We read with great interest the publication on the side‐specific multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI)‐based nomogram from Martini et al. [1].

The prediction of extracapsular extension (ECE) of prostate cancer is of utmost importance to inform accurate surgical planning before radical prostatectomy (RP).

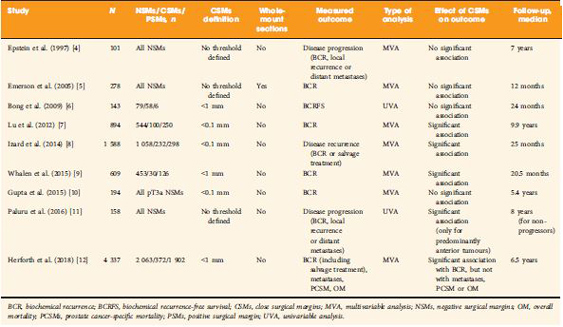

Today, surgical strategy is tailored to the patient’s characteristics, and the need for a correct prediction of ECE is of paramount importance to guarantee oncological safety, as well as optimal functional outcome. The most up‐to‐date guidelines suggest referring to nomograms to decide whether or not to perform nerve‐sparing (NS) surgery. Since the first version of the Partin Tables in 1993, several models have been developed based on PSA, Gleason score at prostate biopsy, and clinical staging, as the most used covariates.

Furthermore, mpMRI is increasingly used in the diagnostic pathway of prostate cancer to aid prostate biopsy targeting and to attain a more accurate diagnosis of clinically significant prostate cancer. Despite its recognised role in the detection of cancer, the accuracy for local staging is poor, providing a low and heterogeneous sensitivity for the detection of ECE [2].

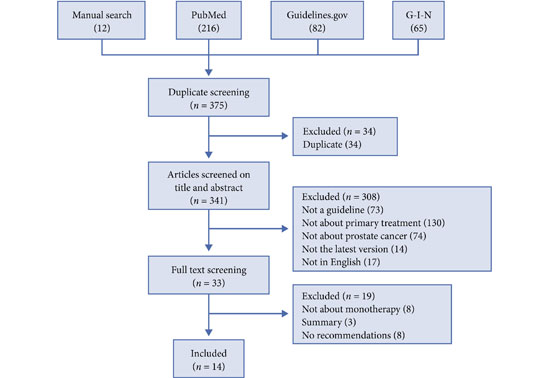

Given this limitation, the addition of MRI to clinically derived nomograms might result in an improved assessment of preoperative local staging. In a retrospective analysis of 501 patients who underwent RP, MRI + clinical models outperformed clinical‐based models alone for all staging outcomes, with better discrimination in predicting ECE with MRI + Partin Tables and MRI + Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment (CAPRA) score than nomograms alone [3].

In the current article, Martini et al. [1] suggest a novel nomogram for predicting ECE that includes the presence of a ‘documented definite ECE at mpMRI’ as an additional variable beyond PSA, Gleason score, and maximum percentage of tumour in the biopsy core with the highest Gleason score. Readers should recognise that this is the first model integrating side‐specific MRI findings together with side‐specific biopsy data to provide a ‘MRI‐based side‐specific prediction of ECE’, in an effort to support the surgical decision for a uni‐ or bilateral NS approach.

However, given the frail generalisability of nomograms in different datasets even after external validation [4], a predictive tool has to be built on a rigorous methodology with clear reproducibility of all steps the covariates derive from.

In this respect, the current model raises some concerns.

The schedule of preoperative MRI assessment is arbitrary, with imaging being performed either before (23.9%) or after systematic biopsy (76.1%), and amongst patients with a MRI prior to biopsy, only 94 of 134 patients underwent additional targeted sampling. As a result, MRI is applied by chance in three different ways: before prostate biopsy without targeted sampling, before prostate biopsy with targeted sampling, and after prostate biopsy.

Based upon this heterogeneous MRI timing, the performance of such a model in a novel population may be biased depending on the diagnostic pathway applied at each institution.

The choice of the variables included represents another point of concern. The output of two out of four covariates, ECE depiction at mpMRI and the percentage of tumour in the biopsy core, have been deliberately dichotomised, without taking into account the continuous trend intrinsic to both variables.

Actually, local staging in the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) guidelines has been scored on a 1–5 point scale to grade the likelihood of an ECE event. The authors deliberately dichotomised mpMRI findings, considering ‘the loss of prostate capsule and its irregularity’ as suggestive of ECE and ‘broad capsular contact, abutment or bulge without gross ECE’ evocative of organ‐confined disease. As a result, the included MRI covariate may account for a gross prediction of ECE, maintaining the inaccurate and inter‐reader subjective interpretation of local staging intrinsic to MRI.

Beyond those methodological concerns and the moderate sample size that may limit the reproducibility of the model, we wonder if such a prediction really assists the surgeon’s capability to perform a tailored surgery.

