Posts

Editorial: Extent of lymph node metastases

The role of prostatectomy in lymph node metastasized prostate cancer has been subject to changing opinions. Classically, a nodal dissection was performed as the initial step in the procedure and prostatectomy was avoided in men with cryosection-proven metastases. Biochemical recurrence during the first 3 years occurs in the majority of men with pN1 disease [1]. Early data from randomized trials shows only a 50% prostate cancer-specific survival 12 years after prostatectomy and nodal metastases without immediate adjuvant treatment [2]. Recently, Passoni et al. [3] showed a higher 10-year overall survival of 82.8% in men with nodal metastases, of whom the majority were treated with adjuvant androgen ablation and/or radiotherapy. This percentage is remarkably similar to the treatment arm of the earlier-mentioned study reported by Messing et al. [2], which showed a 10-year disease-specific survival of >80%. At 10 years about half the patients who died, did so from prostate cancer; therefore, although reasonable intermediate range survival can be obtained in men with nodal metastases of prostate cancer, the major cause of death remains prostate cancer when surgery is applied at the age of 65 years. Although adjuvant androgen ablation may improve survival, as suggested by the above-mentioned observations, some men may not experience recurrence after resection of nodal metastases and would experience the toxicity of androgen ablation unnecessarily. The identification of these men would reduce costs and toxicity.

Passoni et al. [3] presented a multicentre study on prognostic factors after prostatectomy for node-positive disease. The number of removed nodes (median 10) seems relatively low compared with the 17 reported in their earlier single-centre study, but may be a good reflection of urological practice in general. By comparison, the percentage of men who underwent adjuvant radiotherapy in the multicentre study was low (16%). Data from da Pozzo et al. [4] suggest that adjuvant radiotherapy may be of benefit in men with limited nodal metastases. It would be of interest to study whether men with a later biochemical recurrence would be those that did experience recurrence only locally and therefore would be those most likely to benefit from adjuvant (or salvage) radiotherapy.

In the current study by Passoni et al. [1] in the BJUI, the follow-up was relatively short (16 months). Earlier data from this author group showed that number of positive nodes and lymph node density were good predictors of cancer-specific survival after prostatectomy. This earlier observation is now confirmed in a multicentre analysis with a different endpoint: biochemical recurrence. What is notable is the fact that this confirmation was obtained in a series of patients with fewer nodes removed. The value of the marker ≤2 positive nodes becomes limited with the observation that this group contained 85% of men in their series. The second marker found, the size of the node, showed a more general distribution but as a single marker had no predictive value. The differences in Harrel’s c values from the base model containing other clinical characteristics are limited and reproducibility of measures needs attention. Still, the observation that extent of nodal metastases is of prognostic value after surgery is notable.

Ideally, markers could predict the absence of further disease progression in men after prostatectomy for nodal metastasized prostate cancer. None of the studied characteristics fulfill this need because at 36 months after prostatectomy the majority of men, even those in the best prognostic group, do experience biochemical recurrence that will result in prostate cancer-related death. Gleason score is a strong predictor of the presence of nodal metastases [5], and some have suggested that nodal Gleason grade is of prognostic value in men with pN+ disease. Until these markers have been further evaluated, it remains important to address the fact that reported cancer-specific survival in most men with pN+ disease is >10 years [6]. Although tempting to speculate that prostatectomy and (extended) lymph node dissection plays a role in this, the almost inevitable development of biochemical recurrence reported in the current study by Passoni et al. [1], even in patients in the best prognostic group, stresses the systemic nature of this disease which will require a multimodality approach in most men at some point.

Henk G. van der Poel

Department of Urology, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

References

1 Passoni N, Fajkovic H, Xylinas E. Prognosis of patients with pelvic lymph node metastasis following radical prostatectomy: value of extranodal extension and size of the largest lymph node metastasis. BJU Int 2014; 114: 503–10

2 Messing EM, Manola J, Yao J et al. Immediate versus deferred androgen deprivation treatment in patients with node-positive prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. Lancet Oncol 2006; 7: 472–9

3 Passoni NM, Abdollah F, Suardi N et al. Head-to-head comparison of lymph node density and number of positive lymph nodes in stratifying the outcome of patients with lymph node-positive prostate cancer submitted to radical prostatectomy and extended lymph node dissection. Urol Oncol 2013; 29: 29.e21–8

