We present a case of a young man referred to our hospital with severe haematuria, pre-renal lipoma and lumbar pain.

Authors: Navarro, Joaquin; Azua-Romeo, Javier; Tovar, Maria Teresa; Lpoez Lopez, Jose Antonio; Ernest Lluch Hospital, Urology, Calatayud, Zaragoza, Spain

Corresponding Author: Javier Azua-Romeo, Ernest Lluch Hospital, Urology, Calatayud, Zaragoza, Spain. Email: [email protected]

Abstract

Objective

Nutcracker syndrome is the consequence of compression between the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta over the left renal vein. Its manifestations are very varied and nonspecific, therefore, this syndrome may be misdiagnosed. There are several different treatment options, from conservative management to surgery.

Method

Here, we present a case of a young man referred to our hospital with severe haematuria, pre-renal lipoma and lumbar pain. The literature from 1950 onwards has been reviewed and the discussion regarding this unusual syndrome has been summarized.

Results

After undergoing surgical treatment (left renal vein transposition), our patient is asymptomatic, with complete resolution of his symptoms.

Conclusions

Due to the rarity of this syndrome and it being usually asymptomatic, it may be underdiagnosed. Following accurate diagnosis and, treatment, the symptoms usually resolve.

Introduction

Nutcracker Syndrome is the consequence of compression between the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta over the left renal vein (mesoaortic entrapment). It results in dilation of the vein and the appearance of varicosities in the renal pelvis as well as in the ureteric and gonadal veins1. In general terms, variants of the retroperitoneal vasculature are rare, even though, due to current imaging technologies, it is possible to diagnose these abnormalities, which otherwise could remain unnoticed.

The first reference to the condition dates from 1950 in a paper by by El Sadr and Mine. Nevertheless, it was De Schepper who named it the Nutcracker Syndrome (renal vein entrapment syndrome)1, comparing the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery with the arms of a nutcracker that compress the left renal vein, inducing, due to the difficulty of venous return of the left kidney, left renal venous hypertension, venous stasis and congestion of the kidney.

Here, we present a new case of Nutcracker Syndrome in a young male patient who came to our Hospital with severe lumbar pain and macroscopic haematuria requiring blood transfusion, and who presented with a huge lipoma adjacent to his left kidney which aggravated his symptoms.

Case Report

Our case is a 17 year-old male patient without significant medical history who was referred with dull left lumbar pain occasionally radiating to the left flank, which had lasted several months. The pain was eased by analgesia. The episodes of pain had gradually become more frequent and intense and recently had been associated with gross haematuria. During each episode the patient remained afebrile and hemodynamically stable, although on one occasion it was necessary to transfuse two units of packed red cells due to his being anaemic.

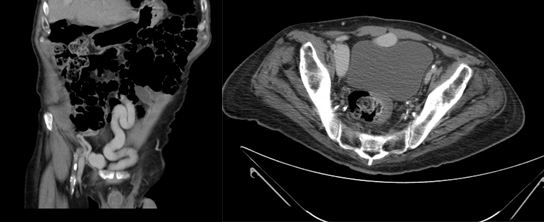

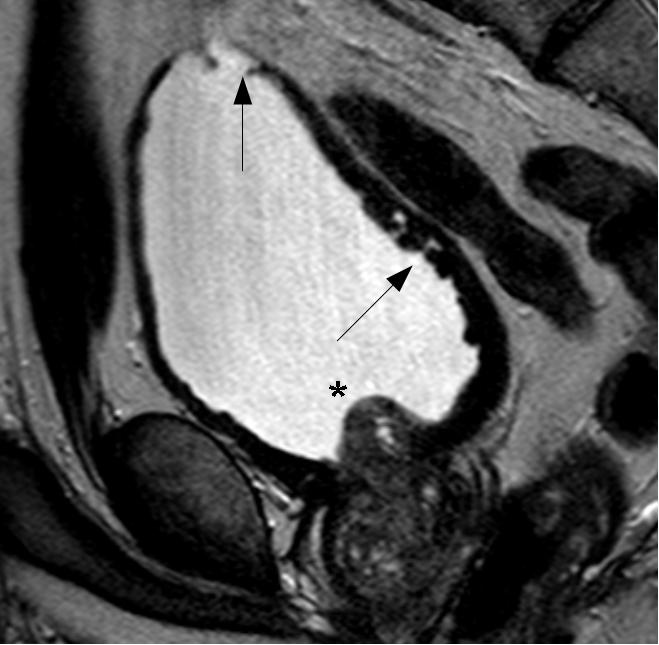

On examination, the patient has a mild left varicocele. Blood tests revealed a low hematocrit and haemoglobin, and proteinuria was found on urinalysis. Ultrasonography and urography did not demonstrate any significant findings, so a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was requested to further investigate his hematuria. Images revealed that the left renal vein was of large calibre. A large lipoma displacing the left kidney was also visible, accentuating the angle of the renal vein as it passed behind the superior mesenteric artery (Figure 1).

