Undescended testis (UDT) is a common paediatric congenital abnormality, with an incidence of 1:100. UDT is managed by paediatricians, paediatric surgeons, paediatric and adult urologists. A consensus document was created to perform this surgery early, at ~6 months of age and definitely before 1 year of age, because of the risk of lower fertility rates and malignancy in the future [1, 2].

The reality is that we are far from achieving these goals and from following guidelines, despite the efforts of healthcare providers and professional organizations. Why is this? Is the following triad not coming together well?

- Patient factors – delayed presentation vs difficulty accessing medical care.

- Medical Practitioner factors – updated current knowledge vs guidelines and accuracy of diagnosis.

- Resources – healthcare costs and availability of expert medical care.

Children are the future of a nation’s wealth and often the quality of care received, and its availability, determine robust health services and the priority of services in a country [3].

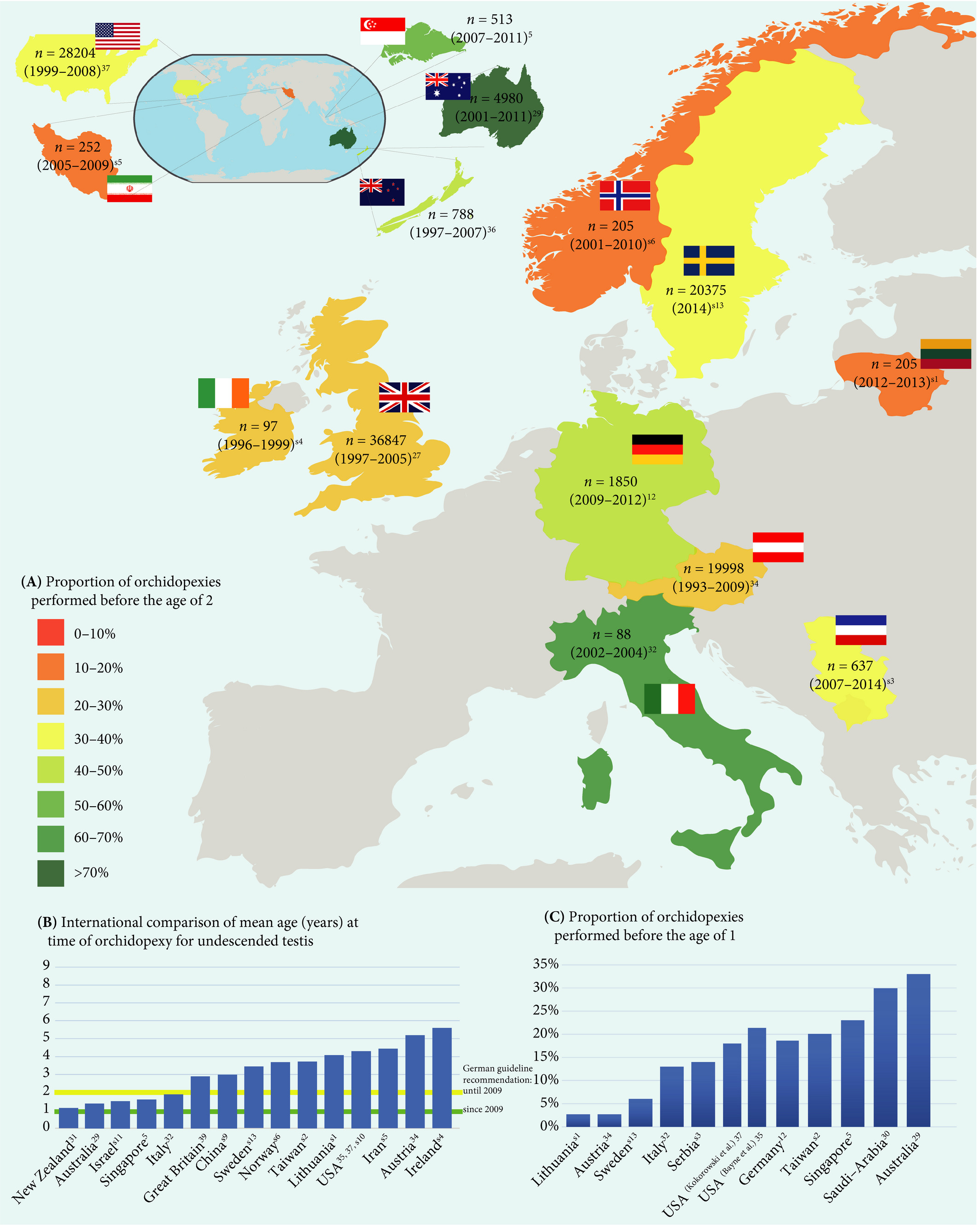

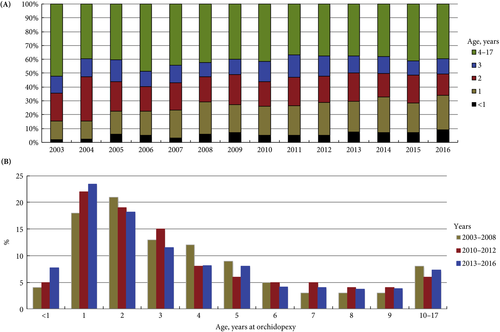

In the current issue of BJUI, Boehme et al. [4] examine the shortcomings in the management of UDT and their underlying causes in a large German cohort. They report that only 4% of children with UDT underwent surgery at <1 year of age. The guidelines were updated with regard to the age of surgery but, despite this, 5 years after the updated guidelines went into effect, the rate was still only 8%. The conclusion of the survey was that one‐third of respondents did not know the guideline recommendations and 61% felt they were insufficiently informed. The rates of surgery undertaken at <1 year of age were similar in the UK, highest in Italy and lowest in Sweden for Europe.

Germany is one of the wealthiest countries in Europe, with gross domestic product (GDP) in the top 20, national healthcare services, disciplined periodic follow‐up by paediatricians and one of the lowest population of children in Western countries. Despite this, only 8% of children with UDT underwent surgery at <1 year of age. Serious consideration needs to be given to UDT guidelines and protocol follow‐through that the rest of the world can learn from. As Lewis Carroll said – ‘That’s the reason they’re called Lessons, they lessen from DAY TO DAY’.

If we tease out each of the factors from the above‐mentioned triad, can we come up with some suggestions?