4 Da Pozzo LF, Cozzarini C, Briganti A et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with prostate cancer and nodal metastases treated by pelvic lymphadenectomy and radical prostatectomy: the positive impact of adjuvant radiotherapy. Eur Urol 2009; 55: 1003–11

5 Ross HM, Kryvenko ON, Cowan JE, Simko JP, Wheeler TM, Epstein JI. Do adenocarcinomas of the prostate with Gleason score (GS)</=6 have the potential to metastasize to lymph nodes? Am J Surg Pathol 2012; 36: 1346–52

6 Touijer KA, Mazzola CR, Sjoberg DD, Scardino PT, Eastham JA. Long-term outcomes of patients with lymph node metastasis treated with radical prostatectomy without adjuvant androgen-deprivation therapy. Eur Urol 2013; 65: 20–5

What’s the Diagnosis?

Test yourself against our experts with our weekly quiz. You can type your answers here if you want to compare with our answers, or just click the ‘submit’ button below.

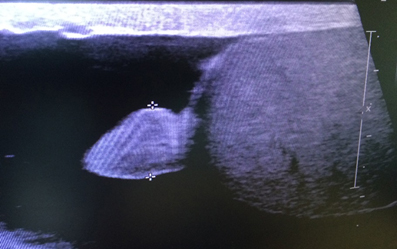

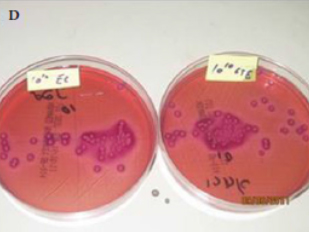

This image is from a recent paper by Rosenberg et al. BJUI 2014 that explores the effect of intravesical instillation of green tea extract (GTE) on a rat model of bacterial cystitis.

No such quiz/survey/pollRocktober – Keep on rocking #urojc

We celebrated the two-year anniversary of the international urology journal club this month (@iurojc) with record participation. There were over 500 tweets in the 48 hour discussion of this month’s article, published in New England Journal of Medicine on September 18, 2014, Ultrasound versus Computed Tomography for Suspected Nephrolithiasis. It was a true multidisciplinary discussion with nephrologists, EM docs, and study author, radiologist Rebecca Smith-Bindman tweeting.

We celebrated the two-year anniversary of the international urology journal club this month (@iurojc) with record participation. There were over 500 tweets in the 48 hour discussion of this month’s article, published in New England Journal of Medicine on September 18, 2014, Ultrasound versus Computed Tomography for Suspected Nephrolithiasis. It was a true multidisciplinary discussion with nephrologists, EM docs, and study author, radiologist Rebecca Smith-Bindman tweeting.

This was a multi-institutional prospective randomized control study evaluating bedside and radiology ultrasonography versus CT as the first test performed for patients presenting to the ED with flank or abdominal pain. Patients who initially underwent ultrasound could also receive a CT if the provider felt necessary based on clinical presentation and ultrasound findings. In terms of the primary endpoints, authors found no significant difference across the three groups in high-risk diagnoses with complications related to missed or delayed diagnoses. There was significantly less 6-month cumulative radiation exposure in patients assigned to the ultrasonography groups compared to those assigned to CT. Conclusions of this study in the form of a tweet: Get US first #noharmdone #lessradiation.

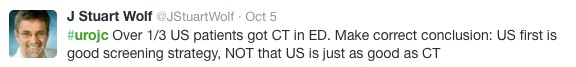

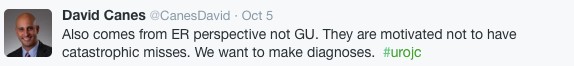

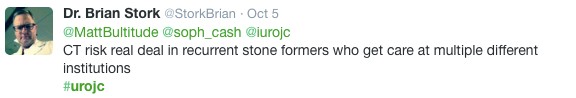

Conversation first focused on clarifying the main conclusions of this article. Notably, ED physicians were the focus of this study, who care whether the patient will be admitted or sent home. Information about size, location, etc of stones was omitted from the study since the goal was not definitive stone treatment.

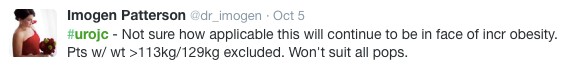

Some of the limitations of the study were brought up early on. First of all, obese patients were excluded (men >129 kg and women >113 kg).