Figure 1 A: Abdominal CT image showing a large calibre left renal vein compressed between the abdominal aorta and superior mesenteric artery, and a large lipoma adjacent to the left kidney

B: Postoperative image showing the left renal vein now of normal size.

Given these findings and the severity of the patient’s symptoms, the lipoma was removed. This was performed via a subcostal approach in order to mobilise the left kidney. Since the removal of the lipoma allowed mobilization of the kidney, to relieve the compression of the aorto-mesenteric clamp on the left renal vein, this was transposed approximately two centimeters caudally to the left lateral side of the inferior vena cava.

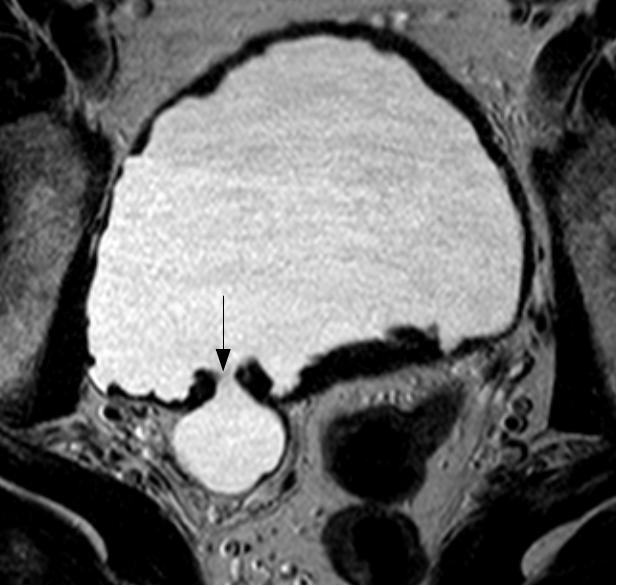

The surgery and the immediate postoperative course were uneventful, allowing the patient to be discharged on the third postoperative day (Figure2).

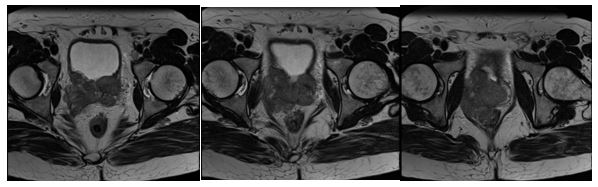

Figure 2. Intraoperative image: The left renal vein and superior mesenteric artery.

Follow up CT scan has shown that the technique is effective, demonstrating the left renal vein to have a normal diameter. The patient remains completely asymptomatic.

Discussion

In 1950, Mina and El-Sadr described a secondary varicocele due to compression by the superior mesenteric artery of the left renal vein, thereby hampering venous return dependent on the left renal vein, resulting in varicose pelvic, ureteral and gonadal veins. Nutcracker syndrome has been classified as: Anterior, if compression is due to the superior mesenteric artery (often associated with renal ptosis or an abnormal origin of the superior mesenteric artery) and Posterior3 (or Nutcracker pseudosyndrome) if the compression occurs between the aorta and vertebral bodies, usually caused by the persistence of the posterior branch of fetal periaortic vascular ring1.

Epidemiologically, this entity occurs more frequently in women and is diagnosed within the 3rd and 4th decade of life, our case however was in a 17 year-old male. It is difficult to define the exact incidence and prevalence of Nutcracker Syndrome since the majority of patients are asymptomatic, and are diagnosed incidentally on imaging ordered for other reasons. Despite this, our patient suffered severe lumbar pain and macroscopic haematuria which required a blood transfusion, and presented with a huge lipoma which aggravated the symptoms.

Overall, when abdominal CT and ultrasound were reviewed, 72% showed compression of the renal vein between aorto-mesenteric clamp, although most patients would be, as already stated, asymptomatic10.

The typical clinical manifestations include back pain occasionally radiating to the gluteal area and hematuria (macro or microscopic), in few cases, patients develop anemia which may require blood transfusion. Other signs and symptoms may include proteinuria,6 hypertension, orthostatic hypotension, fatigue and weakness. Physical examination may demonstrate the presence of varicocele in males and pelvic varicose veins in females with symptoms of chronic pelvic pain or dysmenorrhea5. Also arteriovenous fistulas associated with Nutcracker Syndrome have been described.

Often the diagnosis is reached by exclusion. As with any other condition, assessment begins with the history and exploration. The findings of laboratory results are nonspecific. With regard to imaging studies, it is usual start with an abdominal ultrasound due to its utility, safety and low cost. On ultrasound, the renal pedicle can be seen with a dilated vein and slightly enlarged kidney due to renal congestion. The next step would be a diagnostic CT or MRI. Both could be demonstrate the presence of a greater angulation in the superior mesenteric artery leaving the abdominal aorta, trapping the left renal vein 4, 9.

