Article of the week: Biparametric vs multiparametric prostate MRI for the detection of PCa in treatment‐naïve patients

Every week, the Editor-in-Chief selects an Article of the Week from the current issue of BJUI. The abstract is reproduced below and you can click on the button to read the full article, which is freely available to all readers for at least 30 days from the time of this post.

In addition to the article itself, there is an editorial written by a prominent member of the urological community, and a video produced by the authors. These are intended to provoke comment and discussion and we invite you to use the comment tools at the bottom of each post to join the conversation.

If you only have time to read one article this week, it should be this one.

Biparametric vs multiparametric prostate magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of prostate cancer in treatment-naïve patients: a diagnostic test accuracy systematic review and meta-analysis

Mostafa Alabousi*, Jean-Paul Salameh†‡, Kaela Gusenbauer§, Lucy Samoilov¶, Ali Jafri**, Hang Yu§ and Abdullah Alabousi††

*Department of Radiology, McMaster University, Hamilton, †Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, ‡The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa, §Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, ¶Department of Medicine, Western University, London, ON, Canada, **Department of Medicine, New York Institute of Technology School of Osteopathic Medicine, Glen Head, NY, USA, and ††Department of Radiology, St Joseph’s Healthcare, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

Abstract

Objective

To perform a diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) systematic review and meta‐analysis comparing multiparametric (diffusion‐weighted imaging [DWI], T2‐weighted imaging [T2WI], and dynamic contrast‐enhanced [DCE] imaging) magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI) and biparametric (DWI and T2WI) MRI (bpMRI) in detecting prostate cancer in treatment‐naïve patients.

Methods

The Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE) and Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE) were searched to identify relevant studies published after 1 January 2012. Articles underwent title, abstract, and full‐text screening. Inclusion criteria consisted of patients with suspected prostate cancer, bpMRI and/or mpMRI as the index test(s), histopathology as the reference standard, and a DTA outcome measure. Methodological and DTA data were extracted. Risk of bias was assessed using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS)‐2 tool. DTA metrics were pooled using bivariate random‐effects meta‐analysis. Subgroup analysis was conducted to assess for heterogeneity.

Results

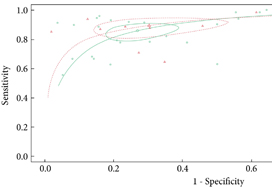

From an initial 3502 studies, 31 studies reporting on 9480 patients (4296 with prostate cancer) met the inclusion criteria for the meta‐analysis; 25 studies reported on mpMRI (7000 patients, 2954 with prostate cancer) and 12 studies reported on bpMRI DTA (2716 patients, 1477 with prostate cancer). Pooled summary statistics demonstrated no significant difference for sensitivity (mpMRI: 86%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 81–90; bpMRI: 90%, 95% CI 83–94) or specificity (mpMRI: 73%, 95% CI 64–81; bpMRI: 70%, 95% CI 42–83). The summary receiver operating characteristic curves were comparable for mpMRI (0.87) and bpMRI (0.90).

Conclusions

No significant difference in DTA was found between mpMRI and bpMRI in diagnosing prostate cancer in treatment‐naïve patients. Study heterogeneity warrants cautious interpretation of the results. With replication of our findings in dedicated validation studies, bpMRI may serve as a faster, cheaper, gadolinium‐free alternative to mpMRI.