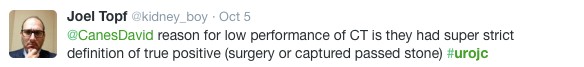

Additionally, the definition of being diagnosed with a stone only applied to individuals who reported passing a stone or having a stone surgically removed.

Much of the conversation focused on how this approach may be beneficial in recurrent stone-formers, although at least a KUB likely needed before taking a patient to the OR.

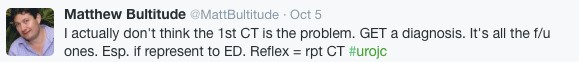

One of the main issues seemed to be the practicality of universally applying the “ultrasound first” approach. Many institutions do not have ultrasound readily available during night or weekend hours.

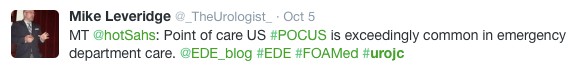

ER folks disagreed, and thought that point-of-care ultrasound could be easily adopted.

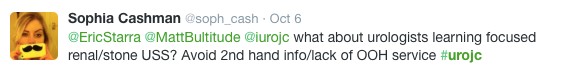

@soph_cash suggested urologists be the ones to perform ultrasound. Although an important skill to learn, the idea was quickly put to rest.

Author Rebecca Smith-Bindman made a brief appearance in support of the evidence in the study.

Coincidentally, the twitter-based nephrology journal club, #nephjc, discussed the same article this month. @hswapnil tweeted a useful chart comparing radiation doses (think about this next time you eat a banana) https://www.xkcd.com/radiation/

Although the conclusions among nephrologists were similar, @uretericbud said it best:

Overall, the consensus seemed to be that the paper presents good evidence for starting with ultrasound in the ED but applying this in all institutions may be difficult. Ultrasound also has limited use for urologists who are focused on stone treatment rather than catastrophic misses. Finally, some concluding thoughts from participants:

Thank you to all the tweeps over the last two years who have provided knowledge, insight, and a healthy dose of comedy to make #urojc such a huge success. Plugging an idea floated by @CanesDavid…

This month’s best tweet prize was sponsored by one beautiful thing vintage furniture.

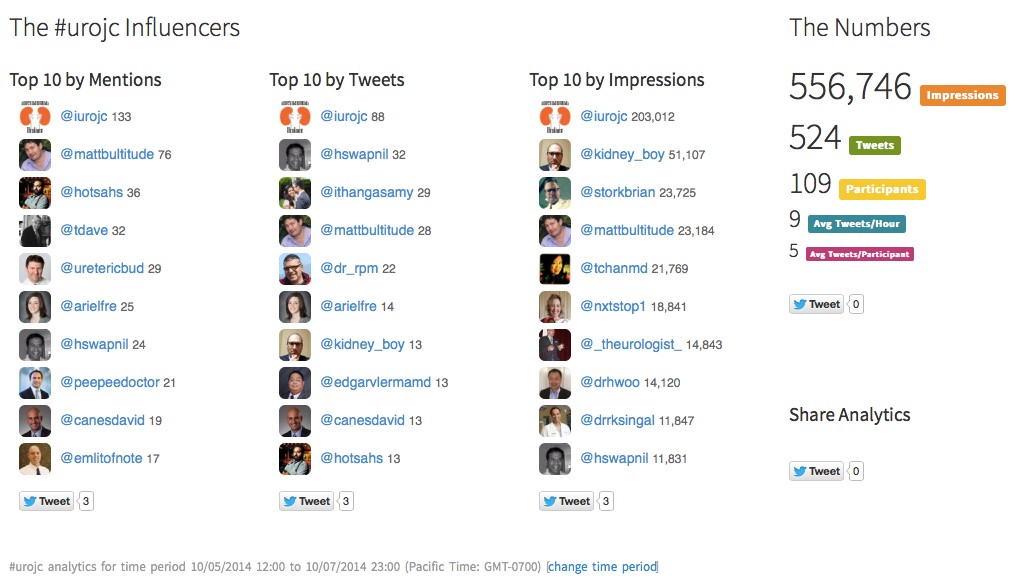

Lastly, here are the symplur analytics for the month.

Ariel Fredrick is a PGY-2 urology resident at Lahey Hospital in Burlington, Massachusetts.

Editorial: Is surgery a never ending learning process?