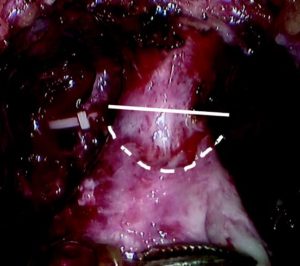

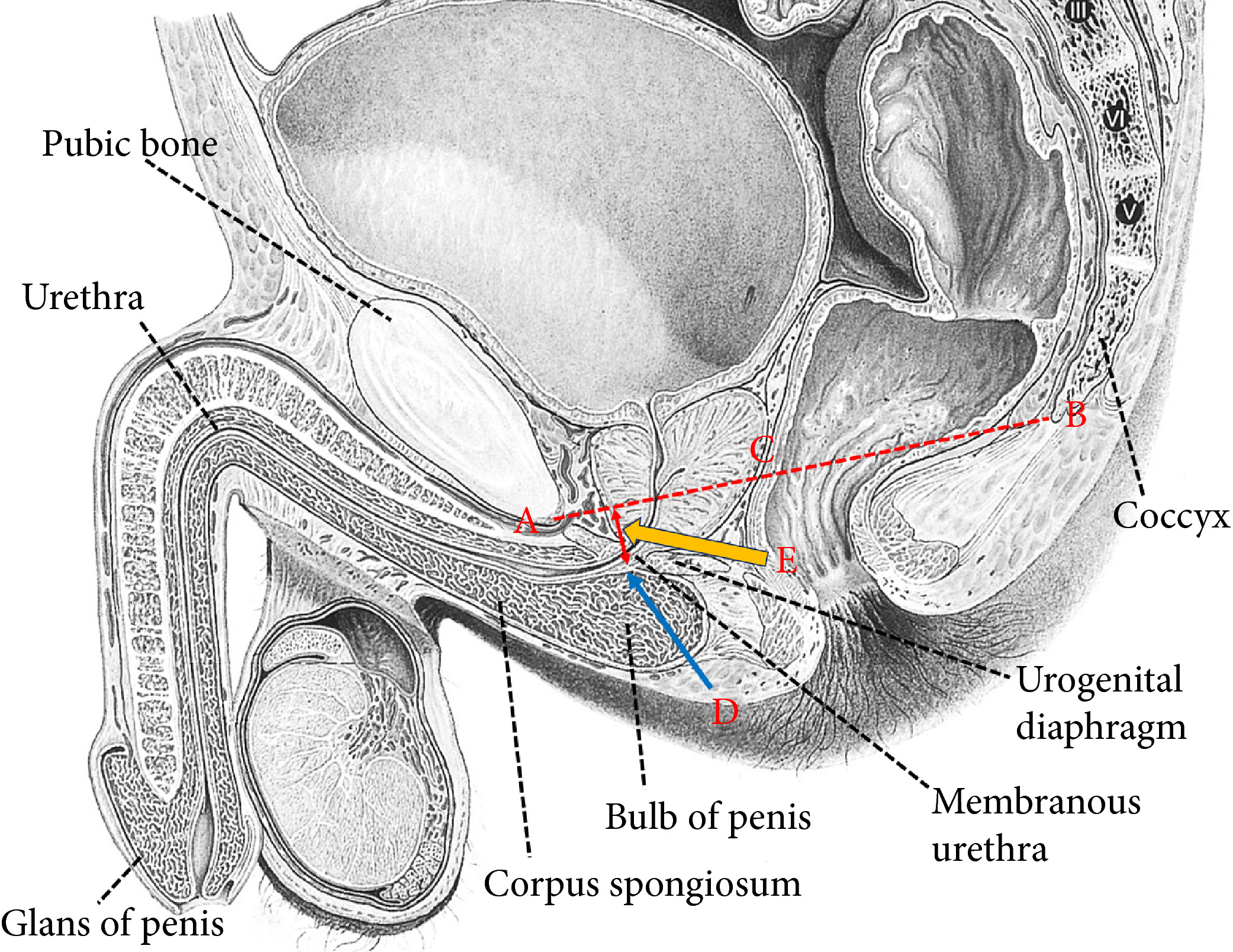

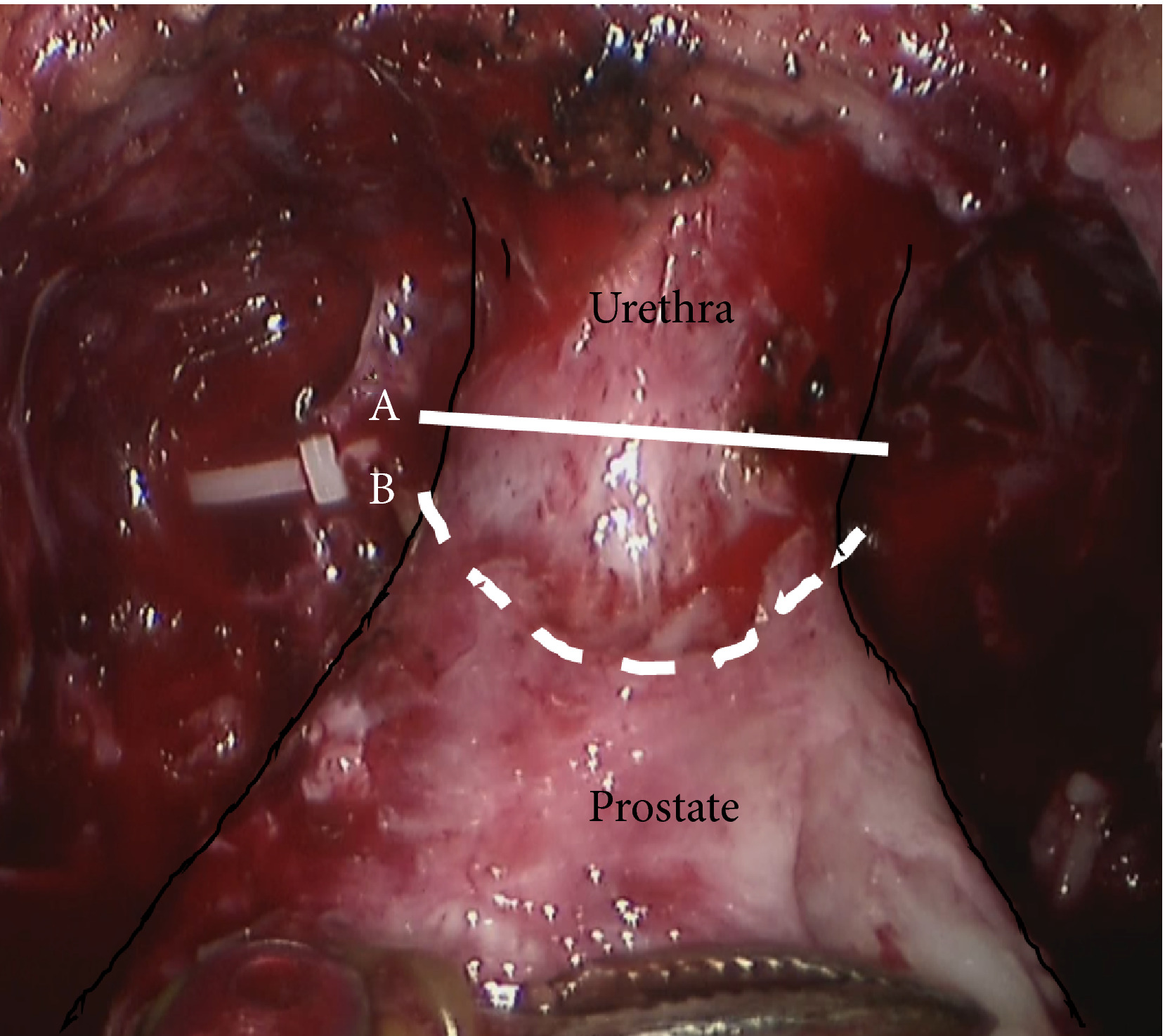

The ‘all or none’ era of NS surgery is over, and we are currently able to grade NS according to different approaches reported in the literature. Particularly, Tewari et al. [5] proposed a NS approach based on four grades of dissection, with the veins on the lateral aspect as vascular landmarks to gain the correct dissection planes. Patel et al. [6] described a five‐grade scale of dissection, using the arterial periprostatic vasculature as a landmark to the same purpose.

If we are able to grade a NS surgery, the prediction of ECE should be graded as well and should answer the prerequisite of knowing the amount of prostate cancer extent outside the capsule. How does a surgeon make the decision to follow a more or less conservative dissection otherwise?

We tried to address this issue by using a tool aimed at predicting the amount of ECE [the Predicting ExtraCapsular Extension in Prostate cancer tool] [6] and supporting the choice of the correct plane of dissection with a suggested decision rule. In our study, developed on a large sample of nearly 12 000 prostatic lobes and several combined clinicopathological variables, the absence of imaging characterization was the major point of weakness.

To date, the ideal predictive tool has yet to be described. However, in the modern era of precision surgery, we think that a model should encompass the surgical knowledge and techniques currently available.