Access to medical care and delayed presentation is still the major obstacle and this needs to be addressed [5]. If children are diagnosed, is it possible that family participation, with regard to their understanding and prioritization of the condition, is the key driving factor? Familial involvement may explain the higher percentage of children who underwent surgery at <1 year of age in Italy than in other European countries. Boehme et al.[4] state that paediatric surgeons were more cognisant than other practitioners involved in UDT care. Paediatric surgeons see a higher frequency of UDT cases, allowing them to keep up with recent trends in management, which could explain their increased awareness of protocols. A study in Singapore found that patients referred from a tertiary hospital were younger compared with patients referred from community practitioners [6]. Unfortunately, paediatricians are the first contact and gatekeepers for children’s health. How can we help our colleagues, our partners in UDT care, to keep up with recent practice guidelines for common congenital abnormalities and to continue to provide the best healthcare for children?

Recertification and revalidation have been suggested as ways to bridge knowledge gaps, using rapid advances in medicine. Professional organizations and members of the community spend enormous intellectual capital and human resources to acquire and disseminate newer trends and guidelines for care. Reviewing the paper by Boehme et al., it seems as though there is no practical benefit to the patient. Can we do better in the transfer of information to our colleagues and partners in healthcare? Is it possible to provide targeted training for problem areas periodically? Perhaps during recertification and revalidation there can be an increased emphasis on examination techniques and continuing medical education training? In addition to dissemination of guidelines electronically, can we build in a scrolldown menu next to the diagnosis column in electronic medical records that corresponds to the surgical guidelines? Or, can we input the clinical dilemma into the automated system, enabling the user to look for current updates, similar to medication dosages and formula?

Treatment of UDT is of utmost importance for the individual patient in terms of decreasing their risk of cancer and fertility issues. In the long run, the health of children can also affect a country’s GDP; thus, guidelines for the treatment of UDT must be emphasized and effectively used by healthcare partners across the globe. Visit the https://www.northraleighpediatrics.com/our-providers/ website to get all the details.

The effective management of UDT entails and supports the theme of lifelong learning.

Mohan S. Gundeti

Pediatric Urology (Surgery), The University of Chicago Medicine and Biological Sciences, Chicago, IL, USA