The concept of the learning curve is one of the most important issues in surgery and also one of the most overlooked. In the present issue of BJUI, Abboudi et al. [1] present an interesting review paper evaluating the concept of the learning curve in urological procedures. Specifically, the authors have conducted a methodologically consistent systematic review on the literature focused on the learning curve of some urological procedures, including mainly radical prostatectomy (RP), robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN) and percutaneous nephrolitotomy [1]. Surprisingly, nothing was available for BPH treatments, which are among the most prevalent urological procedures.

Most of the studies are focused on robot-assisted RP (RARP), but the available literature is of poor methodological quality, including mainly surgical series evaluating a limited number of surgeons, with a heterogeneous selection of outcomes from which to study the learning curve and a focus on short-term outcomes. Conversely, the literature on retropubic RP or laparoscopic RP is of higher quality, including a few very large multi-institutional studies encompassing the performances of several surgeons (reference nos. 24, 26, 29 and 30 in the review) and adopting sophisticated statistical methodology; however, the current interest for these procedures is quite limited, RARP being more commonly preferred. With the above-mentioned limitations in mind, what we have learnt is that RARP operating time plateaus after 50–200 cases, positive surgical margin (PSM) rates after 50–1600 cases, and continence and potency after 200 cases [1]. Such data are only partially in line with the findings of a recent prospective Australian study [2], not included in the present systematic review, which evaluated the learning curve with RARP of a high-volume open surgeon (>3000 retropubic RPs performed before the study beginning). In that study, Thompson et al. [2] demonstrated that performances with RARP surpassed those with retropubic RP after ∼100 cases for sexual function scores and PSM rates in pT2 cancers, whereas ∼150 cases were needed to reach the same target with urinary function scores. Moreover, RARP performances kept on improving, with sexual and urinary scores plateauing after 600–700 and 700–800 cases, respectively. Similarly, with regard to PSMs, it was demonstrated that PSM rates in pT2 and pT3–4 cancers plateaued after 400–500 and 200–300 cases, respectively [2]. Although improvement is likely, it is not clear how much these performances might improve with further extension of the caseload.

Taken together, those data suggest that even with robotic assistance, a high volume of cases is strongly associated withimproving oncological and functional outcomes after RARP. This is not an extraordinarily original concept, but implies that the daVinci platform, by itself, cannot guarantee excellent surgical quality and that the relevance of the surgeon is as high as ever.

Limited data are available on other major robotic procedures, such as RAPN and robot-assisted radical cystectomy (RARC). Specifically, 20–75 cases are thought to be needed to observe a plateau in warm ischemia time (WIT) during RAPN, which is in line with our previous findings demonstrating a continuous decrease in WIT during the first 50 cases [3]. Similarly, 20–30 cases are supposed to be needed to achieve acceptable operating times, lymph node yields and PSM rates after RARC; however, those findings do not take in account the burden of robotic experience achieved with RARP before embarking in RARC, which is clearly a major issue [4].

Considering that the improvements in performances along the learning curve exceeded any effect sizes we might reasonably expect from a novel drug [5], it is clear that any attempt to centralise treatments for complex procedures in high-volume centres with high-volume surgeons should be attempted. Obviously, that is a very critical target, which is hard to achieve in many realities. In parallel, interventions to improve the performance of surgeons in order to,reduce the learning curve are mandatory. For example, fellowship-trained RARP surgeons have been shown to outperform experienced open or laparoscopic surgeons moving to RARP without specific training [6,7]. For those surgeons for whom fellowship is unfeasible or unpractical, structured courses with integration of simulation, dry laboratory, wet laboratory and da Vinci modular training, for example, using the model of the recently concluded European Robotic Urology Society Pilot Study, can significantly ease the first steps of the learning curve, reducing patients risk. In parallel, intensive courses focused on specific procedures could help those surgeons who had completed the initial steps of their learning curve to master the specific technical details necessary to improve outcomes.