Future developments will probably include three‐dimensional surgical navigation models displayed on the TilePro™ function of the robotic console (Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA), based on the integration of MRI (for the number, size and location of disease) and predictive tools (to define the amount of ECE).

References

- Martini A, Gupta A, Lewis SC et al. Development and internal validation of a side‐specific, multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging‐based nomogram for the prediction of extracapsular extension of prostate cancer. BJU Int 2018; 122: 1025–33

- de Rooij M, Hamoen EH, Witjes JA, Barentsz JO, Rovers MM. Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging for local staging of prostate cancer: a diagnostic meta‐analysis. Eur Urol 2016; 70: 233–45

- Morlacco A, Sharma V, Viers BR et al. The incremental role of magnetic resonance imaging for prostate cancer staging before radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol 2017; 71: 701–4

- Bleeker SE, Moll HA, Steyerberg EW et al. External validation is necessary in prediction research: a clinical example. J Clin Epidemiol 2003; 56: 826–32

- Tewari AK, Srivastava A, Huang MW et al. Anatomical grades of nerve sparing: a risk‐stratified approach to neural‐hammock sparing during robot‐assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP). BJU Int 2011; 108: 984–92

- Patel VR, Sandri M, Grasso AA et al. A novel tool for predicting extracapsular extension during graded partial nerve sparing in radical prostatectomy. BJU Int 2018; 121: 373–82