Another good week for radical prostatectomy

The SPCG-4 (Bill-Axelson) study updated again in NEJM

In this week’s edition of the NEJM, Anna Bill-Axelson and the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study Number 4 (SPCG-4) investigators have written an impressive update to their famous study comparing radical prostatectomy (RP) to watchful waiting (WW) in a setting of mostly clinically detected prostate cancer. In 2002, the group reported in NEJM at a median 8 years of follow-up that RP reduces disease specific mortality, overall mortality, and risk of metastasis and local progression. The declines in prostate cancer specific mortality were 8.6% for RP versus 14.4% for WW. In 2011, they published again with a median 12.8 years of follow-up and the differences were 14.6% versus 20.7%, but the benefit was impressively driven by men under age 65. Now in 2014, the median follow-up time is 13.4 years with up to 23.2 years at the high end, and overall 64% of the cohort has died by end of 2012 — specific to prostate cancer in 17.7% vs. 28.7%. The number needed to treat is 8.

In this week’s edition of the NEJM, Anna Bill-Axelson and the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study Number 4 (SPCG-4) investigators have written an impressive update to their famous study comparing radical prostatectomy (RP) to watchful waiting (WW) in a setting of mostly clinically detected prostate cancer. In 2002, the group reported in NEJM at a median 8 years of follow-up that RP reduces disease specific mortality, overall mortality, and risk of metastasis and local progression. The declines in prostate cancer specific mortality were 8.6% for RP versus 14.4% for WW. In 2011, they published again with a median 12.8 years of follow-up and the differences were 14.6% versus 20.7%, but the benefit was impressively driven by men under age 65. Now in 2014, the median follow-up time is 13.4 years with up to 23.2 years at the high end, and overall 64% of the cohort has died by end of 2012 — specific to prostate cancer in 17.7% vs. 28.7%. The number needed to treat is 8.

What stands out in the latest edition of this famous trial? Although previous reports describe differences in metastatic and progressive disease in WW, this report nicely shows that RP reduces metastatic disease burden, androgen deprivation therapy, and palliative treatments across all age groups — even if mortality comparisons are still more notable in younger cohorts. So the paper has evolved into a key lesson in the natural history of prostate cancer and localized curative intervention (side debate — this paper is not really about radical prostatectomy itself, but rather intervention, and I would assume many similar benefits possible with radiation approaches). Prostate cancer outcomes are more complex than simple cure fractions. Patients can suffer from relapsed disease, multiple treatments, long-term androgen deprivation, and, yes, actual prostate cancer mortality that apparently takes a committee of experts to decipher from competing sources. I think the impact of the study will be that healthy men between the ages of 65-75 may benefit from treatment of lethal potential prostate cancer — but perhaps as measured by endpoints other than mortality. This is especially relevant with the evolving library of treatment options for castrate resistant prostate cancer — it may take a lot longer to actually die of prostate cancer, but who really wants to spend their last 5-10 years of life heavily medicated compared to a more effective localized intervention at an earlier time? Between earlier versions of this study and the PIVOT trial, I think we already believe in the benefits of curative therapy for men <65 years with intermediate to high-risk disease. On the other end of the spectrum, the paper still supports the concept of active surveillance for low risk cancer, although more is to be learned from other accruing cohorts of patients who will undergo selective delayed intervention.

Overall, I found this to be a highly citable paper with a new set of figures destined for use in many PowerPoint talks to come. The overall message is that RP at the right time and right patient can prevent mortality and disease progression. A comprehensive prostate cancer program should start with such biology-based discussions with patients and then carefully integrate active surveillance in the lower risk end and clinical trials of combination therapy at the higher end. Finally, I wonder if the findings of reduced metastatic events in older patients might re-challenge the screening guidelines that are encouraging less screening after age 70?