Alexander Mottrie*† and Giacomo Novara†‡

*OLV Vattikuti Robotic Surgery Institute and † Department of Urology, OLV Hospital Aalst, Aalst, Belgium and ‡ Department of Surgery, Oncology and Gastroenterology, Urology Clinic University of Padua, Padua, Italy

References

1 Abboudi H, Khan MS, Guru KA et al. Learning curves for urological procedures: a systematic review. BJU Int 2014; 114: 617–29

2 Thompson JE, Egger S, Böhm M et al. Superior quality of life and improved surgical margins are achievable with robotic radical prostatectomy after a long learning curve: a prospective single-surgeon study of 1552 consecutive cases. Eur Urol 2014; 65: 521–31

3 Mottrie A, De Naeyer G, Schatteman P et al. Impact of the learning curve on perioperative outcomes in patients who underwent robotic partial nephrectomy for parenchymal renal tumours. Eur Urol 2010; 58: 127–32

4 Hayn MH, Hellenthal NJ, Hussain A et al. Does previous robot-assisted radical prostatectomy experience affect outcomes at robot-assisted radical cystectomy? Results from the International Robotic Cystectomy Consortium. Urology 2010; 76: 1111–6

5 Vickers AJ. What are the implications of the surgical learning curve? Eur Urol 2014; 65: 532–3

6 Kwon EO, Bautista TC, Jung H et al. Impact of robotic training onsurgical and pathologic outcomes during robot-assisted laparoscopicradical prostatectomy. Urology 2010; 76: 363–8

7 Leroy TJ, Thiel DD, Duchene DA et al. Safety and peri-operative outcomes during learning curve of robot-assisted laparoscopicprostatectomy: a multi-institutional study of fellowship-trainedrobotic surgeons versus experienced open radical prostatectomysurgeons incorporating robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. J Endourol 2010; 24: 1665–9

What’s the Diagnosis?

Test yourself against our experts with our weekly quiz. You can type your answers here if you want to compare with our answers, or just click the ‘submit’ button below.

This image is from a recent paper by Hefermehl et al on lateral temperature spread by different robotic instruments.

No such quiz/survey/pollAre You Teaming Up for Movember?

Urology, Social Media, and Prostate Cancer Controversies

The past couple of years have witnessed a rapid rise in the number of urologists engaging in conversation using social media. Urologists across the globe are now participating in the International Urology Journal Club on Twitter (#UROJC), tweeting at conferences, and using social media to build personal and professional relationships. As a result, providers with a passion for men’s health, who may never previously met in real life, are sharing ideas and experience with respect to issues in urology and patient care.

The past couple of years have witnessed a rapid rise in the number of urologists engaging in conversation using social media. Urologists across the globe are now participating in the International Urology Journal Club on Twitter (#UROJC), tweeting at conferences, and using social media to build personal and professional relationships. As a result, providers with a passion for men’s health, who may never previously met in real life, are sharing ideas and experience with respect to issues in urology and patient care.

This uptick in the use of social media comes at a time when when prostate cancer screening and the optimal care of the prostate cancer patient are being hotly debated. More research is clearly needed to settle many of the debates currently taking place both in traditional media and on social media. It, therefore, makes sense for the global urology community to partner with organizations that have a similar passion for advancing and promoting men’s health through scientific research.

Movember – Raising Awareness and Funding for Men’s Health Initiatives

Movember is a movement that began in Melbourne, Australia, in 2003. Since that time, it has spread to more than 20 other countries around the world. Each November, participants raise awareness and money for men’s health by growing a moustache. As the month goes on, and the mustache takes shape, these men become walking and talking men’s health billboards. Participants use their mustache to facilitate conversations about a wide variety of men’s health issues including prostate cancer, testicular cancer, and men’s mental health. They also actively raise money for the Movember Foundation by asking family and friends to donate to their efforts.

Movember is not just for men. Women (Mo Sistas), through encouragement, conversation, fundraising, and, in some cases, sheer tolerance, are a critical part of Movember’s success. Mo Sistas do everything Mo Bros do – they just don’t grow a moustache. Since Movember started, more than 4 million Mo Bros and Mo Sistas around the world have participated. In the process over $556 million dollars has been raised for the Movember Foundation.

Funding Cancer Research in Urology

Since its very inception, the Movember Foundation has supported ongoing research in men’s health. Currently the Movember Foundation is funding more than 832 men’s health programs worldwide. In 2010, Movember created a Global Action Plan to improve the clinical tests and treatments used for men with prostate and testicular cancer. Currently, Movember is funding prostate cancer research in four areas:

1. Developing more accurate blood, urine and tissue tests to differentiate between low risk and aggressive forms of prostate cancer.

2. Developing new imaging techniques that enable the earlier detection of metastatic prostate cancer.

3. Optimizing the management of men with low risk prostate cancer.

4. Understanding how increasing physical activity might improve the quality of life and survival of prostate cancer patients.