With regard to more invasive investigations, retrograde venography and video angiography to determine the renocaval pressure gradient will give a precise diagnosis of aorto-mesenteric clamp. Venography will demonstrate the area where the compression is, the existence of collateral circulation in periureteral vessels, reflux into the renal vein branches (adrenal vein and gonadal vein) and the stagnation of contrast in the renal vein. The pressure gradient between the renal vein and cava must be greater than 1 mm Hg to lead to a diagnosis of the Nutcracker syndrome, since the normal value is stated as between 0 and 1, nevertheless in advanced cases of Nutcracker Syndrome, due the development of collateral circulation, the gradient might be normal7.

After confirming the diagnosis of Nutcracker Syndrome different treatment alternatives can be chosen taking into account the symptoms of each individual patient. In asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic cases, expectant treatment may be an option, even moreso in younger patients where spontaneous resolution might be expected2.

Amongst conventional open surgery, autotransplantation, transposition of the renal vein, renal vein bypass or renal vein and fixation and medialization through nephropexy could be considered7.

Using open or laparoscopic surgery, and with good outcome in the short term, an extravascular prosthesis could be placed (ring-reinforced PTFE). It will enhance the renal vein and prevent the collapse of the portion between the renal vein and aorto-mesenteric clamp. This technique was described for the first time in 1988 by Barnes. Utilising interventional radiology techniques, endovascular stents can be placed. The medical literature describes good outcomes with endovascular stents, in terms of the disappearance of symptoms, although this technique is not exempt from complications (proximal migration, embolism and thrombosis of the prosthesis). This technique requires the mandatory prescription of antiplatelet therapy with the risks this entails7, 8.

Conclusions

Nutcracker Syndrome is a rare entity, and is due to the compression exerted on the left renal vein from the clamp that forms from the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta. The usual clinical presentation is lumbar pain and haematuria. This is most frequent in females among in their fourth decade of life. However, it is more usual for patients to be asymptomatic, and this group do not require treatment. In most cases, common imaging techniques will confirm the diagnosis and it is rarely necessary to undertake invasive techniques such as venography. Usually treatment is minimally invasive, although open techniques are cited in the literature. In asymptomatic patients, especially if they are young, expectant treatment is the best option.

References

1. Ahmed K, Sampath R, Khan MS. Current trends in the diagnosis and management of renal nutcracker syndrome: a review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006; 31(4):410-416.

2. El Harrech Y, Jira H, Chafiki J, Ghadouane M, Ameur A, Abbar M. Actitud expectante en el Síndrome del Cascanueces. Act Urol Esp 2009;33(1):93-96

3. Muller Arteaga C, Martín Martín S, Cortiñas González J R, González Fajardo J A ,Fernández del Busto E. Síndrome del cascanueces posterior: Vena renal retroaórtica asociada a fístula arteriovenosa y carcinoma renal. A propósito de un caso y revisión de la literatura. Act Urol Esp 2009;33(1):101-104.

4. Bass JE, Redwine MD, Kramer LA, Huynh PT, Harris JH Jr. Spectrum of Congenital Anomalies of the Inferior Vena Cava: Cross-sectional Imaging Findings. Radiographics. 2000; 20(3): 639-652.

5. Gutiérrez E, Hernández E, Sánchez-Guerrero A, Morales E, Gutiérrez-Solís E, Praga M. Mujer de 29 años con microhematuria persistente y episodios de hematuria macroscópica. NefroPlus 2008; 1(2):33-36.

6. Chang CT, Hung CC , Ng KK, Yen TH. Nutcracker syndrome and left unilateral haematuria. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005; 20: 460-461.

7. Zhang H, Li M, Jin W, San P, Xu P, Pan S. The left renal entrapment syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Ann Vasc Surg 2007; 21: 198-203.

8. Santos Arrontes D, Salgado Salinas R, Chiva Robles V, Gómez Vicente JM, Fernández González J, Costa Subías J. Síndrome del Cascanueces. A propósito de un caso y revisión de la literatura. Actas Urol Esp. 27 (9): 726-731, 2003.

9. Martínez-Salamanca I, Herranz Amo F, Gordillo Gutierrez I, Díez Cordero JM, Subirá Ríos D. Síndrome Nutcracker o Cascanueces: Demostración mediante TAC helicoidal con reconstrucción 3D. Actas Urol Esp. 28 (7): 549-552, 2004.

10. Russo D, Minutolo R, Laccarino V, Andreucci M, Capuano A, Savino F. Gross Hematuria of Uncommon Origin: The Nutcracker Syndrome Am J of Kid Dis, Vol 32, No 3, 1998.

Date added to bjui.org: 27/01/2012

DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2011-092-web