John W. Davis, MD

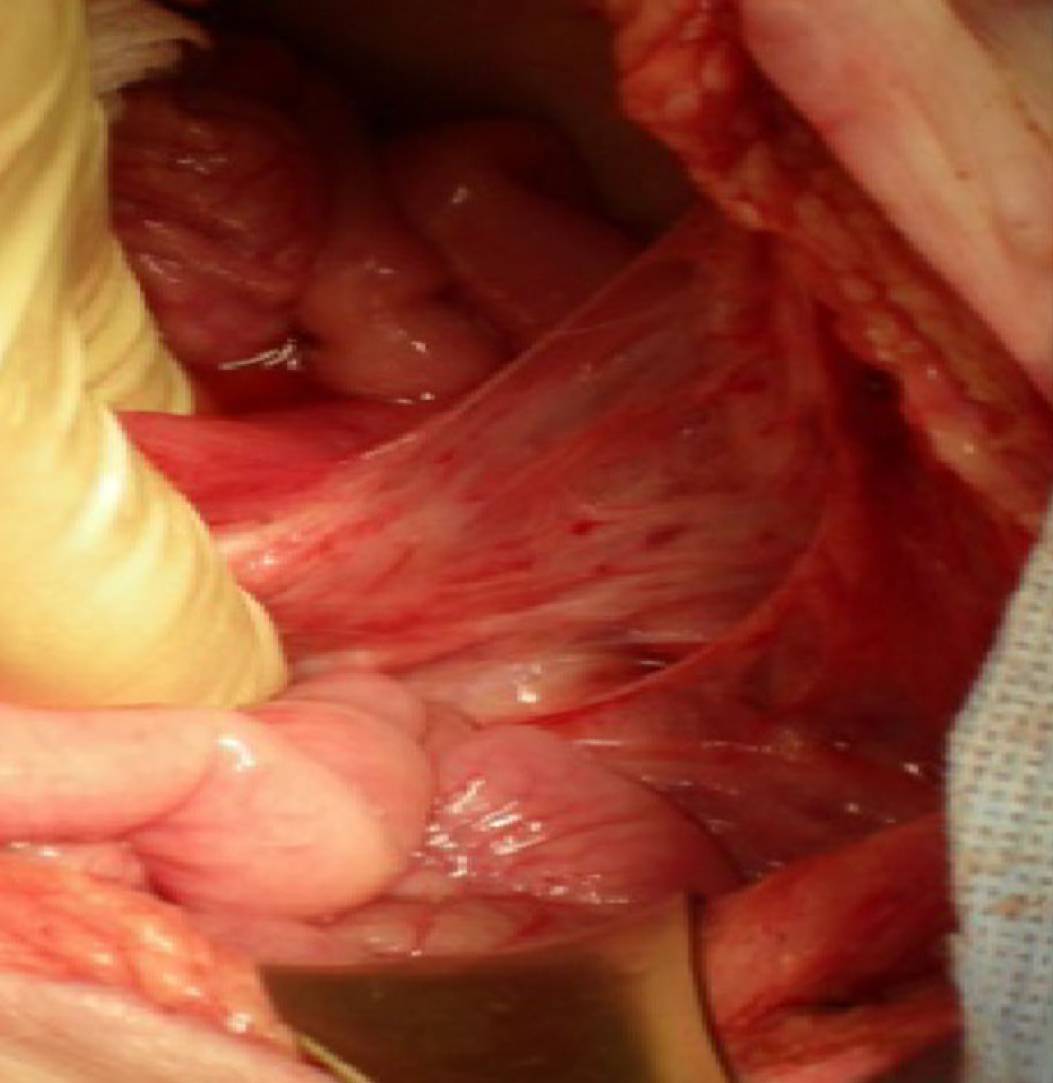

Associate Editor, BJUI

There are many terrifying anecdotes relating to the use of ketamine and the damage that sustained daily use may cause to the urinary tract. These include those reported in the medical literature and through the wider media. Reports of ketamine-related deaths, memory loss, hepatobiliary damage, ureteric obstruction with renal failure and profound bladder pain. Use is recorded in teenagers with the ability for a child to demonstrate symptoms to their peers becoming a badge of honour. At UCLH we are working closely with colleagues to provide improving care for this new disease. We have links with the Club Drug clinic in London and Lifeline, another drug support agency. We aim to help patients come off ketamine and re-assess their symptoms once that is true – a few patients have needed major surgery but many have recovered well without.

There are many terrifying anecdotes relating to the use of ketamine and the damage that sustained daily use may cause to the urinary tract. These include those reported in the medical literature and through the wider media. Reports of ketamine-related deaths, memory loss, hepatobiliary damage, ureteric obstruction with renal failure and profound bladder pain. Use is recorded in teenagers with the ability for a child to demonstrate symptoms to their peers becoming a badge of honour. At UCLH we are working closely with colleagues to provide improving care for this new disease. We have links with the Club Drug clinic in London and Lifeline, another drug support agency. We aim to help patients come off ketamine and re-assess their symptoms once that is true – a few patients have needed major surgery but many have recovered well without.