Movember’s criteria for research support encourages national and international collaboration. Working collaboratively, research groups are able to pool experience, streamline cost, and avoid duplication, in an effort to accelerate the bench-to-bedside development of new investigations and treatments.

Disrupting the Status Quo

In the past, many different men’s health initiatives have come and gone. Movember’s innovative approach is unique in that each year, for a full month, the movement puts important men’s health issues – such as prostate cancer, testicular cancer and men’s mental health – back into the public spotlight. The effect of the movement has been to not only energize men, but also healthcare, and even government.

One great example of this is the Prostate Cancer of Australia Specialist Nurse Program. The program, initially funded by Movember in 2011 with AU $3.6m, placed full time specialty nurses in every Australian state to help fill a gap in prostate cancer support and delivery. The pilot program was so successful that the Australian government invested AU $7.2m to allow the program to further expand. Movember has also created a variety of unexpected domino effects in the men’s health community. This year, our American colleagues, Dr. Jamin Brahmbhatt and Dr. Sijo Parekattil, inspired in part by the success of the Movember movement, started the Drive for Men’s Health. There are likely many others who, if asked, would tip their hats in the direction of Movember for their inspiration.

When Urologists Participate, Patients Benefit

Urologists by their very nature are both competitive and cooperative. The Movember movement is a unique opportunity for urologists across continents to join with other individuals and organizations that are passionate about improving the health and quality of life of men. Movember is also an opportunity for colleagues, who may have only met via social media, to cooperate and/or compete all in an effort to raise awareness and money for men’s health research. Last year, for example, Canadian urologist Dr. Rajiv Singal, assembled an international Movember team of Canadian and American urologists, patient advocates, and other healthcare providers to raise money and awareness for men’s health. Working together, the team raised nearly CA $50,000 dollars for the Movember Foundation.

An Invitation to Team Up

In the spirit of collaboration and friendly competition, this November we invite our urology colleagues from around the world to start their own local Movember Team, or to join our international team as we attempt to better our fundraising performance from last year.

Editorial: Patient-reported outcomes – a force for clinical improvement or another way for ‘big brother’ to survey clinicians?

In the 19th century Lord Kelvin wrote, ‘If you cannot measure it, you cannot improve it’. Since then clinical improvement has often been about measuring outcomes to determine what elements of healthcare are working well and what can be improved. The early studies of antisepsis and surgical technique had endpoints, which were measured by doctors deciding whether a wound infection, cancer recurrence or even death had occurred. These outcomes were usually discrete with little room for describing states between success and failure.

In this era whether the patient perceived that the treatment had been successful or not was irrelevant to the ‘success’ of treatment providing that the medical world agreed that the treatment had been a success. As treatments have become more established and the medical and pharmaceutical world has become more patient focussed, interest has increased in how patients report the outcome of treatment, often using questionnaires.

The pioneers of this work were mainly psychiatrists concerned about patient anxiety and depression [1] and clinical oncologists, aware that multimodal chemoradiotherapy treatments, which might in many cases be offered with palliative rather than curative intent, had the potential to cause a net loss in quality of life even if patients lived a short time longer on treatment.

As these patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) became more commonly used in clinical trials, their focus has extended to quite specific outcomes, such that in the current era it is unusual to see papers on LUTS or erectile function presented that do not use validated PROMs, such as the IPSS [2] or International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) [3].

The current era of research is starting to make new use of the data sources that are useful both as absolute values relating to the severity of symptoms but also particularly in measuring change in level of symptoms. Hard outcomes, such as death from cancer, have been found to be related to patient reported quality of life at presentation [4].

Clinicians are now starting to develop the necessary skills to analyse PROMs. In this setting Talcott et al. [5] have used PROM data to identify unexpected variances in symptomatic outcome after prostate brachytherapy. This was an unexpected post hoc analysis of a difference in outcomes between the two control groups in a study. It found that there was a significant difference in outcome between patients who had received an implant in two centres, which might have been expected to have similar outcomes. Analysis of differences in the implant technique in the two institutions suggested that the use of a urethral catheter to clearly visualise the urethra might be the difference and modification of this part of the technique resulted in similar PROMS outcomes in both institutions.

