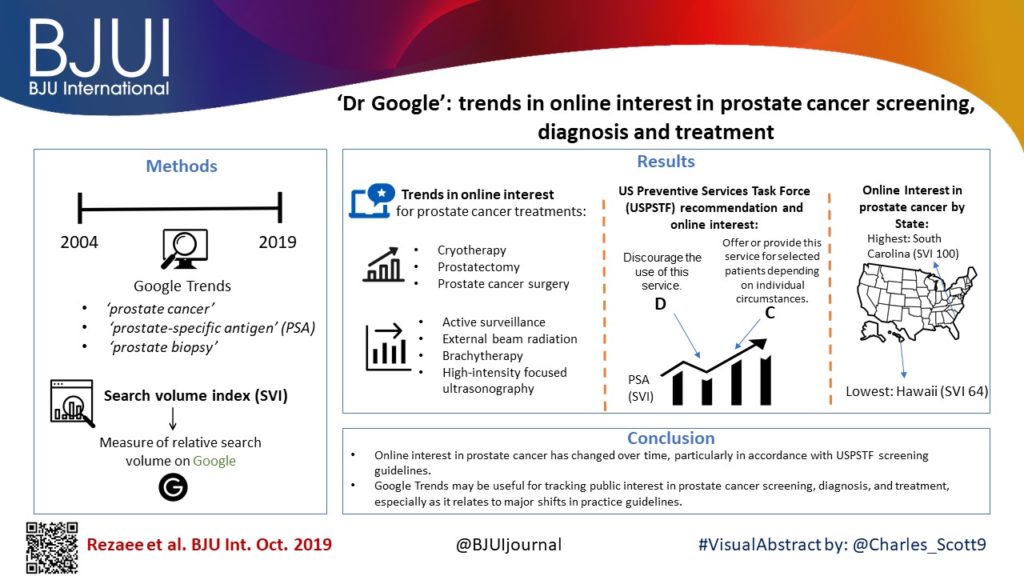

To examine trends in online search behaviours related to prostate cancer on a national and regional scale using a dominant major search engine.

Materials and Methods

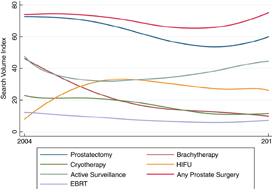

Google Trends was queried using the terms ‘prostate cancer’, ‘prostate‐specific antigen’ (PSA), and ‘prostate biopsy’ between January 2004 and January 2019. Search volume index (SVI), a measure of relative search volume on Google, was obtained for all terms and examined by region and time period: pre‐US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Grade D draft recommendation on PSA screening; during the active Grade D recommendation; and after publication of the recent Grade C draft recommendation.

Results

Online interest in PSA screening differed by time period (P < 0.01). The SVI for PSA screening was greater pre‐Grade D draft recommendation (82.7) compared to during the recommendation (74.5), while the SVI for PSA screening was higher post‐Grade C draft recommendation (90.4) compared to both prior time periods. Similar results were observed for prostate biopsy and prostate cancer searches. At the US state level, online interest in prostate cancer was highest in South Carolina (SVI 100) and lowest in Hawaii (SVI 64). For prostate cancer treatment options, online interest in cryotherapy, prostatectomy and prostate cancer surgery overall increased, while searches for active surveillance, external beam radiation, brachytherapy and high‐intensity focused ultrasonography remained stable.

Conclusion

Online interest in prostate cancer has changed over time, particularly in accordance with USPSTF screening guidelines. Google Trends may be a useful tool in tracking public interest in prostate cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment, especially as it relates to major shifts in practice guidelines.