This is a novel quality improvement approach, which may become more widespread as institutions more frequently collect, analyse and present their PROMS. The bio-informatics skills needed to analyse this type of data meaningfully may become a greater part of everyday practice in the modern era, especially for the ‘index’ most common operations in surgical specialities. It would be interesting to see what a similar approach would produce if variance in PROMs after transurethral prostate surgery were analysed between centres in the UK and USA. Organisations with a track record for effective data analysis and reporting such as Dr Foster will be watching this evolve.

Alastair Henderson

Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust, Department of Urology, Maidstone Hospital, Maidstone, Kent, UK

References

1 Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiat Scand 1983; 67: 361–70

2 Barry MJ, O’Leary MP. Advances in benign prostatic hyperplasia. The developmental and clinical utility of symptom scores. Urol Clin North Am 1995; 22: 299–307

3 Cappelleri JC, Rosen RC, Smith MD, Mishra A, Osterloh IH. Diagnostic evaluation of the erectile function domain of the International Index of Erectile Function. Urology 1999; 54: 346–51

4 Montazeri A. Quality of life data as prognostic indicators of survival in cancer patients: an overview of the literature from 1982 to 2008. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009; 7: 102

5 Talcott JA, Manola J, Chen RC et al. Using patient-reported outcomes to assess and improve prostate cancer brachytherapy. BJU Int 2014; 114: 511–6

What’s the diagnosis?

Test yourself against our experts with our weekly quiz. You can type your answers here if you want to compare with our answers, or just click the ‘submit’ button below.

Image from Alei et al. BJUI 2014

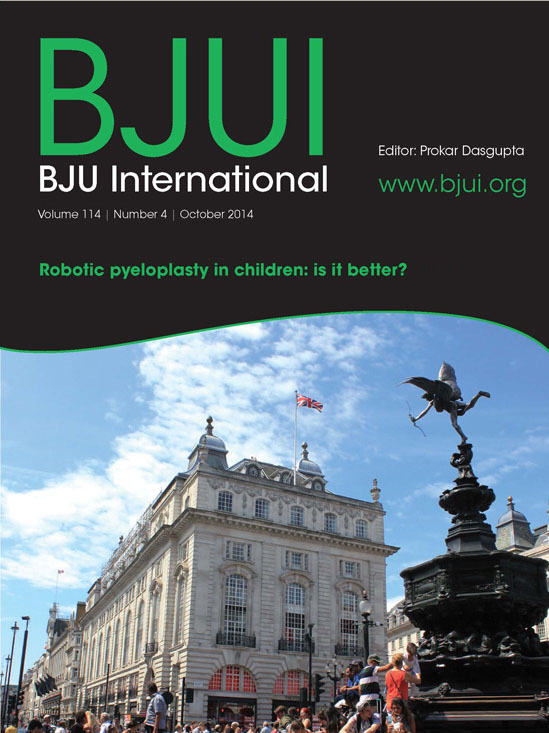

No such quiz/survey/pollEditorial: Robot-assisted pyeloplasty in children

The authors of the study on robot-assisted pyeloplasty in this issue of BJUI have carried out an excellent review of the current data on this common paediatric urology procedure [1]. Although the analysis involves small case numbers and series for meta-analysis, the data are useful for current practice. It may be worth waiting another 5 years to review the data again, by which time the learning curve for most of the surgeons will be over, and a true representation of practice and a comparison against the established standard open surgery, which has been established over decades, can be reported. The training of next-generation surgeons needs to be factored into this process, which is critically important.

With the different methods of critical evaluation presently available, we may be able to draw some conclusions from the results of robot-assisted pyeloplasty, but the problem that remains is the inconsistency of individual reports in terms of outcome and complications. We surgeons need to work on developing a consensus model for the evaluation of each procedure so that uniformity exists. The financial implications of new technology will always be higher than expected, but with a greater number of users and competitive producers the cost will be remarkably reduced. As paediatric surgeons, we do not know the unseen benefits of robot-assisted pyeloplasty, but the children’s families have a positive perception of post-surgical aesthetic appearance, and may also have some human capital gains in terms of reduced childcare expenditure. The paradigm shift to a digital era of surgery is here to stay, with safety and refinements to technology being universally available to all children.

Mohan S. Gundeti

BJUI Consulting Editor, Paediatrics, The Medicine University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

References

1. Cundy TP, Harling L, Hughes-Hallett A et al. Meta analysis of robot-assisted vs conventional laparoscopic and open pyeloplasty in children. BJU Int 2014; 114: 582–94